The political poster had a short but eventful life. It took form in late 1914, as the armies of Europe stagnated and governments needed new ways to mobilize troops, maintain civilian enthusiasm, increase economic production, and borrow money. In the course of World War I, poster artists developed extravagant mechanisms for portraying the purity and strength of one's own soldiers and the harrowing evil of the enemy's. Totalitarian governments drew on these same motifs during the interwar years; and all combatants used them during the Second World War. Then the political poster rapidly lost significance after 1945, a victim of television.

The political poster had a short but eventful life. It took form in late 1914, as the armies of Europe stagnated and governments needed new ways to mobilize troops, maintain civilian enthusiasm, increase economic production, and borrow money. In the course of World War I, poster artists developed extravagant mechanisms for portraying the purity and strength of one's own soldiers and the harrowing evil of the enemy's. Totalitarian governments drew on these same motifs during the interwar years; and all combatants used them during the Second World War. Then the political poster rapidly lost significance after 1945, a victim of television.

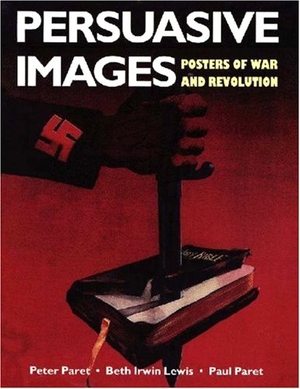

Paret, Lewis, and Paret have selected 312 posters (mostly issued in the United States, United Kingdom, France, Germany, and Russia) from the Hoover Institution's unique collection, and Princeton University Press has produced a beautiful volume featuring their illustrations. The authors' sparkling commentary points out recurring themes, the quirkiness of national styles, and the evolution from fussy detail to bold simplicity.

Of the many persuasive images - mothers, lovers, workers, capitalists, beasts, invalids, victims - perhaps the most memorable are those of the individual foot soldier. One's own stands heroic or stoic, the enemy's retreats cowardly. And while no single poster captures the many-sided reality of infantry life, together they convey something approximating its exultation, terror, boredom, and pain.

A 1930 Soviet poster from "Persuasive Images": "We will smite the kulak who agitates for reducing cultivated acreage." |