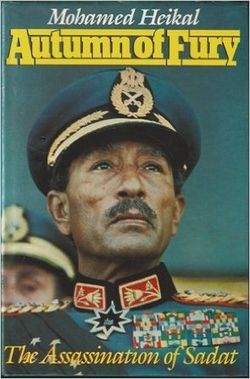

Mohamed Hassanein Heikal, the renowned Egyptian journalist, writes on the first page of Autumn of Fury that he was "very fond of Sadat as a man." The reader might wish to savor these pleasant words, for they are the last he will encounter. Heikal pursues two thoroughly negative themes in this book: that all Egypt's current problems result from President Anwar Sadat's mistaken policies; and that Sadat's assassination in October 1981 followed inevitably from his errors.

Mohamed Hassanein Heikal, the renowned Egyptian journalist, writes on the first page of Autumn of Fury that he was "very fond of Sadat as a man." The reader might wish to savor these pleasant words, for they are the last he will encounter. Heikal pursues two thoroughly negative themes in this book: that all Egypt's current problems result from President Anwar Sadat's mistaken policies; and that Sadat's assassination in October 1981 followed inevitably from his errors.

Heikal condemns every one of Sadat's major policies, including the expulsion of the Russian advisers in 1972, economic liberalization in 1974, and peace with Israel in 1977. His basic difference with the President, however, concerns the aftermath of the war in October 1973. He vehemently disagrees with Sadat's strategy of pursuing a limited war to lay the ground for permanent peace, arguing that this missed a great opportunity. Had Sadat coordinated actions with Syria, Libya, and the oil states, the Arabs would have been in a position to confront Israel. Instead, Sadat "was not really interested in exploiting the initial victories of Egyptian arms, ...what Sadat wanted to do as quickly as possible was to get in touch with the Americans and arrange matters with them." The result, Heikal contends, was a shift toward the United States that did Egypt great harm.

But criticism of Sadat's international policy is less damning than charges relating to domestic affairs. These, drawn from Heikal's insider knowledge of Egyptian politics—he claims to have been "closer to [Sadat] than anyone else ... for the first four years of his Presidency"—touch on virtually every aspect of Sadat's rule. Sadat arrested the loyal opposition and mishandled the growing Islamic and Coptic movements. He tolerated corruption among his family and cronies. He repeatedly took priceless Egyptian antiquities off display at the Egyptian Museum and gave them to foreign friends. Once a year he personally supervised "a bonfire in which all papers he thought would be better forgotten were destroyed"—papers dealing with the disbursement of secret funds and transcriptions of telephone conversations.

These accusations, set out in great detail, constitute the bulk of the book. Here, substantiating the charge that Sadat was self-indulgent and isolated, is an account of the President's daily routine:

He usually woke up late, between 9:00 and 9:30, and on waking would be given a spoonful of mixed honey and royal jelly and a cup of tea. He would read the papers in bed, paying particular attention to al1 the items concerning himself. Then came massage from his personal masseur, some physical exercises, and a bath. This would be followed by a light breakfast, consisting probably of a piece of cheese and some calorie-free toast (all his cereal requirements were made from calorie-free flour imported from Switzerland—even his sweet pastry kunafa). Sadat had found that vodka was a helpful stimulant...two or three vodkas would be taken, so that by 12:00 or 12:30 he was ready for the day's interviews and appointments. After a couple of hours of this he would be complaining of the burden of business ("They are killing me with work") and would adjourn with a friend for perhaps some more vodka, followed by a light lunch of cold chicken or meat and salad. At about 4:30 he would retire to bed and sleep soundly till 7:00 or 7:30, when he would wake hungry. A mint tea would be followed by dinner, ... then there would be talks with some officials or telephone conversations with foreign politicians and Cairo editors. At around 9:00 he would ask to be given a list of films that were available (all films...were sent to the President before being passed to the censor), and by 10:00 he would be watching the first film in his private cinema.

Most of what Heikal writes in Autumn of Fury is new and much of it is damning. But is it true? The absence of documentation—only a handful of footnotes and almost no attributions—makes it impossible independently to verify Heikal's assertions. The credibility of Autumn of Fury depends entirely on the veracity of the author. Is he candid about his objectives or does he have hidden motives? Do his facts match those in the public record and are his judgments trustworthy? For Heikal's charges to stick, he must be above suspicion and his reliability must be established.

He fails both tests. The ostensible purpose of the book is to explain to Westerners the events leading up to Sadat's assassination. But the real purpose is quite different; to revive the memory of Sadat's predecessor, Gamal Abdul Nasser. Heikal rose to prominence as Nasser's personal confidant, and for many years he served as the Egyptian government's spokesman. Today, as the most visible and articulate keeper of the Nasserist legacy, his abiding desire is to reinstate Nasser's reputation and policies.

For this reason, each mention of Nasser in this book is uncritical—no, lyrical: "Nasser achieved so much that he created dreams which were incapable of achievement." Contrary to all evidence, Heikal celebrates Egypt under Nasser as a socialist country "in fact as well as in name." He overstates success (claiming the Aswan Dam was "one of the greatest technological achievements of the age") and breezily dismisses major failures ("Israel and democracy remained his stumbling blocks").

But the key to redeeming Nasser's name is to blacken that of his successor; every act by Sadat is portrayed in the worst possible light. Heikal implies that the abandonment of Nasser's policies of socialism, neutralism, and pan-Arabism explains Egypt's present woes. The economic opening of Egypt in 1974 ended the effort to build a socialist economy and paved the way for maldistribution of income and massive corruption. The rejection of neutralism made Egypt a ward of the U.S., dependent on it for political cues and handouts. The emphasis on Egyptian nationalism led to the loss of Arab support, both economic and political. Because he is building a case, Heikal neglects to mention that Egypt is today less militaristic, more democratic, richer, and freer than under Nasser.

Where others see greatness, Heikal finds fault. Courage and vision had no role in Sadat's decision to go to Jerusalem in November 1977. Rather, this was a political maneuver to escape domestic economic problems, nothing more: "There is a direct link between the food riots in January 1977 and the Jerusalem journey in November." Similarly, Sadat's loyalty to the fallen Shah of Iran is made to look not noble but merely foolish (because it alienated the new regime in Teheran).

Heikal also fails in the matter of accuracy. Those much closer to Sadat than he have categorically denounced this book as unreliable. Hermann Eilts, U.S. ambassador to Egypt from 1973 to 1979, says he found "well over 100 factual errors" in Autumn of Fury. Husni Mubarak, vice president of Egypt through most of Sadat's rule (and now president), said the book includes "events which I myself witnessed. They are inaccurate and untrue. I do not wish to mention the events. I do not like to talk about these topics. I just want to say that they contain untrue stories, far from the truth."

Even persons not privy to the inner councils of Sadat's government can see for themselves the faults of Autumn of Fury, for it distorts matters of public record. Some errors are tangential to the argument: Calorie-free flour? Not even the Swiss can do that. Contrary to what Heikal reports, the Israelis have never demanded the expulsion of the Murabitun militia from Lebanon "on the grounds that they represent a threat to Israel's security." The author contradicts himself from one passage to another. We read on one page that King Hassan of Morocco met the Prime Minister of Israel in April 1977; but two pages later, in the course of describing a meeting in September 1977, Heikal says that "King Hassan had from time to time met Israelis, but never one quite so highly placed as [Foreign Minister Moshe] Dayan."

Major errors abound. In the account of events leading up to the Jerusalem trip, Heikal omits the critical joint U.S.-Soviet statement of October 1, 1977. How can one believe his narrative on less-known matters? He says that Jimmy Carter was "of course delighted" by Sadat's trip; anyone who watched television that day will remember the President's dour reaction as he came out of church. Heikal's description of the Camp David accords is so distorted, the accords are almost unrecognizable: "Egypt was bound to supply Israel with two million tons of oil every year. In return what had the Israelis conceded? Virtually nothing." The return of the Sinai peninsula was "virtually nothing"?

Finally, on matters of interpretation, Heikal displays an extreme political viewpoint. On the one hand, he dismisses as "an implausible story" documented accounts of Mu'ammar al-Qaddafi's wanting to assassinate Sadat. On the other hand, he seriously considers the notion that the CIA arranged for Sadat's assassination, deciding against this explanation only because "Sadat's regime was still able to serve American interests in the Middle East." Heikal implies that Qaddafi would never dream of killing Sadat, while Ronald Reagan would do away with him as soon as he had outlived his usefulness. This sort of attitude gives one little confidence in the author.

Along similar lines, Heikal argues that "the forces which conspired against Sadat were just as much a part of the mainstream in Egyptian society as were the forces which overthrew the Shah from the mainstream in Iran." Heikal thus equates a nationwide movement that included millions of people with what he himself calls a conspiracy of four isolated and violent fanatics, operating in darkest secrecy. In his effort to condemn everything associated with Sadat, Heikal ends up justifying any force that opposed him, even his killers.

A polemic written with the single-minded purpose of destroying a man's reputation cannot be relied upon as biography. Parts of Autumn of Fury may be true, to be sure, but how can the reader tell which ones? Rather than guess mistakenly, he would do better to ignore Mohamed Heikal's angry testimony and await a more solid account.

Oct. 7, 2015 update: Over thirty years later, this review prompted an article by Hala Amin in Al-Bawaba.

Feb. 17, 2016 update: Heikal, the last prominent Nasserist, is dead at 92, 46 years after Nasser himself.