The eminent historian Niall Ferguson has devastatingly skewered his (and my) field of study in a talk for the American Council of Trustees and Alumni, subsequently published as "The Decline and Fall of History."

He starts with the empirical fact that undergraduates are running away from studying history: compared with 1971 (coincidentally, the year I got my A.B. degree), "the share of history and social sciences degrees has halved, from 18% in 1971 to 9%. And the decline seems likely to continue."

Niall Ferguson delivering ACTA's Merrill Award at the Folger Shakespeare Library on Oct. 28, 2016. |

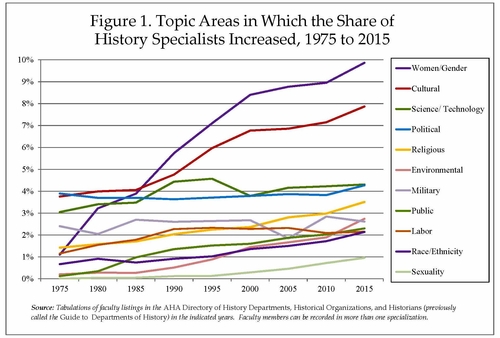

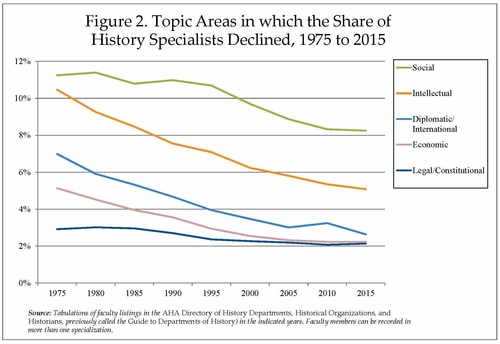

Why so? Data from the American Historical Association finds that the past 40 years have seen

a very big increase in the number of historians who specialize in women and gender, which has risen from 1% of the total to almost 10%. As a result, gender is now the single most important subfield in the academy. Cultural history (from under 4% to nearly 8%) is next. The history of race and ethnicity has also gone up by a factor of more than three. Environmental history is another big winner.

The losers in this structural shift are diplomatic and international history (which also has the oldest professors), legal and constitutional history, and intellectual history. Social and economic history have also declined. [Almost] all of these have fallen to less than half of their 1970 shares of the profession.

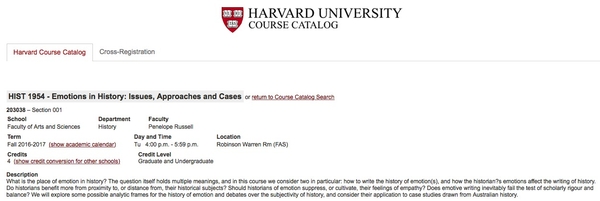

This means that the most significant events are ignored. Limiting oneself to modern Western history, courses barely cover such topics as the French Revolution, the Industrial Revolution, World War I, World War II, and the Cold War. Instead, one encounters a course such as Harvard's History 1954: "Emotions in History" whose course description reads:

What is the place of emotion in history? The question itself holds multiple meanings, and in this course we consider two in particular: how to write the history of emotion(s), and how the historian's emotions affect the writing of history. Do historians benefit more from proximity to, or distance from, their historical subjects? Should historians of emotion suppress, or cultivate, their feelings of empathy? Does emotive writing inevitably fail the test of scholarly rigour and balance? We will explore some possible analytic frames for the history of emotion and debates over the subjectivity of history, and consider their application to case studies drawn from Australian history.

Ferguson reports the "not wholly surprising" fact that "Emotions in History" boasts a total enrollment of one student. Yale competes with its own offerings such as "Witchcraft and Society in Colonial America" and "History of the Supernatural."

Ferguson delicately asserts that he does "not wish to dismiss any of these subjects as being of no interest or value. They just seem to address less important questions than how the United States became an independent republic with a constitution based on the idea of limited government."

Not only does this new type of history take on minor concerns but it deals with them in miniature ways that amount to what a student dubs "heirloom antiquarianism" and Ferguson calls Microcosmographia Academica – focusing on topics like "the habits of New York restaurant-goers in the 1870s or the makeup of various Caribbean ethnic groups in areas of Brooklyn that made up the West Indian Day Parade in the 1960s" (real examples).

Not only does this new type of history take on minor concerns but it deals with them in miniature ways that amount to what a student dubs "heirloom antiquarianism" and Ferguson calls Microcosmographia Academica – focusing on topics like "the habits of New York restaurant-goers in the 1870s or the makeup of various Caribbean ethnic groups in areas of Brooklyn that made up the West Indian Day Parade in the 1960s" (real examples).

Finally, there's the politicizing, moralizing, and anachronistic insistence on judging "the past by the moral standards of the present—and indeed to efface its traces, in a kind of modern-day iconoclasm, when these are deemed offensive."

In all, as historians "neglect the defining events of modern world history in favor of topics that are either arcane or agitprop, sometimes both," students flee and the "United States of Amnesia" looms.

Bravo to Niall Ferguson for pointing out the hollowing out of a once-great field of study. (April 4, 2017)

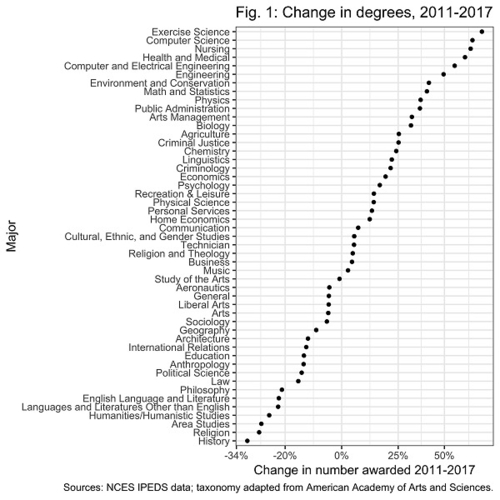

Nov. 26, 2018 update: Benjamin M. Schmidt reports in "The History BA since the Great Recession" a decade ago that "Of all the major disciplines, history has seen the steepest declines in the number of bachelor's degrees awarded." A graph makes this point starkly.

Looking at history degrees as a percentage of all college-age adults in the United States, the level has gone down from 11.8 degrees per 1,000 in 1971 to 5.3 in 2017. Schmidt blithely dismisses this collapse as "anxiety over career prospects for history majors," which he considers unfounded given "that students with history BAs disperse into a wide variety of careers."

Dec. 10, 2018 update: "The Historical Profession Is Committing Slow-Motion Suicide" write Hal Brands and Francis J. Gavin. Their analysis overlaps with Ferguson's except that they focus more on history's decreasing relevance to statecraft.

They start by noting that about 1/5th the number of students now study history in college compared to the late 1960s. Why is this?

The discipline mostly has itself to blame for its current woes. In recent decades, the academic historical profession has become steadily less accessible to students and the general public — and steadily less relevant to addressing critical matters of politics, diplomacy, and war and peace. It is not surprising that students are fleeing history, for the historical discipline has long been fleeing its twin responsibilities to interact with the outside world and engage some of the most fundamental issues confronting the United States.

The rest of the essay looks at these two problems. On the first:

Consider the first of these issues: the retreat of scholarly history from the public square. There was a time when academic historians actively engaged in shaping policy on the critical issues of the day, and when the top academic historians wrote for a larger public audience. Woodrow Wilson engaged the country's leading diplomatic historians to help him prepare for the Versailles Peace conference. Eminent scholars such as William Langer, Arthur Schlesinger, Ernest May, and Richard Pipes served in or consulted with government while retaining their academic positions during the Cold War. Schlesinger, Daniel Boorstin, C. Vann Woodward, and Richard Hofstadter wrote widely read books that drove public debate on issues such as political reform, populism, McCarthyism, and the broader American political tradition.

Yet as the historical discipline (like much of the American academy) became more professionalized, especially after World War II, it also became more specialized and inward-looking. Historical scholarship focused on increasingly arcane subjects; a fascination with innovative methodologies overtook an emphasis on clear, intelligible prose. Academic historians began writing largely for themselves.

On the second, hostility toward certain kinds of historical inquiry:

Decades ago, the subfields of political history, diplomatic history, and military history dominated the discipline. That focus had its costs: Issues of race, gender, and class were often deemphasized, and the perspectives of the powerless were frequently ignored in favor of the perspectives of the powerful. During the 1960s and after, the discipline was therefore swept by new approaches that emphasized cultural, social, and gender history, and that paid greater attention to the experiences of underrepresented and oppressed groups. This was initially a very healthy impulse, meant to broaden the field. Yet what was initially a very healthy impulse to broaden the field ultimately became decidedly unhealthy, because it went so far as to push the more traditional subfields to the margins. ...

This cartoon did once make sense. Not so much anymore.

academic historians simply are not focusing their efforts on some of the issues that matter most to the fate of the United States and the international system today. Instead of possessing deep historical knowledge that serves as the intellectual foundation for effective policy and informed debate, the nation risks worsening historical ignorance with all its attendant dangers. ... if the United States does not reinvest in the traditions that academic history departments have left behind, declining undergrad enrollments will be the least of the country's problems.

Aug. 12, 2025 update: Patryk J. Babiracki, an associate professor of history at the University of Texas at Arlington, offers "A Plan to Rebuild History's Brand." His subtitle explains that "Our departments don't have a problem with substance. We have a problem with storytelling." Not a word in his analysis about the problems raised above.