Until now, there has appeared no party in the Arab world that can compete with the SSNP for the quality of its propaganda, which addresses both reason and emotion, or for the strength of its organization, which is effective both overtly and covertly. By virtue of its organization, this party succeeded in creating a very powerful intellectual and political current in Syria and Lebanon.

- Abu Khaldun Sati' al-Husri

To the extent they pay it attention, observers of Middle East politics tend to dismiss the Syrian Social Nationalist Party, or SSNP, as a historical curiosity. Over a period of four decades, for example, The Economist has called it many names. In 1947 it was "an activist right-wing movement of a slightly dotty kind"; in 1962, it was "lunatic fringe," "farcical," and "idiotic"; and in 1985, it was "an odd little organisation."' Michael C. Hudson, a scholar of Lebanese politics, termed the SSNP's politics "bizarre" and its ideology "thwarted idealism twisted into a doctrine of total escape."

To the extent they pay it attention, observers of Middle East politics tend to dismiss the Syrian Social Nationalist Party, or SSNP, as a historical curiosity. Over a period of four decades, for example, The Economist has called it many names. In 1947 it was "an activist right-wing movement of a slightly dotty kind"; in 1962, it was "lunatic fringe," "farcical," and "idiotic"; and in 1985, it was "an odd little organisation."' Michael C. Hudson, a scholar of Lebanese politics, termed the SSNP's politics "bizarre" and its ideology "thwarted idealism twisted into a doctrine of total escape."

There is reason for this disparaging treatment. From its founding in 1932 until the present time, the party has fallen short in virtually everything it attempted. Quixotic conspiracies, foiled coup attempts, and unpopular ideological efforts won it a reputation for ludicrous impracticality, and for not being serious. It always remained numerically very small and never got even close to power. In the SSNP record, frustration far outweighs achievement.

But the SSNP's failures should not obscure the fact that the party has had profound political importance in the twentieth-century history of Lebanon and Syria, the two states where it has been most active. It provided the minorities, especially the Greek Orthodox Christians, with a vehicle for political action. As the first party fully to embrace extreme ideals of the inter-war period, the SSNP incubated virtually every radical group on those two countries; it had, in particular, great impact on the Ba'th Party. Finally – and this may mark the apogee of its power – the government of Hafez al-Asad has allied with the SSNP and incorporated some of its ideas into Syrian state policy.

For these reasons, the Syrian Social Nationalist Party deserves to be better known and studied. While the account that follows does no more than sketch out the impact of the party, I hope that this appreciation may inspire more work on the SSNP. Research should not be difficult, for the SSNP is a party of intellectuals, and the organization and its membership have produced voluminous materials.'

Party and Ideology

The Syrian Social Nationalist Party (al-Hizb al-Suri al-Qawmi al-Ijtima'i) or SSNP has at times been known as the Syrian Nationalist Party or the Social Nationalist Party, both abbreviated as SNP; French mistranslations of its name are also used in English-the Parti Populaire Syrien or the Parti Populaire Social, abbreviated as PPS.

Antun Sa'ada (1904-1949), founder of the Syrian Social Nationalist Party. |

The SSNP stands for three main tenets: radical reform of society along secular lines, a fascist-style ideology, and Greater Syria. Although best known for its Pan-Syrian ideology, a considerable portion of the party's appeal and influence had to do with its secular and fascistic elements. Indeed, it is hard to say which feature had the most importance in attracting members.

The reform program is summed up in five principles: separation of church and state, prohibition of the clergy from interfering in politics, removal of barriers between sects, abolition of feudalism, and the formation of a strong army. The first three principles are secularizing – they call for the withdrawal of religion (i.e., Islam) from public life – while the latter two fit under the modernizing rubric. It should be kept in mind that while these views are common, even banal in the West, they struck Lebanese and Syrians of the 1930s as novel. Together, the reform principles constitute a social transformation that accounts for the second "S" in the party name.

A note of caution: because Sa'ada reflected the fascist thinking of the 1930s, the words "social" and "national" are sometimes joined together to form the combination "national socialist," Hitler's coinage and the basis of the word Nazi. This is a mistake, however, for Sa'ada used the word in Arabic for "social" (ijtima'i) not "socialist" (ishtiraki); the proper noun form for his ideology in English is not National Socialism but Social Nationalism.

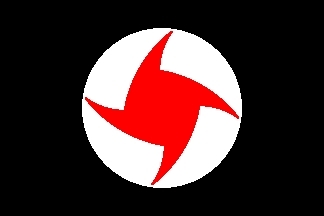

The SSNP flag. |

Fascists and Nazi sympathizers flocked to the SSNP as the only party in the Levant sympathetic to their viewpoint, and they appear to have formed a significant portion of the party's core membership. Some members were drawn by the fierce opposition to Communism. Others sought a strong leader, something Sa'ada offered in the fascist style of the 1930s. Adulation of Sa'ada was so extreme, the SSNP slogan during his lifetime was "Long live Syria! Long live Sa'ada!" There were also strong hints of his being the prophet of a new religion. SSNP recruits joined the party in a ceremony known as "baptism," at which they formally renounced other loyalties.

The third key characteristic of the SSNP is Pan-Syrian nationalism, the goal of building a Greater Syrian state. This requires some explanation. The exact definition of Greater Syria has varied at different stages of the party's history, but it always included the four modern states of Syria, Lebanon, Israel, and Jordan, as well as parts of Turkey. Late in Sa'ada's life, he extended Syria to include the Sinai Peninsula, all of Iraq, and even Cyprus. The SSNP platform makes the unity of this area a central tenet: "[Greater] Syria is for the Syrians, and the Syrians are a complete nation." In contrast to the all-important Syrian nationality, the Arab, Muslim, Christian, Lebanese, and Palestinian identities are deemed inconsequential. This point of view pits the SSNP against Pan-Arabists and pious Muslims, as well as Lebanese and Palestinian separatists.

One representation, showing maximal SSNP ambitions in red, includes Iraq, Cyprus, and Sinai. |

To create a state that represents the Syrian identity means eradicating the polities delineated by the British and French in the years after World War I – the Syrian republic, Lebanon, Israel, and Jordan. Viewing these existing states as artificial and meaningless, the SSNP pays them no loyalty. With regard to Lebanon, for example, Sa'ada declared, "Above all, we are Pan-Syrian nationalists; our cause is the cause of [Greater] Syria, not that of Lebanese separatism." He argued that "Lebanon should be reunited with natural Syria" and explicitly stated that his goal was "to seize power in Beirut to achieve this objective."

To assess the import of Sa'ada's views on Greater Syria, it has to be understood that Pan-Syrianism has two forms, the pragmatic and the pure. Pragmatists and purists differ in their view of the great ideology of the central Middle East, Pan-Arab nationalism. The first group accepts it, the second rejects it.

Pragmatists contend that Greater Syria forms part of the Arab nation and its creation is a stepping stone toward a Pan-Arab polity. For them, the unification of Syria is not an end but a means toward building a much larger unit. King 'Abdallah of Jordan was perhaps the most prominent and articulate of the pragmatists. Purists seek something quite different: a Greater Syrian state complete in itself without reference to a larger union. For them, Syria has no connection to an Arab state. A pure Pan-Syrianist cannot accept Syria's submergence in a larger Arab entity. If Syrians are a nation, then the Arabs are not; Sa'ada argued that "the Arab world is many nations, not one." He scorned efforts to bring together the many nations of the Arabs as unfeasible and counterproductive.

A Pan-Arabist can accept the pragmatist's goal but must deny the purist's. Greater Syria is fine so long as it helps build the Arab nation; as an end in itself, it is anathema. The Pan-Arabist rejects the pure Pan-Syrianist view that Greater Syria has political significance in itself; in the words of Edmond Rabbath, "There is no Syrian nation. There is an Arab nation."

Pure Pan-Syrianists disagree with Pan-Arabists on a host of other matters as well. Pan-Syrianists, for example, see the conflict with Israel as an internal Syrian affair in which the Arabs have no business. According to Sa'ada, "there is no need for Egypt or the Arabs to participate in the defense of Palestine." In contrast, Pan-Arabists see a direct role against Israel for every state between Morocco and Oman.

The Syrian Social Nationalist Party is virtually the only exponent of pure Pan-Syrianism. It does so with the knowledge that this position denies the validity of Pan-Arabism, a widely cherished political tenet. Sa'ada consciously adopted a very controversial position, one that distinguished the SSNP not only from general intellectual trends but even from the great bulk of Pan-Syrian nationalists. The disrepute of pure Pan-Syrianism goes far to explain why the SSNP is dismissed as eccentric; add the secularism and fascism, and its frequent persecution becomes understandable.

A Minority Movement

Why then did the SSNP adopt these unpopular principles? In part, because of the background of its founder and first leader, Antun Khalil Sa'ada. Born to a Lebanese Greek Orthodox family in 1904, Sa'ada spent the critical years of his youth outside Lebanon. His father, Khalil Sa'ada, lived in Egypt for several years before World War I and Antun joined his father in São Paulo, Brazil, in 1920. Although a medical doctor, the elder Sa'ada published a journal, al-Majalla, which promoted independence for Syria, secularism, and anti-confessionalism.

He also founded the National Democratic Party in Buenos Aires and chaired the first Syrian National Congress after World War 1. These influences clearly affected the theories of Antun Sa'ada, who returned to Lebanon in 1929 and founded the SSNP in November 1932. The family's years abroad, and especially those in Egypt, go far to account for the characteristic elements of Sa'ada's thought: his deep belief in a Syrian identity, his rejection of the Arab identity, and his secularism.

Syrians constituted a small but highly influential community in Egypt from the eighteenth century on. Although playing a major role in the country's commercial, industrial, and intellectual life, they never lost their separate identity or forgot their foreignness. To the contrary, the Syrians took pride in the many points of difference between them and the native population. As Egyptian nationalism grew in the late nineteenth century, the Syrians' sense of being apart became more acute. Thomas Philipp writes that "Syrians who had arrived during the last two decades of the nineteenth century had to realize that they would remain marginal and barely tolerated in Egyptian national politics. As emigrants in a foreign surrounding, they had, indeed, been made aware of their 'Syrianness'."

The psychology of Syrians in Egypt bore on Khalil Sa'ada's and then Antun Sa'ada's ideas in several ways. First, Egyptians perceived all those from the Levant area as Syrians; if residents of Jaffa and Aleppo felt nothing in common before arriving in Egypt, they gained some sense of solidarity after living there a while. Second, in contrast to Syrians living in Greater Syria, who casually equated being Syrian with being Arab, Syrians in Egypt drew a sharp distinction between the two notions. Noting that Egyptians too speak Arabic, they tended to consider themselves Syrians, not Arabs. Sa'ada's views probably originated in this perception. Third, whether Muslim, Christian or Jewish, Syrians in Egypt felt a kinship for each other (in strict contrast to those who never left Syria) and organized themselves without much regard to religion. Sa'ada's effort to ignore religion as a political force may well have derived from this outlook.

Other reasons for the party's unpopular views had to do with the SSNP's appeal to non-Sunni minorities. Secularism offered them a level playing field, erasing their historic disabilities. Christians endured the indignities inherent in the dhimmi status; Shi'is suffered from centuries of persecution at Sunni hands.

For its part, pure Pan-Syrianism held up as an ideal a geographic unit in which non-Sunnis constitute about half the population; in contrast, they almost disappear in larger Arab units. By bridging the historic gap between Muslims and Christians, Pan-Syrianism promised full citizenship and equality for the latter; by glorifying pre-Islamic antiquity –the civilization that Islam vanquished – it celebrated the common past; and it offered a state that would include nearly all Orthodox Christians within its confines. (Being thinly spread through a large region, the Orthodox, unlike the Maronites, could not retreat to their own homeland; but this was one way to bring their whole community together.)

Choosing to appeal to minorities had a major drawback, of course; it rendered widespread Sunni Arab support impossible. Most Sunnis rejected secularism and pure Pan-Syrian nationalism, the two dimensions of the SSNP program. Secularism challenges some of the basic precepts of Islam; the few Muslim thinkers who have publicly espoused the withdrawal of religion from politics have been at best ignored, at worst put on trial and executed. Similarly, pure Pan-Syrianism violates the spirit of Islam. It disregards religious distinctions, equates non-Muslims with Muslims, glorifies pagan antiquity, and puts undue emphasis on the history, culture, and bloodlines of a territory. Extreme attachment to a piece of territory is un-Islamic – not precisely against the religious law, but very much against its spirit. On the positive side, Pan-Syrianism does attract those few Sunni Arabs who reject Islamic ways and want to reach across the religious divide.

The intense opposition of most Sunnis to pure Pan-Syrian nationalism doomed the SSNP's chances to achieve its ambitions. The Greek Orthodox (alone or in combination with other minorities) could not dominate a Greater Syrian state; even if they did, the experience of the Maronites – who tried to impose a minority ideology in Lebanon and failed – suggests they would not prevail for long.

But Sunnis were not the only ones to oppose the SSNP. Its violent, irredentist, secularist, and fascist qualities assured hostile relations with almost everyone. French authorities proscribed the party during the Mandate because it agitated for independence. Gamal 'Abdel Nasser of Egypt persecuted the SSNP because it opposed the 1958-1961 union with Egypt (a non-Syrian state). Israel fought the party because of its extreme anti-Zionism. Ba'thists rejected its pure Pan-Syrian ideology. Socialists and Communists opposed its fascism. Leaders of independent Lebanon suppressed the SSNP because it denied the state's legitimacy. Syrian rulers sought to silence a proven troublemaker.

King 'Abdallah of Jordan (r. 1921-51), the other foremost exponent of Greater Syria, battled the SSNP. |

The better to harass the SSNP, its many enemies frequently charged the party of collaborating with foreign powers and doing their dirty work. French authorities accused it of collaboration with the Axis powers in the 1940s; the Vichy government, ironically, continued to press this charge. Rumors of American subsidies – which subsequently were proven accurate – discredited SSNP candidates in the Syrian elections of 1953. Nasser later accused the SSNP of taking American money. A British hand was suspected behind the 1961 coup attempt in Lebanon. Talk in recent years has (with good reason) centered on Romanian and Soviet aid.

With so many enemies, it is not surprising to find the SSNP persecuted through most of its existence. Sa'ada himself was imprisoned twice by the French, in November 1935 and August 1936, and finally executed by the Lebanese police after a hasty trial. In Lebanon, the party frequently alternated between legality and illegality. It was banned for the first time in March 1936 and made legal in May 1937; banned in October 1939 and made legal by Camille Chamoun in May 1944; banned in July 1949 and made legal by Chamoun again in September 1958; banned in January 1962 and made legal by Kamal Jumblat in 1970. (It remains legal since 1970.) In Syria, the party was legal until 1955 (and so the party headquarters were in Damascus from 1949 to 1955) but has been banned since then. In Jordan, assassinations carried out by SSNP members caused it to be repressed during 1951-1952; and the Jordanian security services tried to eradicate the party in 1966.

Despite strong official disfavor, the SSNP has on occasion won representation in the Lebanese and Syrian parliaments. In Lebanon, it took one seat in the 1957 elections. It did better in Syria, winning nine seats in 1949, one in 1953, and two in 1954. Though far too few to pass any legislation, these representatives gave the party a platform to make its views more widely known.

Hiding The Message

But the SSNP has not always wanted its true views known. To protect itself from persecution, it has frequently resorted to stratagems for obscuring the message of pure Pan-Syrian nationalism. To use the language of Islam, the party in effect engaged in taqiyya (dissimulation to preserve the faith) of an ideological nature. It adopted a variety of covers, including pragmatic Pan-Syrianism, local patriotism, Leftist rhetoric, and even Pan-Arabism.

Sa'ada made pragmatic Pan-Syrian statements on occasion, touching up his plans for Greater Syria with specks of Pan-Arabism. He would portray the realization of Greater Syria as a step toward Arab liberation. "First the Social Nationalist revival of Syria, then cooperative politics for the good of the Arab world. The rise of the Syrian nation liberates Syrian power from foreign authorities and directs it toward arousing the other Arab nations, helping them progress." Sa'ada would go further, placing Syria in an Arab framework: the fact that "the Syrian nation [umma] is part of an Arab nation [umma] does not contravene its being a complete nation with right to absolute sovereignty."

Sa'ada also developed a peculiar concept, "the Arabism of Syrian Social Nationalism," which attempted to square the circle by postulating Syrian leadership of the Arabs." He went so far as to claim, "if there is a real, genuine Arabism in the Arab world, it is the Arabism of the SSNP," and used this to justify his argument that "the Syrian nation is the nation suited to revive the Arab world."

During the 1956-1967 period, when Pan-Arabism had attained the peak of its popularity, the party muted its Pan-Syrian goals. An SSNP leaflet proclaimed two contrary slogans on one page: "Syrian nationalism against Arab nationalism," and "The SSNP supports the Fertile Crescent, a historic and geographic reality, as the only valid form of union in the Middle East – without rejecting the possibility of an Arab front." This double message makes it hard to believe that the SSNP underwent a genuine change of heart; references to the pure Pan- Syrian ideas of old lead this observer to conclude that Sa'ada's vision remained at the heart of the SSNP ideology.

But hints of local patriotism can be found as early as May 1944, when loyalty to Lebanon served as a useful cover and the party stated its goal to be "the independence of Lebanon." Ten years later, to defend the status quo from the radical Pan-Arabist programs advocated by Nasser, the Ba'th and others, SSNP leaders adopted a pro-Western outlook and made common cause with conservatives. This tactic culminated in 1958, during the civil war in Lebanon, when the SSNP joined the Lebanese government to suppress the rebels; given the party's views on the illegitimacy of Lebanon's very existence, this was a remarkable stand. This too represented not a change in long-range goals but an appreciation of Lebanon as refuge; SSNP leaders rightly feared that a victory by the government's opponents would close the country to them.

But the real need for dissimulation came in 1962. As a result of the fiasco of December 1961, when it failed in an attempt to overthrow the Lebanese government, the SSNP found itself banned in Lebanon (as well as Syria). To become acceptable again in one or another of these states, it adopted three strategies. First, as in 1944, members feigned local patriotism. Those who lived in Syria pledged loyalty to the regime in Damascus; likewise, those in Lebanon portrayed themselves as devoted to the preservation of Lebanon's independence.

This tactic was tried out at the military tribunal set up to punish the participants of the failed coup, but had little success, as neither the public prosecutor nor the presiding judge were fooled. The former told the judge:

The object of the SSNP conspirators must be obvious to you and to all the world – it was none other than the implementation of the Party's basic principles [by taking power in Lebanon]. Lebanon was aware of this fact from the very beginning. But when the conspirators failed, they tried to fabricate reasons for their conspiracy, feigning concern for reform of the regime in Lebanon and for social development.

The judge concurred: "Its goal being contrary to the law, the SSNP acted like a secret society and did not reveal its real doctrine to the authorities. Instead, ... the party pretended to be working to preserve the Lebanese entity." The implausibility of this tactic seems to have led to its abandonment.

Second, the party abandoned fascist doctrines and adopted the more acceptable rhetoric of the Left. This transformation was completed by 1970 and permitted the SSNP soon after to make common cause with those groups seeking to overturn the status quo. Close relations were developed with several parties, especially the Progressive Socialist Party of Jumblat and the PLO. The move from right to left appears long-lasting; by 1984, the SSNP chief was attending the anniversary celebration of the Lebanese Communist Party. Those unacquainted with the party's ideology even see it as a Marxist. What began as dissimulation may have, with time, become reality; the SSNP orientation today appears to be permanently aligned with the Left.

Third and most important, SSNP members took to portraying Greater Syria as the first step toward either a unified Arab front or (this was increasingly the case in later years) a single Arab nation. In other words, they adopted the protective coloring of pragmatic Pan-Syrian nationalism. One of the defendants at the 1962 tribunal of the SSNP declared that "the statement of faith in Greater Syria, in the Syrian nation [umma], ... is the same as belief in the Arab nation." Syria constitutes a nation; the Arab front consists of many nations – including, preeminently, that of Syria. (When challenged by Pan-Arabists to drop all vestiges of Greater Syria, the SSNP refused, of course; it did so on the grounds that the formation of a Greater Syrian state represents a practical intermediate stage toward the realization of a single Arab nation.)

Although the mixing of Pan-Syrian and Pan-Arab themes became more consistent after 1962, it had long been standard Party taqiyya. Already in 1951, 'Isam al-Mahayiri, an SSNP member of the Syrian parliament, argued that "our work for the unity of Natural Syria [i.e., Greater Syria] is the cornerstone for every sound Pan-Arab building." Thirty-four years later, when Mahayiri was leader of the party, he still maintained the same dissimulation, telling an interviewer that the SSNP and Damascus "agree on clear Pan-Arab objective." In 1988, the contradiction remains: despite firmly held and well-known positions, the SSNP brandishes a slogan of "Commitment to the party's policy of struggle and pan-Arabism."

Incubating Radical Politics

Much of the SSNP's importance lies in its influence over a wide range of radical elements in Lebanon and Syria.

From its inception, when Sa'ada spent time inveighing at students at the American University of Beirut, the party attracted mainly an educated elite in Lebanon and Syria. It was the first party in the region to articulate a radical, secularist position without equivocation or ethnic bias. For many of the brightest and most ambitious young minds, this quality made it stand out during the twenty or so years after its founding in 1932. Though always numerically very small (estimates range between 120 to under 1,000 members in 1936), an impressive list of former members went on to become major figures in Lebanese and Syrian life.

The poet Adonis ('Ali Ahmad Sa'id) identified with the SSNP in his youth. |

As a well-organized and highly disciplined organization with a clear doctrine and an authoritarian leader, the SSNP had strengths others sought to copy. A number of former members took what they learned from it about political organization to begin their own parties. These included:

(1) Jumblat, the Druze leader in Lebanon, founded the Progressive Socialist Party in 1949 after negotiations to cooperate with the SSNP fell through.

(2) Shishakli modeled the Arab Liberation Movement (founded in August 1952) on the SSNP.

(3) Akram al-Hawrani, a leading figure in Syrian politics for many years, was one of the SSNP's first members. During his open association with the party, in 1936-1938, he helped found the National Youth Party and then in 1939 became its leader. Not only did Hawrani himself secretly remain a member of the SSNP but he also affiliated the National Youth Party with it. Hawrani eventually broke with the SSNP and cut ties between the National Youth Party and the SSNP. As in Jumblat's case, negotiations for cooperation with the SSNP failed, so Hawrani turned the National Youth Party into the Arab Socialist Party in January 1950. This latter organization remained independent only three years, being eventually merged with the Ba'th Party in February 1953.

(4) The SSNP found a wide following among Palestinians in the early 1950s, a number of whom subsequently held high positions in al-Fath, the Palestinian organization. Sa'ada's son-in-law, Fu'ad Shimali, had a key role in Black September. Bashir 'Ubayd worked closely with the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine. Ahmad Jibril headed his own organization, the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine-General Command. Georges Ibrahim 'Abdallah quit the SSNP in 1965 to join with George Habash's Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine.

(5) In 1979 or 1980, 'Abdallah went on to found his own organization, the Lebanese Armed Revolutionary Fraction (known by its French acronym, FARL), most of whose members came from the SSNP. FARL worked with Syrian intelligence and was held responsible for a rash of terrorist acts in France during the 1980s.

Even without a direct personal connection, the SSNP often provided a model for other political parties. The Phalanges Libanaises, the leading Maronite organization founded in 1936, adopted much from the SSNP; so too did al-Najjada, the Sunni organization founded a year later. Before establishing the Ba'th Party, Michel 'Aflaq and Salah al-Din al-Bitar apparently had long conversations with Sa'ada.

The Pan-Arab theorist Abu Khaldun Sati' al-Husri, no friend of the SSNP, explained the reasons for this influence in the early 1950s: "Until now, there has appeared no party in the Arab world that can compete with the SSNP for the quality of its propaganda, which addresses both reason and emotion, or for the strength of its organization, which is effective both overtly and covertly. By virtue of its organization, this party succeeded in creating a very powerful intellectual and political current in Syria and Lebanon." Before the SSNP, political parties in Syria and most of the Middle East represented personal interests, even if they pretended to pursue causes; the SSNP was the first true indigenous party of an ideological nature. A historian of political parties in Syria is, therefore, correct to conclude that the SSNP was founded on "a completely different basis from the parties that preceded it or followed it."

The radicalism of the SSNP profoundly affected the nature of Pan-Arab nationalism. Elsewhere in the Arab world – Arabia, Egypt, and the Maghrib – Pan-Arabism first developed as a modest doctrine advocating harmonious political relations and cooperation in finances, culture and other spheres (what is known as moderate Pan-Arabism). But in Greater Syria, Pan-Arabism meant something far more ambitious and disruptive: the elimination of borders and the fusion of peoples (or radical Pan-Arabism). It appears that this latter idea can be traced back to the SSNP, whose plans to dismantle the boundaries dividing Greater Syria were subsequently transferred to the Arab nation. The Ba'th adopted SSNP-style principles in the late 1940s and then disseminated these to Egypt and throughout the Arabic-speaking countries. Radical Pan-Arabism flourished from about 1958 to 1967 and had vast political importance in the Middle East during that period. Although since overtaken by moderate Pan- Arabism, the ideology still lives on for some leaders, such as Mu'ammar al-Qadhdhafi of Libya.

In addition to its ideology and organization, the SSNP's devoted paramilitary forces gave it a capable militia which played a significant role in both Lebanese civil wars. In 1958, these stood with the government of Chamoun against the rebels. By the time fighting began in 1975, the SSNP had switched sides and played a small but important place in the anti-government coalition.

The SSNP has inspired many efforts to unify countries. In 1949 alone, it had connections to the three Syrian military rulers who pursued unity negotiations with Iraq, though each of these changed his mind or was overthrown before agreements could be reached. The SSNP's willingness to use subversion and violence won it powerful allies. On at least three occasions it received external outside backing for planned revolutions. Syria helped a 1949 attempt to overthrow the Lebanese government; 'Abd al-Illah, uncle of the king of Iraq, supported the SSNP in an unsuccessful 1956 effort to overthrow the government of Syria; and Lebanese military officers joined the December 1961 putsch against their own government. (The British government may also have had a role in this last effort.) Like almost all that the SSNP did, these incidents came to nought.

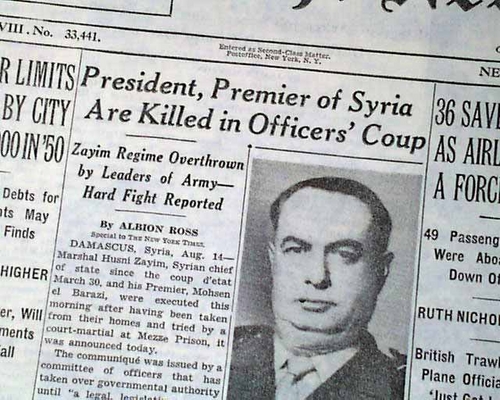

New York Times coverage of Husni Za'im's overthrow and execution in 1949. |

An SSNP attempt to overthrow the Syrian government in April 1955 failed (of course), but it had a key role in the subsequent turn of Damascus toward the Soviet Union. The party had a prominent part in the events that led up to the Lebanese civil war breaking out in 1975.

From the late 1940s on, the Ba'th party was the SSNP's closest rival in Syria. It offered a similar set of attractions to roughly the same constituency. The history of these two parties is, to say the least, tangled. Perhaps the most striking thing is that, after engaging in a rivalry that culminated in open feuding during the late 1950s, they became steadfast allies twenty years later.

The Ba'th Party was founded in the 1940s by two Syrian teachers from Damascus, Michel 'Aflaq and Salah ad-Din al-Bitar. The party promoted a radical Pan-Arabist ideology calling for the elimination of existing Arab states and their replacement by a single Arab nation. The Ba'th emerged as a major force in Syria in 1957 and members of the party have ruled Syria since 1963 (and Iraq since 1968).

In their early years, the SSNP and the Ba'th Party shared a similar base of membership and means of recruitment. They competed for adherents primarily among the educated, radically minded non-Sunni minorities. Members tended to be lower-middle-class students with ex-peasant fathers newly arrived in a town. This said, the Ba'th seems to have had a more urban and Sunni makeup.

Both recruited heavily in government district high schools (which were elite institutions at that time), especially in the predominantly 'Alawi region of Latakia and the Druze region of Jabal Druze. Occasionally, as in Latakia during the 1940s, the two parties sponsored rival high schools. Both relied on teachers to spread their ideas. The Ba'th claimed as many as three-quarters of the high school students in Aleppo and its cells were active in all parts of the country by the late 1940s. Between them, they blanketed all the high schools of Syria. According to Michael H. van Dusen, "by the early 1950s, there was not a single high school graduate who had not had some exposure to the Ba'th Party or SSNP while in school."

Both parties advocated a program calling for secularism and state control of the economy. Secularism has a self-evident appeal for peoples long persecuted on account of their religious beliefs. State control of the economy (whether the SSNP's fascist version or the Ba'th's socialist one) held out the promise of economic opportunity.

The two shared much else in common, including: elite membership (as late as 1963, the Ba'th reportedly had only 400 members); a reliance on conspiratorial methods; a vision of binding the peasants to the middle classes through industrialization; and a hope of fomenting revolution by mobilizing and enfranchising the dispossessed. And, very important for the future of Syria, both continued to influence military officers who had been party members as high school students; whereas the lower ranks mostly supported the SSNP, officers gravitated toward the Ba'th.

Members of the poorer and weaker religious communities in Lebanon and Syria found these two parties attractive and joined them in disproportionately large numbers. Indeed, it was not uncommon for members of the same family to split allegiance between the SSNP and the Ba'th. The Jadids, an 'Alawi family, were a prominent example. Two brothers, Ghassan and Fu'ad, participated in the SSNP's April 1955 assassination of the Ba'th officer 'Adnan al-Maliki, resulting in Ghassan's murder and Fu'ad's imprisonment; a third brother, Salah, had apparently been an SSNP member before joining the Ba'th Party and rising to become ruler of Syria in the late 1960s.

Initially, the SSNP had greater success than the Ba'th, for while both received 'Alawi backing, the SSNP also attracted Orthodox Christians. Both parties expanded in membership and influence in the early 1950s. The Ba'th caught up with the SSNP about this time and passed it a few years later. The disparity grew henceforth, with the Ba'th eventually become the ruling party in two states while the SSNP remained a small and widely despised movement. In retrospect, it appears that the Ba'th Party ultimately had to vanquish the SSNP. Temperamental, intellectual, organizational, and tactical factors help explain its greater success.

Temperamentally, the two parties differed in their willingness to accommodate a wider public, especially the Sunnis. Whereas Sa'ada followed his own logic to its conclusion, Aflaq and Bitar molded their ideology to prevailing currents. Ba'th leaders made some effort to attract Sunni Muslims; those of the SSNP did not. For this reason, most Sunnis could not stomach the SSNP. Joining the SSNP was always a more radical act than joining the Ba'th because the SSNP rejected tradition entirely in its quest for a new order. This contrast can be seen with regard to Pan-Arabism, Islam, and the role of religion in politics.

The SSNP's adamant rejection of Pan-Arabist nationalism very much diminished its appeal. Pan-Arabism feels congenial to Sunnis. Much of its draw lies in the compromise Pan-Arabism offers between the old aspiration to Islamic solidarity and the modern drive for nationhood. Pan-Arab nationalism upsets Muslims less than other kinds of nationalism (including the Pan-Syrian variety) because it conforms to many views commonly found among Muslims and can be grounded in Islamic sensibilities. Fueled by Nasser's charisma, Pan-Arabism gained enormous popularity in the 1950s and the Ba'th gained accordingly.

The two parties' treatment of Islam offers an even more striking contrast in attitude toward Sunni participation. The SSNP transformed Islam into something unrecognizable to a Muslim. According to Sa'ada, Islam has two manifestations, Christianity and Muhammadanism; these are not two distinct religions but two versions of the same religion. Sa'ada replaced the usual doctrines of Islam with new ones based on the principles of Social Nationalism; the resulting religion shared next to nothing with mainstream Islam. This bizarre view, expounded in Sa'ada's Islam in Its Two Messages: Christianity and Muhammadanism, attempted to bring Christians and Muslims together at the same time that it denigrated the substance of their faiths.

By comparison, the Ba'th view of Islam was almost conventional. 'Aflaq saw Muhammad the Prophet not as a religious leader but as an outstanding Arab national figure and emphasized Islam's integral role in the formation of Arab culture. This interpretation, which reduced Islam to a non-spiritual tradition, offended pious Muslims; but it did neatly integrate Islam into Pan-Arabism. Further, it compelled non-Muslim Arabs to pay homage to Islamic culture, and in this way brought the two together. The Ba'th thus showed some respect for Islam and aligned itself with Muslim sensibilities. The resulting program was far less offensive to Sunni sentiments than that of the SSNP.

Ba'th and SSNP secularist doctrines also repelled the Sunni Arab majority, for secularism runs contrary to the traditional interpretation of Islam; but again the Ba'th was more in harmony with the sentiments of Sunni Muslims. The SSNP never shed its stridently anti-religious and radical secularism; in contrast, 'Aflaq acknowledged the Islamic spirit and tried to accommodate it. All these reasons contributed to the SSNP remaining a party of minorities while the Ba'th attracted a fair number of Sunnis.

Pure Pan-Syrianism suffered from intellectual poverty. Pan-Arabism (whether radical or moderate) attracted many thinkers who developed a powerful and nuanced argument for the Arab nation; in contrast, pure Pan-Syrianism was promoted only by Antun Sa'ada and his idiosyncratic, if talented, band of followers. This lack of articulation goes far to account for the failure of Pan-Syrianism to be established as a reputable ideology and attract a large following.

One can go so far as to say that the anti-SSNP position was better articulated than the SSNP position. Note, for example, the case of Abu Khaldun Sati' al-Husri. Husri, perhaps the leading theoretician and exponent of Pan-Arabism, long took interest in the SSNP; he met with Sa'ada and even wrote a book about SSNP ideology. He disagreed with pure Pan-Syrianism, to be sure, but he took the SSNP seriously and argued with it respectfully. But the SSNP, reeling from its failed 1955 coup in Syria, provoked Husri and he responded in 1956 with a vicious refutation of the SSNP, dealing it a severe blow. Bassam Tibi explains this event's significance: "The massive attack of such an influential political writer as al-Husri on the SSNP, which had not yet gained a strong foothold, severely damaged its development. Husri's critique was used by all the Party's opponents."

The SSNP never succeeded in attracting many followers outside Lebanon and Syria; in contrast, the Ba'th won sizeable support in Iraq, Jordan, and other countries, all of which added to its strength.

On the tactical level, the Ba'th showed cunning and flexibility, joining with or dropping others (al-Hawrani, Nasser) as suited the moment. In contrast, the SSNP formed few alliances, remained isolated among enemies, and suffered constant persecution.

An SSNP member shot Lieutenant Colonel 'Adnan al-Maliki, a leading Ba'thist and one of the most powerful officers in the Syrian army, in 1955, leading to the SSNP's permanent eclipse in Syria. |

These steps had almost complete success; the SSNP was driven from Syrian political life and the balance between the two parties was permanently altered.

A Tool of Damascus

Though long-standing ideological rivals, the SSNP and Ba'th became bitter enemies only after the Maliki affair. It seemed certain that the hostility between the SSNP and the Ba'th would go on indefinitely, or at least until the former was crushed. During the Lebanese civil war of 1958, for instance, the Ba'th went after the SSNP with special venom. But their enmity did not continue; instead, the two parties underwent ideological and political transformations. In the process, the SSNP ended up an instrument of the Ba'th, while the Ba'th took on some of the ideology of the SSNP. This crossover led to the two becoming close, if wary, allies.

Spectacular failures suffered by both the Ba'th and SSNP in late 1961 sparked these changes. We have already seen how the SSNP's failed effort to overthrow the government of Lebanon in December led to its (public) repudiation of pure Pan-Syrianism and its refuge under the cover of Pan-Arabism. A generation later, that repudiation still stands.

The Ba'th experienced a more thorough transformation, changing inwardly as well as outwardly. In its case, the breakup of the United Arab Republic (UAR) in September 1961 precipitated changes. Formed in 1958 as a total merger of the Syrian and Egyptian states, the UAR then quickly soured. But three and a half years elapsed before Syrian officers extricated their country from Cairo's grasp. Collapse of the UAR discredited the Syrian Ba'th Party's old dream of radical Pan-Arabism. (Branches of the Ba'th Party in other states, notably Iraq, were not affected in the same way.) The travails of union with Egypt disabused all those who assumed that the formation of a Pan-Arab union would be easy; further, eliminating borders between Arab states no longer looked so attractive. The UAR debacle also strengthened the sense of being a Syrian and the attachment to this identity. After the UAR experiment, many Syrian citizens who previously had scorned their polity as meaningless came to appreciate it.

Indeed, a new strand of thinking emerged in the Ba'th Party – Regionalism. Regionalists made Syria (and not the Arab nation) their primary field of attention. So intensely did they concentrate on Syria that Sati' al-Husri, keeper of the Pan-Arabist flame, wrote disapprovingly about "the strange matter of Ba'thists taking up Syrianism." Michel 'Aflaq, the Ba'th ideologue, went so car as to accuse the Regionalists of pursuing a parochial nationalism (iqlimiyya) resembling that of the SSNP. As radical Pan-Arabism disappeared from the Ba'th program in Syria, giving way to pragmatic Pan-Syrianism, the party took on a whole new cast. For this reason, scholars have dubbed the post-1961 party the Neo-Ba'th. Further changes in government only confirmed the evolution away from Pan-Arabism. Bitar observed, with reason, that the 1966 coup "marked the end of Ba'thist politics in Syria." Michel 'Aflaq put the same sentiment more pungently: "I no longer recognize my party!"

Oddly, the events of late 1961 turned the SSNP and the Ba'th into mirror images of each other. The SSNP kept its real doctrines but adopted Pan-Arabism for cover; the Ba'th Party of Syria adopted a position congenial to the SSNP but purported to maintain its original ideology. The SSNP talked like the Ba'th, the Ba'th acted like the SSNP. There was, however, a consistency in this behavior; both parties found it advantageous to pursue Pan-Syrian goals under the cover of Pan-Arabist rhetoric. The failures of 1961 had the curious effect of compelling each party to adopt elements of the other's ideology. A former British ambassador to Syria and Lebanon, David Roberts, observes that "the Ba'th has parted company with the PPS and indeed banned it; but it has quietly absorbed its message." The crossover culminated when significant numbers of SSNP members joined the Ba'th With this, the Neo-Ba'th became almost indistinguishable from the SSNP.

The Syrian government's acceptance of Pan-Syrianism then changed relations between the SSNP and the Neo-Ba'th almost beyond recognition. Its shift toward Pan-Syrianism began in 1961 and culminated in 1974, four years after Hafez al-Asad came to power. Through a pragmatic and not a pure Pan-Syrianist (and so, potentially still a Pan-Arabist), Asad agreed on many essential matters of foreign policy with the SSNP. He sought to bring all four countries that constitute Greater Syria under the rule of Damascus; indeed, as earlier ambitions toward Egypt and other distant regions withered, this became a central objective of Syrian foreign policy. According to Laurent and Annie Chabry, the Asad government "uses the foil of Pan-Arabism to pursue a Pan-Syrian policy of the sort once promoted by the SSNP."

Mutual interests made the SSNP a client of the Syrian state and after decades of competition, the two sides became closely allied in Lebanon in 1976. In addition to a growing ideological compatibility, this may have had something to do with personal connections, for the Makhlufs, the family of Asad's wife Anisa, had a history of involvement with the SSNP. One of Anisa's relatives, 'Imad Muhammad Khayr Bey, was a senior SSNP official until his assassination in 1980. Rumor in Syria held that Anisa was sympathetic to the party and influenced Asad not just to cooperate with the SSNP, but also to look favorably on Greater Syria.

Not all elements in the SSNP accepted Syrian patronage, and this led to a series of schisms that left the party split into several factions: Maoist, Rightist (led by George 'Abd al-Masih), and pro-Syrian. In'am Ra'd led the last faction for some years; under pressure from Damascus, he was succeeded in July 1984 by 'Isam al-Mahayiri, the party's first Syrian-born and Muslim leader. Ra'd was docile enough to let himself be trotted out for foreign visitors (such as the Reverend Jesse Jackson when he visited Syria in January 1984); but Mahayiri, a lawyer and the scion of a prominent Damascene family, proved an even more willing agent. Mahayiri much understated the case when he observed that "our relations with the Syrian regime [and] the Ba'th Party ... are good and are developing." In fact, Mahayiri went to Damascus for consultations and probably for direction. Indeed, Israeli officials reportedly believed that Mahayiri took orders directly from Asad, and the Israeli defense minister, Yitzhaq Rabin, publicly characterized the SSNP as "entirely under the control of Syrian intelligence."

With Syrian money and arms, the SSNP militia became a small but significant actor in the Lebanese civil war. According to Israeli intelligence, Syrian forces allowed the SSNP unusually free movement in Lebanon – a sign of the two sides' close ties. According to Hezbollah, the two even staged joint military activities. One estimate put SSNP strength in 1975 at 3,000 troops, a sizeable number in Lebanon; and a clear hierarchy and strict discipline increased its effectiveness. One on-the-spot observer, Harald Vocke, went so far as to call the SSNP militia "the strongest fighting unit" of the anti-government forces and, following al- Fath, the Christians' "most important opponent." This is probably an exaggeration, but the SSNP militia did gain in importance following the PLO's 1982 evacuation from Lebanon. It opened offices in Syrian-controlled territory in the Bekaa Valley and ruled a portion of Lebanese territory to the south of Tripoli.

Asad also let the SSNP use Syrian media to promote its Greater Syria message. The engagement of Shawqi Khayrallah as a Syrian publicist was a striking example of this. Khayrallah had been an editor of the SSNP magazine in 1945 and he conceived of the 1961 coup in Lebanon; then he disappeared from view. In 1976, he began writing editorials for the state-run Syrian radio and newspapers promoting the concept of Greater Syria, and did not mince words. On one occasion he called for the integration of Lebanon "into a Levantine [Mashraqi] Union, currently woven by Syria, Jordan, and [Palestine]." Khayrallah also argued that the return of the Palestinians to their homeland must be based on an understanding that "Palestine is Southern Syria."

In return for this backing, the SSNP performed a number of services. It helped the Syrian effort by providing a friendly base for Syrian troops in its home area east of Beirut. Asad relied on his SSNP allies to undertake especially difficult operations in Lebanon. For example, he deployed SSNP troops against the Iranian-backed Hezbollah in June 1986. To ensure a favorable outcome, Syrian troops took up nearby positions and intervened when the SSNP needed help. Syrian troops in Lebanon looked out for the interests of the SSNP; thus, five members of Hezbollah were arrested that same month on the charge of assassinating an SSNP official.

The party was also the first (and as of this writing, the only) Lebanese group to look beyond the Israeli presence in Lebanon and call for strikes within Israel proper. Calling Zionism a "racist movement which seeks to destroy us completely as a nation," the SSNP declared itself "in a sate of continuous war against Israel regardless of any possible Israeli withdrawals from Lebanon or the land of Palestine."

Most importantly, the SSNP engaged in key acts of terrorism. Under the aegis of Asad Khardan, the party's "Commissioner for Security," suicide attacks proliferated. Ehud Ya'ari (who calls the SSNP "the oldest terrorist organization in existence") sees the party as "Syria's most reliable instrument of terror, and it is employed for particularly sensitive and dangerous operations that are beyond the capabilities of the Palestinian terror groups headquartered in Damascus." Thus, May Ilyas Mansur, an SSNP member, set off a bomb on a TWA airliner in early April 1986 that killed four passengers. The SSNP has also been tied to the attempt, just days laer, by Nizar al-Hindawi to place a bomb on an El Al plane.

Habib al-Shartuni, the man arrested for killing President-Elect Bashir Gemayel in September 1982 was a member of the SSNP. The group that claimed to have bombed the U.S. Marine barracks in October 1983 proclaimed its support for Greater Syria, making it likely that the SSNP had some role in this blast. It claimed responsibility for eight of the eighteen suicide bombings directed against Israel in southern Lebanon between March and November 1985. Pointing to the SSNP as "responsible for staging spectacular attacks and suicide actions," Israeli forces retaliated in August 1985 by destroying the SSNP headquarters in Shtaura.

These attacks not only contributed to the Israeli decision to quit Lebanon, but they had an important role in Lebanese politics: by showing that the Syrian government could match the ferocity of Shi'i fundamentalist attacks on Israel, they added to Damascus's stature. The importance that Asad attached to suicide attacks was clear from the attention he paid them. He personally endorsed suicide efforts in a May 1985 speech.

I have believed in the greatness of martyrdom and the importance of self-sacrifice since my youth. My feeling and conviction was that the heavy burden on our people and nation ... could be removed and uprooted only through self-sacrifice and martyrdom. ... Such attacks can inflict heavy losses on the enemy. They guarantee results, in terms of scoring a direct hit, spreading terror among enemy ranks, raising people's morale, and enhancing citizens' awareness of the importance of the spirit of martyrdom. Thus, waves of popular martyrdom will follow successively and the enemy will not be able to endure them. ... I hope that my life will end only with martyrdom. ... My conviction in martyrdom is neither incidental nor temporary. The years have entrenched this conviction.

With such sponsorship at the top, a cult of the SSNP suicides was perhaps inevitable: Schools, streets, squares, and public institutions throughout Syria are named after the suicide bombers, and the country's most popular singer, Marcel Khalifa, has recently monopolized the top spot in the hit parade with his anthem to the suicides. Video cassettes of the bombers' "wills" are available at sidewalk kiosks, and sales are consistently brisk.

Increasingly – and consistent with SSNP ideology – some SSNP suicides came from Syria. When asked why he joined a Lebanese movement, one bomber answered, "Is there a difference between Lebanon and Syria?" Conversely, a sixteen-year-old Lebanese girl who attacked an Israeli convoy in April 1985 with a booby-trapped car, killing herself and two Israeli soldiers, previously had made a videotape in which she sent greetings to "all the strugglers in my nation, headed by the leader of the liberation and steadfastness march, Lt. General Hafiz al-Asad." She too saw Lebanon as part of Syria.

The SSNP also provided services for Syria's allies. A member of the party shot the top Libyan diplomat in Lebanon, 'Abd al-Qadir Ghuka, in June 1983. He later told police that the Syrian secret service hired him for the attack at the behest of al-Qadhdhafi, who thought Ghuka intended to defect. Libyan money increased substantially in 1986; Qadhdhafi apparently hoped to use the party as Asad did, to shield him from direct responsibility for terrorist activities. This alliance became public in October 1987, when the SSNP announced that 250 members had signed up to fight for at least six months in Qadhdhafi's war against Chad.

For the most part, SSNP members were delighted by the Syrian regime's turn to Pan-Syrianism; after decades of tension with Damascus, it finally found an ally there in a leader committed to Pan-Syrian ideology. The SSNP leadership praised "Syria's brotherly role and heavy sacrifice" and concluded that Asad genuinely aspired to a Greater Syrian union. One of its members told an interviewer: "We cannot forget that Mr. Hafiz al-Asad – His Excellency the President of Syria – has declared many times that Lebanon is a part of Syria, that Palestine is a part of Syria. And if we believe that, and we have to – he has given all signs of being serious – it means that his interest in Lebanon is very genuine. He is playing the game very cautiously and intelligently."

Conclusion

Its legacy of frustration does not invalidate the significance of the Syrian Social Nationalist Party, which introduced a panoply of new ideas to the Middle East. These include the ideological party, complete political secularism, fascistic notions of leadership, and a dedication to pull down borders between states. The party drew in and influenced a generation of leaders in Lebanon and Syria. Its repeated challenges to the Lebanese state denigrated the prestige and status of the authorities. And its militia had a substantial role in the Lebanese civil war. Looking over a half century of turmoil, David Roberts notes that "the PPS has had a curiously pervasive influence through intrigue, murder and an ideology which rightly foresaw would be effective in the Levant."

In one sense, the SSNP in the 1980s became stronger than ever before. No longer did it have to hide and plot clandestine coups. Instead, it enjoyed the patronage of one of the most powerful Middle East states and found freedom to maneuver in Lebanon's anarchy. Syrian help has transformed the party from a moribund relic to a dynamic force. Ehud Ya'ari writes that "men who had been forgotten since the 1940s or 1950s have recently reappeared in the role of mentors, political mummies come back to life. Slogans that had long faded or peeled off walls have been restored with fresh paint, and the aura of action that surrounds the SSNP is once again attracting young people to the symbol of the red hurricane." The party also tapped new sources of members, including Shi'is and Druzes.

But the long-term implications of alliance with Syria appeared ominous for the SSNP; Asad's support had a steep price. He sought to bring the party under Damascus's control and make it a shell for Syrian agents and an instrument of Syrian policy. The potential danger is clear; by agreeing to work so closely with Syria's rulers, the party forfeited the strength that had made it an important force over the decades-its visionary politics and fierce independence. Asad's success in dictating terms restricted the SSNP's capacity for autonomous action. If money and arms from Damascus allowed the SSNP to flourish temporarily, absorption by a police state rendered its future bleak. Alliance with Damascus contained the likely seeds of the SSNP's demise.

Perhaps aware of this, the anti-Syrian wing of the SSNP attempted to depose 'Isam al-Mahayiri as party leader in January 1987. In a coup marked by SSNP factions shooting at each other at the party headquarters, Jubran Juraysh replaced Mahayiri and threatened to try him before the SSNP Higher Council.

The revolt seems to have been specifically provoked by a Syrian effort to use the SSNP to fight its many enemies in Lebanon – Hezbollah, the Druze, the Palestinians, and the Sunnis. But Mahayiri called on his Syrian patrons and reestablished his position in September 1987. Despite this limited reassertion of the party's independence, its influence appears to lie mostly in the past.

International Journal of Middle East Studies

Vol. 21, No. 4 (November 1989), pp. 607-610

http://www.jstor.org/stable/164124

NOTES AND COMMENTS

This letter is in response to the article by Daniel Pipes, "Radical Politics and the Syrian Social Nationalist Party" (IJMES, August 1988). Pipes' article seems to be based more on rumors and hearsay than on scholarly research and investigation. It fits more into one of the numerous journals on terrorism that emphasizes the sensational and the rhetorical over sober scholarship.

Pipes asserts – in what he calls a "note of caution" (p. 304) – that Sa'ada used the word ijtima'i to mean social, not socialist. If Pipes had read the Arabic sources that he claims to have read, he would know that the word ijtima'iyya was once used by some as a translation for the word socialism.

His analysis of the appeal of the party, which has always been limited, is flawed. He maintains that "fascists and Nazi sympathizers flocked to the SSNP" (p. 304). This sympathy, however, does not help explain the appeal of the party, which had more to do with the inherent problems in Arab society and the dangers that the region of the Levant faced. The party provided easy answers to complex problems confronting frustrated individuals, particularly members of the intellectual elite.

Pipes' citations are frequently inaccurate; he seems to choose sentences in order to interject footnotes rather than basing his statements on an exhaustive reading of the Arabic sources. To support his claim that Sa'ada was opposed to "the artificial and meaningless" (p. 305) Lebanese state, he cites a statement by Sa'ada in which he referred to "Lebanese separatism," a term that Sa'ada used to refer to the right-wing Phalanges' version of Lebanese nationalism and not to the entity of Lebanon per se. He also mischaracterizes the party's position on the Palestinian problem by maintaining that the conflict with Israel, according to the party, is "an internal Syrian affair in which the Arabs have no business" (p. 306). Only a person with little understanding of the party's ideology would make such an assertion.

Pipes is furthermore mistaken when he claims that the party "abandoned fascist doctrines and adopted the more acceptable rhetoric of the Left" (p. 310). While it is true that the party underwent a partial political transformation in the 1960s, it is also true that the party never abandoned its fascist doctrines, from racial categorizations, worship of al-za'im, to fascist internal organization. To support his claim that the SSNP became a leftist party, he merely states that the SSNP chief "was attending the anniversary celebration of the Lebanese Communist Party" (p. 310), a celebration attended by tens of political parties.

On page 311, Pipes lists names of personalities who were, in his opinion, members of the SSNP. He includes Elie Salem, the former foreign minister of Lebanon, although there is no evidence to indicate that Salem was ever a member of the party, or of any party for that matter. If Pipes has the evidence, he should have provided it. More surprisingly, Pipes includes Salah Jadid, the former ruler of Syria, of whom he says that he "was possibly a member." There is no evidence whatsoever that Salah Jadid was ever a member of the SSNP. Perhaps Pipes has confused Salah Jadid with his brother.

Pipes mischaracterizes the membership of the Lebanese Armed Revolutionary Brigades – not "Fraction." Most members of the Brigades came from ultra-leftist communist organizations, not from the SSNP, as Pipes claims on page 311. In order to exaggerate the influence of the party, Pipes also claims that the party of the Phalanges "adopted much from the SSNP" (p. 311). In reality, as both parties were founded during the same era, they were both influenced by the Nazi movement and not by one another.

On page 312, Pipes claims that "Michel 'Aflaq and Salah al-Din al-Bitar apparently had long conversations with Sa'ada," before establishing the Ba'th Party. For this information Pipes relies on a book by the Lebanese writer Mustafa Juha, who cannot be considered a reliable source on the matter or on any matter. His books have long been banned by Lebanese Security Forces for the malicious lies they contain, such as the Prophet Muhammad being a sexual pervert. He is also closely allied with ultra-rightist factions in Lebanon and writes propaganda publications against the leftist coalition. Juha has never known any of the persons in question and his account should be dismissed out of hand.

It is inaccurate to maintain, as Pipes does (p. 312), that the SSNP played "a significant role in both Lebanese civil wars." In fact, the party's role in both wars is marginal compared to the participation of other major parties. It is also questionable that the "party had a prominent part in the events that led up to the Lebanese civil war in 1975" (p. 313).

Pipes is also unpersuasive when he argues that Hafez al-Asad has adopted the ideology of the party. Instead of understanding Asad's policies in terms of Realpolitik, he insists on attributing his policies to the ideology of the party. He does so by using information without any evidence or citation. For example, he says: "Rumor in Syria held that Anisa [Asad's wife] was sympathetic to the party and influenced Asad not just to cooperate with the SSNP, but also to look favorably on Greater Syria" (p. 318). No evidence for such an absurd assertion is provided. No mention is made of the persecution suffered by party members who had fought with the invading Syrian army troops, at the hands of the Syrian army following its entry into Lebanon in 1976.

Pipes' claim that the SSNP had a hand in the bombing of the U.S. Marine barracks is totally unfounded; and it is untrue that Islamic Jihad ever referred to "Greater Syria." The author either does not know Arabic well enough, or he relies too unquestioningly on the mysterious sources that provided him with some of the bizarre assertions he makes in the article. Specifically, there is no evidence, and Pipes provides none, that the SSNP was involved in placing a bomb aboard a TWA airliner in April 1986. Pipes also provides no evidence for his claim that the SSNP was involved in the attempt by Nizar al-Hindawi to place a bomb on an El AI plane.

In the last section of the article Mr. Pipes cites pro-Syrian statements by certain Lebanese to underline the appeal of the SSNP. He should know that these statements are made daily by Lebanese living in areas under Syrian control, for obvious reasons. To Pipes, a pro-Syrian statement is an irrefutable evidence of an SSNP link. He also gives no evidence for his assertion that the SSNP was involved in the assassination attempt against 'Abd al-Qadir Ghuqa, who was a close ally of the SSNP.

Finally, it is odd that Pipes insists on referring to Sati' al-Husri as "Abu Khaldun Sati' al-Husri." This reference is, to any person who knows Arabic, redundant.

A firm line should be drawn between the plethora of literature on "terrorism" and real scholarship on the Middle East. It is unfortunate that this line is blurred in Pipes' article.

As'ad Abukhalil

Arlington, Va.

REPLY:

As'ad Abu Khalil's critique challenges the accuracy of my article on a host of points. Most of his disagreement (such as the reasons for the Syrian Social Nationalist Party's appeal and the changes the party underwent in the 1960s) are matters of interpretation. Restricting myself only to questions of fact, let me acknowledge that he is correct in one instance. Elie Salem was never a member of the SSNP. I apologize for this error.

But Abu Khalil is wrong on all the other specific factual items. Of course, ijtima'i was once used to mean "socialist," but not in Lebanon in the 1930s and not by Antun Sa'ada.

Abu Khalil takes issue with my assertion that the SSNP saw the conflict with Israel as "an internal Syrian affair in which the Arabs have no business." How then would he explain Sa'ada having written (quoted in my article, p. 306) that "there is no need for Egypt or the Arabs to participate in the defense of Palestine"?

Was Salah Jadid a member of the SSNP, as I write (p. 311) "possibly" was the case? I cannot say for sure, but my information derives from John W. Amos II, Palestinian Resistance: Organization of a National Movement (New York: Pergamon Press, 1980), p. 382, n. 56. Amos notes that Salah Jadid as a youth "was apparently a member of the PPS and later joined the Ba'th." In an attempt to verify the accuracy of this statement, I wrote a letter to Amos on April 27, 1988. Unfortunately, I did not receive a reply from him.

As for the Lebanese Armed Revolutionary Fraction (the usual name in English, and not Lebanese Armed Revolutionary Brigades), I said nothing about "most members," only that Georges Ibrahim 'Abdallah, its founder, had once been a member of the SSNP. This is indisputably the case, as Abu Khalil indirectly acknowledges.

Knowing something of Mustafa Juha's erratic reputation, I introduced information from his book with the word "apparently," then provided a citation to him. But his book Lubnan fi zilal al-ba'th contains much of interest. Surely, the fact that other of his writings were banned by a Middle Eastern government for containing "malicious lies" is no reason to ignore him. If this criterion were adopted, we would then also have to disregard books by 'Ali 'Abd al-Raziq, Taha Husayn, Fazlur Rahman, Sadiq al-'Azm, Mahmud Muhammad Taha, and a host of other distinguished thinkers. It would seem that getting proscribed by authorities in the Middle East is a sign of courage and creativity.

With regard to the bombing of the U.S. Marine barracks, Abu Khalil questions my grasp of Arabic and deems me too reliant on "mysterious sources"; but if he would look a bit closer at note 61, he would see that my reference for adducing a SSNP role in the incident is from Agence France Presse – neither Arabic nor mysterious!

Abu Khalil may wish to deny a SSNP role in the bombing of a TWA airliner in April 1986, but the woman who left a bomb behind on the plane, May Ilyas Mansur, has herself acknowledged being a member of the party.

Abu Khalil deems it odd that I use the name Abu Khaldun Sati' al-Husri, and uses this as basis to challenge my knowledge of Arabic. This is perhaps the most bizarre of his many protests, for Husri himself commonly used the name I have cited, and I exactly followed his usage. For examples, see the title pages of his books, Difa' 'an al-'uruba, Yawm Maysalun, and al-Iqlimiyya.

Finally, I must address the deplorable ad hominem theme that runs throughout Abu Khalil's letter. It would be a great step forward in the field of Middle East studies if specialists could disagree without indulging in innuendoes and nastiness. Like most scholars, I am pleased to learn from constructive criticism; but I am considerably less pleased to be confronted with the fulminations such as those indulged in by Abu Khalil.

And why the snide comments about my knowledge of Arabic, especially when Abu Khalil has found no errors in my reading of texts? Could this be a case of the native speaker pulling rank in the single area where he has an advantage? Worse, is it a nativist attempt to suggest that only born Arabic speakers can study their own history?

Rather than waste his time and mine with this parade of trivialities, Abu Khalil would be advised to add to our knowledge of the Syrian Social Nationalist Party by himself writing about the organization.

Daniel Pipes

Foreign Policy Research Institute

Philadelphia

Jan. 1, 1994 update: Rana Aboud, an unidentified author, replies to this article with an SSNP apologetic at "Seek Scholarly Truth not Propaganda." Oddly, this appears in volume 2, number of a journal called the Middle East Quarterly; odd because I am the editor of a new journal by that same name whose first issue will appear in a few weeks. On naming it, I had no idea that an existing journal of that same name existed.

Apr. 1, 2007 update: Eyal Zisser has written an important analysis, "The Syrian Phoenix: The Revival of the Syrian Social National Party in Syria," Die Welt des Islams, 47 (2007): 188-206. He concurs with my argument that the SSNP has lost politically but won ideologically, noting a

surprising convergence between the ruling Ba'th regime in Syria and the SSNP, its historical bitter rival. This convergence was the result of the SSNP's recognition and acceptance of defeat in its political struggle with the Ba'th, but at the same time, the Ba'th regime's readiness to adopt many of the SSNP's ideological precepts, mainly those of "Historic or Greater Syria" and of "Syrian Unity", or even a "Syrian Nation", as part of its efforts to reinforce its standing in Syria and its need to redefine its own ideological beliefs. Thus, alongside this political defeat, the SSNP held the upper hand ideologically, certainly in terms of the vision of the Syrian nation, although with an Arab cloak - a nation with a distinctive identity of its own that had sprung from the Syrian region.

Feb. 17, 2009 update: The Syrian Social Nationalist Party in recent decades has degenerated into a client of the Syrian state, where is seems likely obscurely to remain so for a good while. Its thuggery has just affected one well-known Western, Christopher Hitchens (with whom my public feud is now in abeyance). According to As'ad AbuKhalil, now an academic at California State University, Stanislaus:

At the invitation of Hariri-Saudi group, Hitchens is visiting Lebanon. A source sent me this: "I dont know if you find this as news worthy or not, but Christopher Hitchens is currently in Beirut sponsored by the same group that owns that crap NOW Lebanon. He got in a few nights ago and surprisingly went out drinking. On his way out of the bar he saw an SSNP poster and wrote on it "Fuck the SSNP". There just happened to be some SSNP thugs near by--most likely asking people for their ID, and most likely to no avail--and saw him write on the poster and kicked his ass. He is still walking with a limp."

Feb. 18, 2009 update: The Guardian provides more detail on this incident than one needs at "Christopher Hitchens on Beirut attack: 'they kept coming. Six or seven at first'."

May 1, 2009 update: Hitchens himself describes the incident at "The Swastika and the Cedar."

June 13, 2011 update: Ali Qanso of the SSNP has become a Lebanese minister of state.

Jan. 27, 2017 update: One can't predict where the SSNP will turn up; today we learn that it sponsored and accompanied Rep. Tulsi Gabbard (Democrat of Hawaii) on a sycophantic visit to Syria's dictator, Bashar al-Asad.

Aug. 5, 2017 update: A private intelligence agency, SouthFront, published photographs released by SSNP showing the SSNP fighting on behalf of the Asad regime in the Suweida region of southwestern Syria. As SouthFront explains,

The SSNP military wing is one of the major pro-government factions participating in the ongoing conflict. The SSNP's members have participated in various battles across Syria, including the provinces of Latakia, Hama, Aleppo, Homs and others.

Note the SSNP flags. |

Aug. 20, 2017 update: Moussa Oukabir, one of the jihadis who carried out an attack on pedestrians on Aug. 18 in Cambrils, Spain, posted an apparent selfie with the SSNP logo and the tag-line "Yo Soy Siria" (I am Syria).

Oct. 21, 2017 update: The Lebanese Justice Council sentenced President Bashir Gemayel's SSNP assassins to death in absentia 35 years after the murder on Sep. 14, 1982. Habib Shartouni (thought to be alive) and Nabil Alam (thought to have died) were sentenced to death. The blowing up of Phalange party headquarters killed many others as well. Arab News reports that the Justice Council session

was held under tight security at the Beirut Palace of Justice. The session was attended by two groups, one supporting the SSNP and the other the Phalange and Lebanese Forces. ... Before the session began, SSNP supporters marched toward the Palace of Justice. Security forces set up an iron barrier to separate them from Phalange and Lebanese Forces supporters.

Some protesters said Bachir's assassination was not personal, but was because he dealt with Israel and helped it occupy Lebanon and commit massacres. "What's happening today is a political trial," one of them said. Protesters chanted slogans in support of Shartouni, Syria and SSNP founder Antoun Saadeh. ...

Shartouni's lawyer Richard Riachi said: "What Shartouni did was an act of resistance protected by international law and the UN charter. What he did was a reaction to the Israeli occupation of Lebanon." The court "didn't listen to the aggrieved party," Rayachi added. "This is a political crime with a decent motivation. Shartouni didn't receive any money from any party."

Oct. 27, 2017 update: The SSNP has posted pictures of its operatives in Palmyra's ancient theater.

Aug. 22, 2019 update: Amr Salahi quotes Kellie Strom, an activist with Syria Solidarity UK in "Tulsi loves Asad: How Syria became a US presidential campaign issue":

Tulsi Gabbard's positions look like the result of a nakedly political influence campaign, where her visit to Syria was backed by members of the Syrian Social Nationalist Party (SSNP), a Nazi-like pro-Asad Syrian party. A similar influence campaign has been aimed at the UK, and the SSNP leader Ali Haidar has been central to organising trips to Damascus for various figures in the UK, notably Baroness Cox and Giles Fraser.

Sep. 21, 2021 update: I review The Rise and Fall of Greater Syria:

A Political History of the Syrian Social Nationalist Party by Carl C. Yonker in the Fall 2021 issue of the Middle East Quarterly.

Jan. 1, 2022 update: Péter Ákos Ferwagner offers a fine discussion of "Antoun Saadeh and the Concept of the Syrian Nation" in a book about Histories of Nationalism beyond Europe: Myths, Elitism and Transnational Connections.

Jan. 24, 2024 update: Lebanon's Phalange Party has called for the dissolution of the SSNP. A war of words between the two parties then ensued.

Nov. 9, 2025 update: Hussein Aboubakr Mansour has a major analysis that emphasizes the anti-Zionist and antisemitic focus of the SSNP at "The Man Who Made Zionism Into Settler Colonialism: Antoun Sa'adeh, Fayez Sayegh, and the Intellectual Genealogy of Anti-Zionism." (For a non-fire-walled version, click here.)

Nov. 9, 2025 update: Aymenn Jawad al-Tamimi, the Middle East Forum's resident specialist in Syria, comments on the current status of the SSNP in a note to me:

The concluding remarks in your study on the SSNP were an assessment of the SSNP's situation over 35 years ago: "If money and arms from Damascus allowed the SSNP to flourish temporarily, absorption by a police state rendered its future bleak. Alliance with Damascus contained the likely seeds of the SSNP's demise."

That very same analysis can be applied to what happened to the SSNP during the course of the Syrian civil war. Having already been legalized in Syria in 2005 and having joined the Ba'th-led "National Progressive Front," the SSNP – at the time led by Lebanese politician Asaad Hardan – gained some prominence during the early years of the Syrian civil war. It mobilized its members and supporters in Syria in its "Eagles of the Whirlwind" militia and fought supported the Assad regime in battles across multiple fronts in Syria in, including Homs, Raqqa, Damascus, and Latakia. The visible presence of the group on social media – together with the seats it gained in the 2016 Syrian parliamentary election – even led to speculation that the party might emerge as a future contender with the Baath Party for power and influence.

In reality, the same analysis quoted above in your 1988 study remained valid throughout the course of the civil war. In fact, the SSNP just functioned as one of multiple non-Ba'th "satellite" parties within the National Progressive Front, mobilizing support for the Assad regime's survival and not seeking fundamentally to alter, much less to undermine it. As part of its dissolution and banning of the entire National Progressive Front, the new government banned the group in Syria. Thus, standing by the Assad regime till the end ultimately led to the SSNP's demise in Syria.

Finally, Hardan's group also finds itself lacking an armed force in Lebanon, as the SSNP faction in Lebanon headed by Rabi' Banat controls the Eagles of the Whirlwind militia.

Nov. 26, 2025 update: Aymenn Jawad al-Tamimi has published an article along these lines, "The Syrian Social Nationalist Parties," in which he shows how "multiple separate entities ... have claimed the title of the SSNP in Syria and Lebanon, both during the time of the Syrian civil war and following the fall of the Assad regime in December 2024." He proceeds to list three such parties.

November 26, 2025Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi