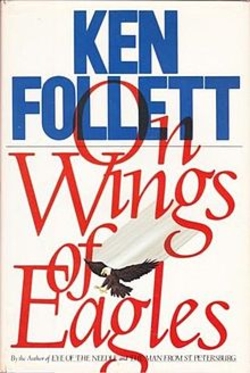

Ken Follett, author of several fictional thrillers, has now applied the formula that has worked so well in the past to a true tale. On Wings of Eagles recounts the unlikely story of an American computer company's efforts to get two of its employees out of the maelstrom of the Iranian revolution.

Ken Follett, author of several fictional thrillers, has now applied the formula that has worked so well in the past to a true tale. On Wings of Eagles recounts the unlikely story of an American computer company's efforts to get two of its employees out of the maelstrom of the Iranian revolution.

The incident attracted considerable attention from the press when it occurred in early 1979. Bill Gaylord and Paul Chiapparone, two U.S. citizens working in Iran for Electronic Data Systems (EDS), a Dallas-based computer services corporation, were jailed on December 28, 1978. They were victims of an anticorruption drive mounted during the Shah's last days in Iran, a drive far more caught up in the politics of the moment than in abstract questions of legality and truth. Consequently, the prosecutor who had them arrested did not file charges against the two; he did, however, post bail at $12,750,000.

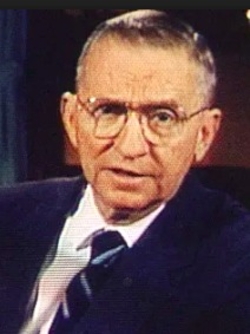

Stunned by these arbitrary arrests, H. Ross Perot, founder and chairman of EDS, mobilized both his and the company's resources to get the two employees out of jail. He became personally engrossed in the effort to release Gaylord and Chiapparone. Perot began by trying normal avenues, such as lobbying the U.S. government for help and seeking the counsel of lawyers.

H. Ross Perot. |

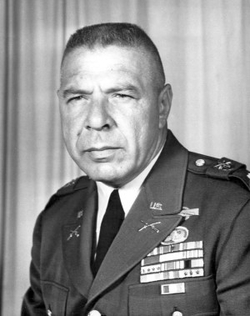

When all other means appeared to be failing, Perot asked Simons to proceed to Tehran with his team. They flew to Iran in mid-January, closely followed by Perot himself, who insisted on overseeing the operation personally and who hoped that his presence would improve the spirits of his jailed employees.

Once in Tehran, Perot and Simons found that nothing worked as they had planned. The Ministry of Justice turned out to be far better protected than anyone had remembered; and anyway, Gaylord and Chiappanrone had been transferred on January 18 to Qasr Prison, one of Tehran's largest and best fortified jails. Though Colonel Simons knew his team could not attack Qasr on its own, he had studied history enough to realize that the revolution was soon going to peak (the Shah had fled Iran on January 16, Khomeni was to return to the country from France on February 1) and that street mobs were likely to storm the prison and release the inmates.

At the same time, EDS kept up its efforts to resolve the problem through legal means. U.S. banks refused to get involved in paying the bail, fearing involvement in matters of bribery and ransom; when one bank finally did cooperate with EDS, matters bogged down on the Iranian side. When all else failed, EDS lawyers went so far as to try to convince Iranian officers to accept the U.S. embassy in Tehran as bail! - rather an ironic suggestion in light of the embassy's subsequent seizure by the Iranian government. All these efforts collapsed on the 10th of February.

Just one day later, Tehran street crowds erupted. Among them was Rashid Kazemi, an ambitious young Iranian trainee systems-engineer at EDS. Loyal to his American employers and eager to help them win the release of their jailed colleagues, Follett describes him as the instigator of the mob's attack on Qasr prison.

These people, Rashid decided, want excitement and adventure. For the first time in their lives they have guns in their hands: They need a target, and anything that symbolizes the regime of the Shah will do.

Right now they were standing around wondering where to go next.

"Listen!" Rashid shouted.

They all listened - they had nothing better to do.

"I'm going to the Qasr Prison!"...He started walking.

They followed him.

Rashid's efforts were successful: Gaylord and Chiapparone fled the jail along with the other prisoners. A few hours later they met at Simons' room at the Hyatt Regency.

As it turned out, however, the escape from prison was much easier than getting out of the country. Without passports and sought by the police, how were Gaylord and Chiapparone to leave Iran? Simons' answer was to divide the remaining EDS employees in Tehran into two groups: the less suspicious were to leave via airplane from Tehran, while the more vulnerable, including the two fugitives, were to go to Turkey in two Range Rovers.

Rashid accompanied the latter group on their 450-mile trip across northwest Iran, far and away the most dangerous part of the entire undertaking. In two long days of driving they repeatedly came close to summary execution; on almost every occasion, it was Rashid's quick wits that saved them. When he and the six Americans finally reached the Turkish border, they were met on the other side by an EDS man waiting with a bus and a charter plane. One day later, February 17, they reached Istanbul, where an anxious Perot had been pacing up and down his hotel room. That the fugitive pair lacked passports and had entered Turkey illegally made even the Turkish portion of the journey somewhat dangerous.

On the same day the overland team reached Istanbul, the other EDS employees left Tehran by plane-barely escaping the same prosecutor who earlier had jailed their colleagues. The two teams met in Frankfurt, Germany, and flew together (via an emergency landing in England) to the United States. All of them, including Rashid , arrived on February 18 to a joyous homecoming.

A straightforward adventure story, On Wings of Eagles nonetheless provokes a number of subtle questions. First, there is the matter of competency: can the author of popular thrillers write history? From a historian's perspective, Follett's writing contains several important flaws.

To begin with, he exaggerates suspenseful and emotional aspects of the story. Chapters end with such cliffhanging phrases as "the cell door clanged shut behind them" or "the nightmare was not yet over." Sentiments are played up on every possible occasion, with the evident intent of tugging at heartstrings. The plight of the men's wives comes up repeatedly, not because this bears on Follett's narrative but artificially to enhance the human interest of his tale. Here, for example, is the account of Bull Simons and Perot's conversation during the homecoming party in Dallas:

Simons bent down and spoke in Perot's ear. "Remember you offered to pay me?"

Perot would never forget it. When Simons gave the icy look you froze. "I sure do."

"See this?" said Simons, inclining his head.

Paul [Chiapparone] was walking toward them, carrying [his daughter] Ann Marie in his arms, through the crowd of cheering friends. "I see it," said Perot.

Simons said: "I just got paid." He drew on his cigar.

The relationship between the author and his subjects poses a second problem. According to the Washington Post, "Perot wanted the story of the rescue told and he had said to his people: Get Follett." Follett's agent and Perot's lawyers then set up a meeting between the two to discuss the project. They hit it off and this book is the result. Is the nearly worshipful treatment of Perot in On Wings of Eagles, then, any surprise? While Perot may in fact deserve it, Follett's indebtedness to him for the story forces the reader to suspect he is reading what journalists call a puff job. In a similar manner, everyone associated with EDS is dealt with utmost delicacy. And Follett himself acknowledges that Perot stipulated that the book be generous to Bull Simons' memory (he died a few months after the Iranian expedition, of natural causes). All this, of course, casts grave doubts on the author's objectivity.

Third, Follett hardly understands what was happening in Iran that precipitated the jailing of Gaylord and Chiapparone, nor does he seem to care. Iran for him is but the backdrop to a stirring story about Americans. Only once in 444 pages does the reader find out what an Iranian revolutionary was thinking about Americans and why he felt hostile to them; most Iranians appear as little more than unpleasant revolutionary automatons. The only sympathetic Iranians are those, like Rashid, who aid EDS against the Iranian government.

Arthur D. "Bull" Simons (1918-79). |

Finally, there is the problem of dialogue. To enliven his narrative, Follett takes the liberty of putting conversational dialogue into the mouths of his characters. Here is his justification:

In recalling conversations that took place three or four years ago, people rarely remember the exact words used; furthermore, real-life conversation, with its gestures and interruptions and unfinished sentences, often makes no sense when it is written down. So the dialogue in this book is both reconstructed and edited. However, every reconstructed conversation has been shown to at least one of the participants for correction or approval.

In short, Follett has written a literary docu-drama, a historical romance about living people - not a history.

In his defense, however, Follett did make a serious effort to uncover the U.S. side of the EDS rescue, and he has written an engrossing account. Even with the advance knowledge of how the mission turns out, I read On Wings of Eagles with single-minded attention. Judged by conventional criteria, Follett's effort is deficient; yet in terms of his own goals, he has entirely succeeded. On Wings of Eagles shot near the top of the best-seller lists soon after publication, and a film is planned.

The rescue mission raises several ethical questions. In the process of freeing Gaylord and Chiapparone, the EDS team forged identity cards, misused passports, and engaged in myriad other illegal acts. Viewed unemotionally, these amount to vigilante justice. Should a corporation assume a government's role when that government fails to protect its citizens? When one remembers that a man like H. Ross Perot - whom Forbes Magazine recently ascribed a personal fortune of over a billion dollars - has greater financial resources at his disposal than a number of sovereign nations, the question takes on added significance. Does the EDS effort presage quasi-military efforts by other multinational corporations? If so, what are the implications?

Follett does not address these issues, and is content to restrict his account to an adventure story. He does portray American officials in a derisory way, reflecting the opinion of the EDS workers. The Department of State comes in for especially rough treatment: "Inept," "Can't organize a two-car funeral," "Disgusted with the State Department," "With friends in the State Department a man had no need of enemies." Foreign Service Officers and politicians seem less evil than incompetent; tied up by red tape and bound by the need to think of U.S. interest on the grand (and therefore impersonal) scale, they lose sight of individual concerns.

Into this void, without hesitation, entered Perot, prepared to act on behalf of the employees he had sent to Iran. It is difficult to do anything but applaud his efforts; yet they set a disquieting precedent. Anyone who might forget how disastrous are the consequences of private militias need only look at the spectacle of Lebanon since 1975.

This said, it must be kept in mind that governments have been the principal perpetrators of crimes in the twentieth century. The lion's share of dispossession, incarceration, maiming, and killing has been done by persons in the employ of governments, acting on behalf of governments. Official violence has surely exceeded that of all other agents combined. Then, too, most rulers currently in power reached office through non-democratic means and maintain their position through repression. Governments so often engage in illegal behavior - as the two American businessmen experienced on a very minor scale - that the active participation of corporations cans serve to protect individuals in many countries.

Were corporations to stand up against governments at times of tension, possibly there would be improvement in some dimensions of the international political scene. (This is particularly the case as corporations are almost exclusively based in those Western countries where the rule of law is most deeply ingrained). As On Wings of Eagles demonstrates, corporations standing up to governments can bring benefits. The question is: to what extent and under what circumstances can such action be condoned?

May 18, 1986 update: The two-part television version of On Wings of Eagles, starring Burt Lancaster, began today on NBC.