A century back, travelers wrote many of the books about the Middle East published in the United States. They had a formulaic quality: the voyager visits the great capitals of the regions (Istanbul, Cairo) on his way to Jerusalem; he is dismayed and appalled by the living conditions of the natives; he returns safely home, wiser and better for his efforts. Whatever their limitations, those travel accounts had the triple virtue of usually being informative, well-written, and interesting.

A century back, travelers wrote many of the books about the Middle East published in the United States. They had a formulaic quality: the voyager visits the great capitals of the regions (Istanbul, Cairo) on his way to Jerusalem; he is dismayed and appalled by the living conditions of the natives; he returns safely home, wiser and better for his efforts. Whatever their limitations, those travel accounts had the triple virtue of usually being informative, well-written, and interesting.

Today, the amateur traveler to the Middle East no longer has a market for his tales. Instead, the professional journalist has replaced him. Oddly, the new genre resembles the old one in several ways. It is intended to edify and entertain the homebound reader. It too contains local color and pithy conversations. It has a formulaic quality, mixing original materials (interviews and personal impressions) with second-hand materials (potted histories, political analyses).

But the new genre is much tougher to pull off, and only a few outstanding writers manage to do so. V. S. Naipaul wrote a classic of the type in his 1981 book, Among the Believers. Thomas L. Friedman succeeded in his best-selling From Beirut to Jerusalem of 1989. But most efforts fail. Jonathan Randal's 1983 account, Going All the Way: Christian Warlords, Israeli Adventurers, and the War in Lebanon is just as bad as its title intimates. Charles Glass wrote perhaps the very worst of the type in his 1990 Tribes With Flags.

Now Milton Viorst, a reporter who has traveled in recent years to the Middle East for The New Yorker, tries his hand as a journeying journalist. He fares little better than Randal or Glass. To be sure, his Sandcastles shows flickers of competent journalism. He can snag the startling quotation (a Gazan told him "The Arabs say they're our friends, and treat us worse than the Israelis do") and he can write incisively (President Hafiz al-Asad of Syria is a man for whom "an air of enigma is an instrument of state"). But the odd insight does not save a book chock-full of pretension, factual mistakes, cultural incomprehension, and political bias.

The pretension starts with the subtitle: somehow, Viorst flatters himself into believing that a few trips to the Middle East and some interviews with big shots gives him a base for interpreting the Arab experience with modernity. Not for him is it necessary to slog through the many scholarly analyses of this very question, live in the region, or devote years studying the Arabic language. Well, it hardly needs stressing that Viorst's thinking on this subject is as superficial as it is derivative.

As for errors of fact, Viorst gets ancient history wrong (misnaming, for example, one of the Prophet Muhammad's grandsons as Abbas; he was actually Hasan). His current history is yet more of a fiasco. Jimmy Carter enunciated the Carter Doctrine not in 1981, as Viorst states, but in 1980; Abu Musa's rebellion against Yasir Arafat took place not in 1982 but in 1983. Iraqi troops famously invaded Kuwait not on August 1, 1990, but on August 2. Ba'th Party doctrine does not include Kurds, only Arabic speakers.

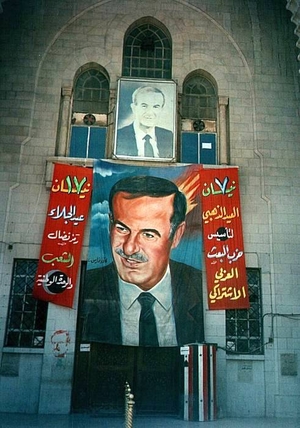

A typical sight in Syria. |

Sandcastles contains illogical passages. We learn on one page that Asad has faced no challenge to his rule since 1970; seven pages later, Viorst reports on the carnage at Hama in 1982 that resulted from precisely such a challenge. On page 330, Viorst tells us that Iraqis openly criticized Saddam in the spring of 1991; two paragraphs later he observes that Iraqi fear of the secret police then remained as great as ever. Does this author ever reread his notes?

Though he treads light on politics, Viorst betrays an all-too-familiar outlook throughout his account: stick it to America's allies, portray our opponents favorably. His chapter on Turkey (not usually known as an Arab country, but included here anyway) bristles with antipathy. He describes Istanbul (in an ungrammatical flourish) as a "melancholy city" and exploits the bad weather during his visit as a metaphor for Turkey's unattractiveness. In Kuwait, Viorst magnifies every foible of the ruling family and dwells lovingly on the faults of the population. Israel, of course, he blames for the decades of Arab-Israeli conflict. Revealingly, he relates his efforts to convince Kuwaitis not to be so angry with Palestinians who sympathized with Saddam Hussein. It wasn't so much that they hated Kuwait, he explained to them, as they nursed a grievance against what he calls "America's long-standing preference for Israel over their own cause."

This comment speaks volumes about Viorst's views on the Middle East. It also points to another hackneyed, distasteful theme: blame America. Viorst dismisses as "surely an oversimplification" the notion that Saddam Hussein's evil character caused the Kuwait Crisis. He prefers another, overly complex explanation that blames the U.S. government. (His argument has something to do with Washington signaling Kuwaitis that it would back them if they got into trouble with Iraq by overproducing oil.) But the passage which most pungently sums up the author's hopelessly trendy political views is the one in which he tells us how Saddam Husayn reminds him of Richard Nixon! Anyone who draws this comparison automatically disqualifies himself as my guide to "the Arabs in search of the modern world."

Actually, not that much has changed since the nineteenth century; as in Mark Twain's day, we're still sending innocents abroad.

Sep. 1, 1998 update: For another review of a Viorst book, click here.

Dec. 17, 2022 update: The New York Times obituary of Milton Viorst treats his oeuvre with undo kindness.