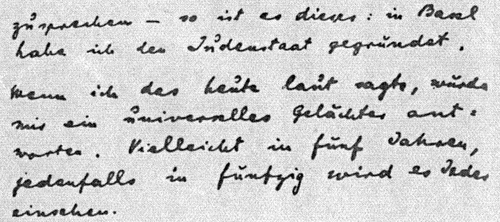

Theodor Herzl (1860-1904) wrote in his diary on Sep. 3, 1897, three days after the close in Basel of the Zionist Organization's First Zionist Congress that he had chaired:

in Basel habe ich den Judenstaat gegründet. Wenn ich das heute laut sagte, würde mir ein universelles Gelächter antworten. Vielleicht in fünf Jahren, jedenfalls in fünfzig wird es jeder einsehen.

(at Basel, I founded the Jewish State. Were I to say this in public today, I would be greeted with universal laughter. Perhaps in five years, in any case in fifty, everyone will see [the truth of] this.)

The above quote starts with the final two words of the top line. |

Fifty years later to the day, on Sep. 3, 1947, the United Nations Special Committee on Palestine (UNSCOP) presented its Report to the General Assembly calling for the end of the British Mandate and proposed a Plan of Partition of Palestine into a Jewish state and an Arab state.

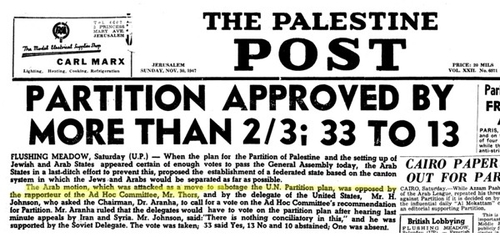

On Nov. 29, 1947, the UN General Assembly passed UNSCOP's plan almost without changes as Resolution 181, thereby formally recognizing "the Jewish State" that Herzl had foreseen.

The "Palestine Post" reported the General Assembly vote lacking a sense of its historic importance. |

This extraordinary prediction comes to mind on the 120th and 70th anniversaries of the two dates. (September 3, 2017)

Sep. 3, 2017 addenda: (1) And the all-time worst prediction? Perhaps that of the British Cabinet's only Jewish member, Edwin Montagu, writing to it on Mar. 16, 1915:

Palestine in itself offers little or no attraction to Great Britain from a strategical or material point of view ... [It is] incomparably a poorer possession than, let us say, Mesopotamia ... I cannot see any Jews I know tending olive trees or herding sheep ... There is no Jewish race now as a homogenous whole. It is quite obvious that the Jews in Great Britain are as remote from the Jews in Morocco or the black Jews in Cochin as the Christian Englishman is from the moor or the Hindoo.

(2) Other brilliant predictions?

— Desiderius Erasmus, writing in a letter from Antwerp to Thomas, Cardinal of York, on Sep. 9, 1517: "In this part of the world I am afraid a great revolution is impending." Martin Luther began the Protestant movement on Oct. 31, 1517.

— Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America (1835), chapter 18:

The time will therefore come when one hundred and fifty million men will be living in North America, equal in condition, all belonging to one family, owing their origin to the same cause, and preserving the same civilization, the same language, the same religion, the same habits, the same manners, and imbued with the same opinions, propagated under the same forms. The rest is uncertain, but this is certain; and it is a fact new to the world, a fact that the imagination strives in vain to grasp.

There are at the present time two great nations in the world, which started from different points, but seem to tend towards the same end. I allude to the Russians and the Americans. Both of them have grown up unnoticed; and while the attention of mankind was directed elsewhere, they have suddenly placed themselves in the front rank among the nations, and the world learned their existence and their greatness at almost the same time.

All other nations seem to have nearly reached their natural limits, and they have only to maintain their power; but these are still in the act of growth. All the others have stopped, or continue to advance with extreme difficulty; these alone are proceeding with ease and celerity along a path to which no limit can be perceived. The American struggles against the obstacles that nature opposes to him; the adversaries of the Russian are men. The former combats the wilderness and savage life; the latter, civilization with all its arms. The conquests of the American are therefore gained by the plowshare; those of the Russian by the sword. The Anglo-Americans relies upon personal interest to accomplish his ends and gives free scope to the unguided strength and common sense of the people; the Russian centers all the authority of society in a single arm. The principal instrument of the former is freedom; of the latter, servitude. Their starting-point is different and their courses are not the same; yet each of them seems marked out by the will of Heaven to sway the destinies of half the globe.

— Sergei Witte, a top Russian politician, predicting in 1905 what a revolution in Russia would look like:

The advance of human progress is unstoppable. The idea of human freedom will triumph, if not by way of reform then by way of revolution. But in the latter event it will come to life on the ashes of a thousand years of destroyed history. The Russian bunt [rebellion], mindless and pitiless, will sweep everything, turn everything to dust. What kind of Russia will emerge from this unexampled trial surpasses human imagination: the horrors of the Russian bunt may exceed everything known to history. It is possible that foreign intervention will tear the country apart. Attempts to put into practice the ideals of theoretical socialism - they will fail but they will be made, no doubt about it - will destroy the family, the expression of religious faith, property, all the foundations of law.

— Neguib Azoury in 1905 on the Arab-Jewish battle ahead:

Deux phénomènes importants, de même nature et pourtant opposés, qui n'ont encore attiré l'attention de personne, se manifestent en ce moment dans la Turquie d'Asie : ce sont, le réveil de la nation arabe et l'effort latent des Juifs pour reconstituer sur une très large échelle l'ancienne monarchie d'Israël. Ces deux mouvements sont destinés à se combattre continuellement, jusqu'à ce que l'un d'eux l'emporte sur l'autre. Du résultat final de cette lutte entre ces deux peuples représentant doux principes contraires, dépendra le sort du monde entier.

(Two important phenomena, of the same nature but opposed, which have attracted nobody's attention, are emerging at this moment in Asiatic Turkey. They are the awakening of the Arab nation and the dormant effort of the Jews to reconstitute the ancient kingdom of Israel on a very large scale. These two movements are destined constantly to confront each other until one of the two prevails over the other. On the final outcome of this struggle between two peoples representing two contrary principles will depend the destiny of the entire world.)

— Ferdinand Foch, the Supreme Allied Commander in World War I, on the Treaty of Versailles of June 28, 1919:

This is not peace. It is an armistice for twenty years.

World War II in Europe began days after the twenty-year mark had passed, on Sep. 1, 1939.