Thank you, John, and good morning, Ladies and Gentlemen. I've been trying to get John to come to my organization and speak, and now I feel I've got a quid pro quo. I cordially invite you, as previously intended.

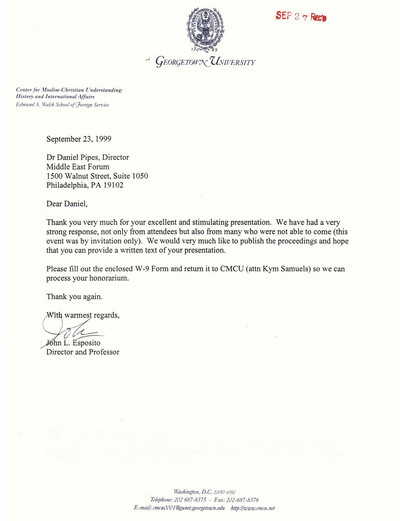

View the full-size version of John L. Esposito's note of appreciation for Daniel Pipes' talk. |

Our title today suggests a discussion of Islam, but this can not be, for there is no American government policy toward religion, either Islam or any other. In fact, the topic is Islamism, which the government does have a policy toward.

There is a great difference between Islam and Islamism. To put it most succinctly, they represent faith versus ideology. Islam is a religion of some fourteen centuries' antiquity, or, in the Muslim view, even older. Islamism is an ideology of the 20th century, one that, to be sure, has its roots in earlier writings and thinking, but one which very much a contemporary phenomenon, a response by modern people to modern problems. Islamism is also a political movement; and therefore a political response by the US government to it is completely appropriate. As the only cohesive and virulent body of anti-American ideas active in the world today, it naturally attracts considerable U.S. attention.

I take issue with Ambassador Djerejian's notion that Islamism results from social injustice; in my view, it has to do with much larger issues of identity. To sum up a large and complex argument in just a few words, the Muslim world of the past two centuries has undergone a trauma, one resulting from the contrast of the extraordinary record of the medieval period, when Muslims were leaders in many areas of human endeavor, with the many problems of today, when Muslims have generally fallen behind in those same areas. The symbolic turning point was Napoleon's conquest of Egypt in 1798; the two hundred years since then have been, broadly speaking, a time of tribulation, of trying to figure out what went wrong. The frustration is intense: Muslims feel they should be strong but find themselves weak. Many thinkers and politicians over the past two centuries have tried to explain this predicament and offer a way out. Islamism is one such answer. It both explains the decline (not living enough by the law of Islam) and it offers a solution (live by it).

Islamism has to do with one's sense of being a Muslim and what that should translate into in terms of power and wealth relative to non-Muslims. It has little to do with specific problems of social injustice or economic deprivation. There are plenty of cases in which people who have been subject to injustice or impoverishment have not turned to Islamism (think of Iraq under Saddam Husayn or Iran under the mullahs).

Islamists are deeply defensive, trying to preserve an Islamic way of life; but as so often happens, such fears transmute into bellicosity. In particular, Islamists are profoundly anti-American, for the United States - with its individualism, consumerism, and exuberant popular culture - represents all that they battle against. Islamists greatly fear that the United States, with its glamour and its many attractions, will distract people away from the True Path of Islam; they see this country as the great seducer. Note that culture, more than power, is the problem. As the Ayatollah Khomeini once said, "We are not afraid of economic sanctions or military intervention. What we are afraid of is Western universities." Note also that he is not talking about hamburgers or blue jeans, but about universities, which more generally represent high culture. Western high culture threatens Islamists no less than does the much more visible forms of low culture.

What do Islamists want? To take power and dominate everyone else, Muslim and non-Muslim. By its very nature, theirs is a very aggressive outlook. Even the United States is not free from this ambition; some Islamists freely acknowledge their desire to take power here; the explosion at the World Trade Center in New York was a symptom of this outlook. Despite this, it bears emphasis that Muslims who reject the Islamist message tend to be the first and most numerous victims of Islamism. In the words of a prominent Turkish general, Islamism is for them "public enemy number one."

I see Islamism as a radical utopian movement very much in the image of other such movements of the 20th century. It represents an Islamic-flavored version of totalitarianism. Professor Esposito distinguishes between moderate and extremist Islamism, but this taxonomy does not convince me. I see in this mere differences in tactics, not in goals. Totalitarians who use the ballot box are in the end hardly different from those who use violent means. Was Hitler less of a threat than Stalin?

The notion has been raised here that in about 1991-92, a search began in the United States for a new enemy to replace the fallen communist bloc. But I've yet to hear of anyone who said, "Okay, the cold war is won, who is the next enemy? Red is finished; now let's turn to green." What happened, rather, was a new assessment of American interests around the world and the discovery that Islamism poses a real threat to American interests. Nor did this issue appear overnight. I, for one, am on the record in a 1985 article in Foreign Affairs, a time when the Cold War was still very active, writing that Islamism is a problem, and we have to adjust American foreign policy to it.

Turning to American policy, I suggest five steps:

First, support those states-Muslim and not-which are taking the brunt of the Islamist threat. The U.S. has other priorities, of course, but one of them is holding back an international ideology that targets us. Certainly, the abortion of the democratic process in Algeria is something one doesn't endorse in any way happily, but I think it was necessary for the reasons that Ambassador Djerejian alluded to: because an Islamist takeover would have spelled the end of the democratic process that has in fact emerged in subsequent years.

Second, pressure Islamist states, particularly Iran, Afghanistan, and Sudan, to reduce their aggressiveness towards their neighbors, towards their people, and towards the United States.

Thirdly, label those groups and movements that are Islamist and engage in violence as what they are, namely terrorist organizations, then work to defeat them.

Fourthly, avoid cooperation with such Islamist movements and states. Obviously at times one has to cooperate with them, but this should be minimal. Understanding who the main threat is at times means entering alliances that offend. Just as Washington during the cold war maintained alliances with less-than-savory regimes that were anticommunist, the realities of international politics today require a similar effort against Islamism.

And finally, on a positive note, we should promote civil society, not elections. Experience shows (most dramatically in Algeria) that if a government holds snap elections, Islamists can do very well, for they alone have an organization already in place. Therefore we should see elections not as the beginning of a process, but its capstone. Begin with the long process of building civil society-voluntary institutions, the rule of law, minority rights, property rights, and the like. Only after the gradual development of civil society does the proper basis for elections exist.

In brief, we should not talk about Islam, but Islamism, which is as a serious problem for the United States, and we should take a strong and intelligent stand against this virulent new form of totalitarianism.