Like many other Americans interested in the Middle East, I became aware of Thomas L. Friedman during the long, difficult summer of 1982. Not only did his reporting from Beirut for The New York Times stand out by virtue of its objectivity, but it had a sparkle and an insight lacking in other dispatches from that city; his stories explained the news at the same time that they reported it. Subsequent events made clear that I was not the only one to take notice of Friedman. He went on to earn fame and prizes for his reporting from the Middle East, and he has recently moved to Washington as the Times' chief diplomatic correspondent.

Between assignments, Friedman gathered up his observations of the Middle East into From Beirut to Jerusalem, a book whose title exactly sums up its contents, being evenly divided between "Beirut" (where he lived most of the time between mid-1979 and mid-1984) and "Jerusalem" (1984-88). The book is every bit as good as the newspaper pieces; indeed, it is a model for a journalist's account, weaving together theme and anecdote with deftness and skill.

Between assignments, Friedman gathered up his observations of the Middle East into From Beirut to Jerusalem, a book whose title exactly sums up its contents, being evenly divided between "Beirut" (where he lived most of the time between mid-1979 and mid-1984) and "Jerusalem" (1984-88). The book is every bit as good as the newspaper pieces; indeed, it is a model for a journalist's account, weaving together theme and anecdote with deftness and skill.

Friedman explains daily life in Lebanon during civil war in a way that helps makes sense of that bizarre existence for anyone who has not spent time there. His vignettes neatly capture the contradictions of an existence in which, because fighting takes place in only some places and at only some times, passers-by on one street will witness a raging gun battle while shoppers browse around the corner. After a car bombing in Beirut, the most frequently asked question is not "Who did it?" or "How many were killed?" but "What did it do to the dollar rate?" Likewise, "How is it outside?" refers not to the weather but to the security situation. Much as American radio stations offer information on the traffic, Lebanese radio stations compete for market share by providing the most timely and complete information on street conditions. One anecdote concerns a dinner party Friedman attended on Christmas Eve 1983. The apartment was rocked by artillery salvos, so the hostess put off dinner in the hope that things would settle down. But, seeing that her friends were getting hungry, not to mention nervous, "finally, in an overture you won't find in Emily Post's book of etiquette, she turned to her guests and asked, 'Would you like to eat now or wait for the ceasefire?'"

Not unreasonably, Friedman is pessimistic about Lebanon. His view of the country's prospects is summed up by a psychologist at the American University of Beirut whom he quotes as saying that peace will come "when the Lebanese start to love their children more than they hate each other."

Surprisingly, Friedman is nearly as pessimistic about Israel, a country whose deep internal divisions, he writes, must constantly be papered over anew for normal political life to go on. With a touch of hyperbole, Friedman foresees the possibility of Israel going the way of Lebanon. "If forced to confront the real and passionate ideological differences in their country ... [Israelis] could end up like the Lebanese: arguing first in the parliament and then in the streets. To put it bluntly, asking an Israeli leader to really face the question, 'What is Israel?' is like inviting him to a civil war."

In the Jerusalem half of his book, Friedman naturally devotes considerable attention to the conflict between Israelis and Palestinians. Here too he is deeply pessimistic, portraying the contest as a brutal war for communal survival.

One side had knives and pistols; the other had secret agents and courts. While each constantly cried out to the world how evil the other was, when they looked one another in the eye - whether in the interrogator's room or before inserting a knife in a back alley - they said something different: I will do whatever I have to survive. Have no doubt about it.

This frightful picture notwithstanding, Friedman proposes innovative guidelines for a solution. "The Palestinians must make themselves so indigestible to Israelis that they want to disgorge them into their own state, while at the same time reassuring the Israelis that they can disgorge them without committing suicide." To accomplish this nearly impossible task, Palestinians, in Friedman's view, have to adopt a two-pronged tactic, combining "the stick of non-lethal civil disobedience and the carrot of explicit recognition." It is worth pointing out that although Friedman is highly critical of the Israelis, his proposal implies that Palestinians undertake virtually all the initiatives, and until they do, he does not blame Israelis for skepticism.

Short of the Palestinians taking up the two-sided tactic of civil disobedience and explicit recognition, Friedman foresees no real change in the status quo. Although he calls the intifada an "earthquake," he cannot imagine it solving the basic impasse:

Israelis will be interested in hearing what Arafat and the Palestinians have to say as a nation only when the Israelis feel that they have no choice but to make a deal with the Palestinians as another nation on the land. A person is interested in the terms of a deal only when he feels he has to make a deal. The intifada has not ... exerted enough internal pressure on Israelis, or offered them enough incentives, to convince a significant majority that they can and should share either power or sovereignty.

One of Friedman's strong points as a writer is his ability to convey complex problems simply and pungently. His expression "Hama rules" (referring to the Syrian city's destruction by the Asad government) has entered the vocabulary. His aphorism, "Middle East diplomacy is a contact sport," is quoted on occasion. Not bad, either, is his dubbing of the Commodore, the West Beirut hotel that once served as base for Western journalists, "an island of insanity in a sea of madness." Here, using the imagery of a couple falling in love and learning about each other's families, he explains the process of mutual discovery between American Jews and Israelis during the mid-1970s:

American Jews suddenly found themselves exclaiming to Israelis, "Hey, I fell in love with Golda Meir. You mean to tell me that Rabbi Meir Kahane is in your family! I went out with Moshe Dayan - you mean to tell me that ultra-orthodox are in your family! I loved someone who makes deserts green, not someone who breaks Palestinians' bones." Israelis eventually found themselves equally aghast and exclaiming, "Look, American Jew, just because we are dating doesn't mean you can tell me how to live my life. And anyway, American Jew, if we are in love, then you should move in with me."

But if Friedman excels at the journalistic insight and the apt quote, he is in the final analysis unable to transcend the limits of his craft. His proximity to the scene of action means he gets the larger context wrong. Thus, his assertion that "the PLO under Yasir Arafat was the first truly independent Palestinian national movement" ignores twenty years of the Arab High Committee under Amin al-Husayni. Explaining Ayatollah Khomeini's anti-Americanism as a function of his "grudge" against Americans support for the shah is a woefully inadequate reading of Khomeini's ambition to spread an ideology of radical Islam. And the style sometimes degenerates, such as the infelicitous observation that "every reporter in Beirut was fully aware that for $1.98 and ten green stamps anyone could have you killed."

The same superficiality extends to Friedman's treatment of the Arab-Israeli conflict. Even though the Arab states' hostility toward Israel remains the heart of the Arab-Israeli problem, there is hardly a word about it in From Beirut to Jerusalem, which suggests that the Arab-Israeli conflict is nothing more than a bilateral confrontation between Palestinians and Israelis. Friedman's exceedingly narrow vision may reflect the fact that the Palestinians are more prominent in the daily news coming out of Israel; but a book needs to be more than a compilation of news dispatches. His implication that the communal contest is the real problem reveals a shallow understand of eight decades of Arab-Israeli strife.

Finally, the author's highly emotional relationship with Israel biases his views of that country. Friedman confesses having grown up thinking of Israel in mythic, heroic terms; he then charts the progress of his disenchantment, the final stage of which occurred in September 1982, at the time of the Sabra and Shatila massacre. When official Israel obfuscated about the role played by Israeli armed forces in permitting the massacre of Palestinian Muslim Arabs by Lebanese Christian militiamen, a grievously disappointed Friedman "buried ... every illusion" he ever held about the Jewish state.

Actually, however, Friedman continued to be haunted by what he calls illusions, and he still labors under their sway. Their effects can be traced in the intense mix of affection and anger that suffuses his writing about Israel, so unlike his Olympian reports from Lebanon. When, for example, he refers heatedly to "Jewish power, Jewish generals, Jewish tanks, Jewish pride" as Menachem Begin's pornography, he may be revealing more about his own fantasy life than Begin's. He still feels tied to Israel, and therefore in some inchoate way responsible for what Israelis do. Friedman on Israel resembles an anthropologist who studies his disowned family.

Writing in 1987, my colleague Adam Garfinkle observed that "the new tradition of The New York Times' foreign correspondents writing long, anecdotal, and lyrically styled books on the subject of their most recent assignments" has filled the niche once held by nineteenth-century travelogues. Both genres emphasize first-hand experience; both serve as adjuncts to scholarly literature; and both offer severe reductions of complex political and cultural realities. Thomas Friedman has produced one of the better of this unusually blighted form, even if he does not transcend his journalistic roots.

In some part, this has to do with his academic background in Middle East studies plus command of both the Arabic and Hebrew languages. The more the pity, then, that Friedman no longer brings his special skills to cover the Middle East. Like virtually every other large institution in the United States, The New York Times ceaselessly moves its employees from one assignment to another. Unlike European newspapers (such as Le Monde or the Financial Times), American ones condemn themselves - and their readers - to reportage by journalists who are ever learning their beat. As this book is likely to be Friedman's last writing on the Middle East for a while, it is to be savored.

From Brandeis to Jerusalem

Letter to the Editor

Commentary

January 1990

pp. 12-15

TO THE EDITOR OF COMMENTARY:

In his review of Thomas Friedman's From Beirut to Jerusalem, Daniel Pipes properly chastises Friedman for his superficial, even misguided, illusions about Israel [Books in Review, September 1989]. But beneath these apparently innocent "illusions" is the autobiographical myth of Thomas Friedman. Abetted by credulous colleagues, who have swallowed his autobiographical pronouncements whole, Friedman has created a myth of personal disillusionment with Israel that is designed to lend credibility to his indictment of the Jewish state and, not incidentally, to conceal its ideological sources.

As Friedman writes, and frequently reiterates, his is the story of "a Jew who was raised on ... all the myths about Israel, who goes to Jerusalem in the 1980's and discovers that it isn't the summer camp of his youth." Gullible interviewers have embellished the tale. One of them, breathlessly anticipating Friedman's third Pulitzer Prize, listened deferentially to Friedman recount his "much deeper identification with Israel" after the Six-Day War, as the Jewish state became "a symbol of my own identity." Friedman's faith in Israel's moral rectitude endured, he claimed, until his "experiences as a reporter" in the Middle East finally undermined it fifteen years later. Then, according to another interviewer who was fascinated by his lost "illusion," Friedman experienced "a remarkable transformation," indeed "a personal crisis." He watched "an Israel he had deeply believed in while in high school and college recede from gilded, heroic mythology to the shadows of bleak reality."

In fact, Friedman has invented at least the timing of his conversion story, while remaining silent about the indisputable evidence of his own political bias that long antedated his journalistic career. If he actually did plunge into a Gethsemane of crisis and transformation, it occurred well before he went to the Middle East as a reporter. Friedman's adolescent infatuation with Israel was distinguished by its brevity (although Daniel Pipes accurately detects traces of it still). By the time Friedman graduated from Brandeis University in 1975, he was already expressing sympathy with the Palestinian national cause, offering apologies for PLO terrorism, and identifying with Breira, the single organization so reflexively critical of Israel that it quickly became a pariah group within the American Jewish community.

During his final year at Brandeis, after returning from a summer of study in Cairo, Friedman belonged to the steering committee of a self-styled "Middle East Peace Group." It vigorously opposed the mounting storm of protest among American Jews (to be expressed in a "Rally Against Terror") over Yasir Arafat's impending appearance before the United Nations General' Assembly. In November 1974, on the day before Arafat's infamous declaration that Zionism is racism, delivered while brandishing a pistol on his hip, the Peace Group published a statement in the Brandeis Justice. Co-signed by Friedman, it called for Israel to negotiate with "all factions of the Palestinians, including the PLO" and stated that the issue of "Palestinian self-determination," a standard euphemism for a Palestinian state, was "one of the central issues blocking peace in the Middle East."

The statement acknowledged repeated acts of PLO terror against Jews, but claimed they were "clearly not representative of the diverse elements of the Palestinian people," though the only evidence of such diversity presented was of those even more committed to terrorism than the PLO itself. It also asserted that "international condemnation of terrorist activities for which the PLO is responsible can have little effect. ..." The group joined Breira, already notorious for its endorsement of Palestinian goals and for the blame it placed on the United States and Israel for Middle East instability, in urging "a more meaningful and constructive approach" than protesting against Arafat and the PLO.

The Middle East Peace Group continued to profess its "concern" for Israel by criticizing American "military and political elites" for reinforcing the strategic alliance with Israel. Among all the impediments to peace in the Middle East, not the least of which was the unrelenting Arab hostility to Israel expressed exactly one year earlier in the Yom Kippur War, the group could only locate the "dangers of U.S. power as a tool for forging peace."

As a journalist in Lebanon, Friedman writes, he experienced "something of a personal crisis. ... The Israel I met on the outskirts of Beirut was not the heroic Israel I had been taught to identify with." Outraged, and determined "to nail Begin and Sharon" (a curious role for a reporter), Friedman wrote the article that won his first Pulitzer. A week later, he "buried" the Israeli commanding officer on page one of the New York Times, and "along with him every illusion I ever held about the Jewish state." That surely qualified him for his assignment to Israel; furthermore, his editor wanted, in part, "to dispense with an old unwritten rule ... of never allowing a Jew to report from Jerusalem."

Thus the myth of Thomas Friedman was born, to be nurtured after publication to propel his book up the best-seller list. His "personal crisis" of disillusionment with "heroic" Israel, by now a well-worked theme of leftist critics, was calculated to lend credibility to his updated version of Middle East Peace Group position papers. The confession of a conversion experience, after all, is far more compelling than the more mundane, if more accurate, revelation that Friedman the journalist was still following the old Breira party line.

Freedom of association, of course, is a constitutional right, which Friedman, no less than any other American, enjoys. But full disclosure of a consistent ideological bias, sustained over fifteen years, might be considered a minimal gesture of journalistic integrity. Friedman concedes—for he could hardly do otherwise—that he was "not professionally detached" when he wrote his prize-winning articles after Sabra and Shatila. But his self-serving claim that his outrage at Israel "made me a better reporter" is a preposterous assertion, which has yet to receive critical scrutiny from within his own profession.

Friedman, moreover, has virtually disqualified himself, in public, as even a remotely objective analyst. Back in 1985, after the Shiite hijacking of the TWA airliner, he vigorously attacked Israel (on Israeli radio) for not releasing the 700 terrorists whose freedom the hijackers were demanding. Israel's refusal, he claimed, "certainly contributed" to the hijacking (as, certainly, a victim's body contributes to rape or homicide). Again in 1989, after Israel's capture of the terrorist Sheik Obeid in Lebanon, followed by the grisly home movie of the hanging of Colonel Higgins, Friedman declared on Nightline that "both sides [sic] have really used Higgins and exploited him in a very tragic way." For sheer vulgarity, such characterizations of Israel are exceeded only by Friedman's own description of the Jewish state, in his book, as "Yad Vashem with an air force."

As for the "old unwritten rule" at the Times about not sending a Jew to Jerusalem, that, too, is a myth. During the 1929 Arab riots in Palestine, the slaughter of more than 100 Jews in Hebron and Jerusalem produced a stream of Times articles as hostile to the Zionists as they were indifferent to the Jewish victims. The correspondent who wrote them was Joseph Levy, ... an American Jew, conversant in Arabic and Hebrew, who had spent years in Beirut before coming to Jerusalem, where he wrote for the Times, conceding that if his efforts toppled the Zionist administration in power, so much the better. ... But who remembers Joseph Levy?

As for Thomas Friedman, in reality if not mythology, he has followed the same ideological path that he chose as an undergraduate. ...

Incidentally, a mere two weeks after the New Republic published a brief letter from me about Friedman's undergraduate enthusiasm for the Palestinian cause, the magazine took the almost unheard-of step of apologizing for having done so, claiming I had distorted the statement Friedman signed in 1974. To the contrary: I accurately represented his position and I have challenged the editors of the New Republic to print the 1974 text in full so that readers may decide for themselves. I have also invited them to acknowledge that the letter for which they apologized was solicited by the editor-in-chief, with advance knowledge of its contents and the supporting evidence.

Jerold S. Auerbach

Wellesley College

Wellesley, Massachusetts

Daniel Pipes writes:

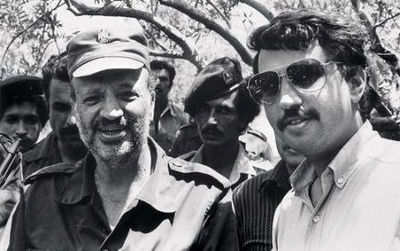

Friedman and Arafat, about the time of the former's professed disillusion with Israel. |

The timing of his disillusion is critical to Friedman's story. Coming at the nadir of Israel's international standing, and when the author was an eyewitness to atrocities, it validates his credentials among those who yet share his once-friendly feelings for Israel. Take away the drama of this disenchantment and Friedman becomes just another writer with an anti-Israel bent, though an unusually talented one.

As Friedman is a highly reputed journalist holding positions of great responsibility, it simply never occurred to me to doubt his autobiographical account. Further, I have talked with Friedman several times and he always struck me as trustworthy.

But Jerold S. Auerbach provides compelling evidence to establish that there is something disingenuous about Friedman's professed Zionism in the late 1970's. It appears that the disillusion he claims for himself in September 1982 took place long before he began reporting from the Middle East.

Mr. Auerbach uses the word "myth" to describe Friedman's rewriting of his past. But his evidence raises the question of whether Friedman has been guilty not of an innocent myth but of a significant deception.

A rewriting of one's own biography has devastating implications for anyone's integrity. It has even greater weight when perpetrated by a journalist—a writer who provides no footnotes and who nearly always has to be taken at his word.

The charges against Friedman call for an answer from him. Specifically, is it true that—as a member of the Middle East Peace Group, of Breira, and as a co-signer of a statement in the Brandeis Justice—he adopted his current highly critical attitudes toward Israel in the early 1970's? If so, how does he account for the claim that he lost faith in Israel only during 1982?

In the absence of a satisfactory answer to these questions, readers are forced to reconsider Thomas Friedman's continued credibility as a correspondent.

Feb. 14, 2001 update: Friedman stayed on the Middle East beat long after this book came out and I offer a decidedly more negative view of his understanding of the region today at "The education of Thomas Friedman."

May 16, 2006 update: For a light whack at the hapless columnist, see my "Humor: Thomas Friedman's Iraq Predictions."

Dec. 13, 2011 update: Friedman wrote a frankly anti-Israel and even antisemitic column today, "Newt, Mitt, Bibi and Vladimir" that has aroused much ire among his usual fans. In the article is this memorable Walt-Mearsheimer-style passage: "I sure hope that Israel's prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, understands that the standing ovation he got in Congress this year was not for his politics. That ovation was bought and paid for by the Israel lobby." Auerbach and I were onto Friedman over two decades ago; good to see the rest of the world catch up.

Dec. 20, 2011 update: The crescendo of criticism prompted Friedman to walk back a bit on his Dec. 13 column: "In retrospect I probably should have used a more precise term like 'engineered' by the Israel lobby — a term that does not suggest grand conspiracy theories that I don't subscribe to. It would have helped people focus on my argument, which I stand by 100 percent."

Dec. 21, 2011 update: Jonathan S. Tobin dispatches Friedman's little adjustment:

this weasel-worded attempt at walking back his brief foray into anti-Semitism shouldn't convince anyone. There is no real difference between "engineered" and "bought and paid for." Both terms seek to describe the across-the-board bi-partisan support for Israel that the ovations Netanyahu received as the result of Jewish manipulation, not a genuine and accurate reflection of American public opinion.

Tobin speculates at Friedman's motives: "What really ticks Friedman off is Israel's decision to ignore his advice. That is something the Times columnist cannot abide. While he may not wish to see it destroyed, he clearly believes it should be punished for its temerity."

Feb. 7, 2012 update: Friedman continues to write about the Middle East and continues to get things all wrong, notably today, when he actually stated in a column that "the Assad clan may have been a convenient enforcer at times for Israel and the West." A more false statement about the Assads is difficult to conjure.

Mar. 17, 2022 update: Clifford D. May points out that Russia's invasion of Ukraine has shredded Friedman's much-touted "Golden Arches Theory of Conflict Prevention," the postulation that two countries hosting McDonalds will not go to war:

He may have been correct in asserting that "when a country reaches a certain level of economic development" most of its people "don't like to fight wars." What he failed to appreciate is that if those countries are unfree, undemocratic, and ruled by tyrants, most of its people don't matter.

And to quote Liel Leibovitz from the next entry: "Grudges hundreds or thousands of years old did not dissolve with a single Big Mac order."

July 14, 2024 update: In an article by Liel Leibovitz titled "What Happened to Thomas Friedman?" comes this quote from David Samuels, a former senior writer at the New York Times Magazine, comparing two very prominent Jews from Minnesota:

While Bob Dylan created himself as an American outsider who spoke only in riddles, Thomas Friedman is a professional sycophant who speaks in clichés. Using his skills as a salesman, he marketed misguided ideas about the Middle East, technology, and China to an audience of Americans uninterested in deep thinking. And like Dylan himself, Friedman can't stop performing. He is the house poet of mediocrity, arrogance, and foolish naivety.

Leibovitz himself adds that

The man who started his career as a brilliant journalist and continued it as an influential columnist with big and ambitious ideas, is now ending it as a hollow mouthpiece of the elites he dreamed all his life of belonging to, elites whose flaws are increasingly laid bare for all to see.

Finally, this from Michael Doran:

Friedman is probably unaware that he has become a mouthpiece for the [Biden] administration. He probably believes he is still thinking independently and drawing his own conclusions. It's just a pure coincidence that 100% of his conclusions support the dogmas of the Democratic Party. ... I now read him as one reads columnists in the Russian, Chinese, and Arab press: no longer to learn new and surprising things about the world, but to see what the regime wants me to believe.