It all started when I read anguished complaints in the Kuwaiti press in late 1985. These made no sense at the time: how could it be that American officials were pressuring the Kuwait government to release convicted terrorists, contradicting everything that was then known about United States policy? Unable to figure out what to make of these reports, I filed them away.

A year later, of course, they made good sense. When the U.S. arms-for-hostages deals with Iran became public, I retrieved the Kuwaiti reports and published an article in The Wall Street Journal telling how the United States government had tried to spring convicted terrorists. The article also noted that the Kuwaiti authorities had resisted our efforts as well as a wide range of terrorist challenges - including an attack on their oil facilities and an attempt to assassinate the Kuwaiti ruler.

I compared Kuwaiti actions favorably with the empty bluster about terrorism coming from U.S., Israeli, and West European authorities - all of whom had recently appeased terrorists. The article ended saluting the true Arab honor of the Kuwaiti emir. The newspaper column added some new information to the arms-for-hostages scandal and sought to make known that at least one government had stuck by its principles.

It had not occurred to me that Kuwaitis would take note of the piece. But they did; it became the leading news item in Kuwait a few days later. For example, As-Siyasa had a banner headline across the front page, "Emir Jaber Only Ruler Refusing Deal With Terrorists: Stand Represents True Arab Honor." Other papers followed suit.

As a Washington Post report put it, "Accounts of the column reverberated on state-run television and radio for two days while minimal official notice was taken of President Reagan's personal letter to Emir Jaber Sabah." This gave me a chuckle; abuse us as they may, foreign governments continue to set great store by the views of Americans.

I filled these clippings away as a curiosity and forgot the incident. It came as a surprise, to say the least, when a letter from the Kuwait ambassador in Washington arrived, inviting me to visit Kuwait as a guest of the Minister of Information. Long curious to see this country, I accepted.

Traveling from the United States, one reaches Kuwait from the northwest, across the huge and absolutely uninhabited Arabian desert. After two hours of seeing nothing but blank terrain, only in the last seconds before touchdown do the blue sea and the angular irregularities of a brand new city turn up. From the sky, the city appears gray, formless, and anonymously modern.

Kuwait City "appears gray, formless, and anonymously modern." © Daniel Pipes |

Driving through Kuwait City (where 90 percent of Kuwait's residents live) confirms this impression. The town is extremely new and uncharacterful. The roadways are enormous, efficient, and clean; the stores, brightly lit and modern. Virtually every trace of the older buildings, city walls, and roads has been obliterated. Anything more than twenty years old counts as antique. To imagine Kuwait, purge your thoughts of bazaars, citadels, and narrow roads; this place resembles Houston much more than the ancient cities of the Middle East. Actually, the similarity of the two goes beyond architecture and city planning: Kuwait shares with Houston a scorching climate and an almost complete absence of evident history. Both rose with the oil boom of the 1970s and both suffer from the glut of the '80s.

What is of real interest in Kuwait - and what makes it so different from Houston - is its population. Geography and history pale beside the unique economic and social life of Kuwait. What Balzac called the human comedy is seen here in one of its oddest forms. The Kuwaitis are a people who until the 1940s lived in a small world delineated by Islam, the desert, pearl diving, fishing, and a bit of trade. The country was a backwater, a poor and simple place with little to offer the industrialized world and hardly influenced by it. Then oil suddenly thrust Kuwaitis into the vortex of the world economy, made them rich, gave them power, and deluged them with Western culture.

I expected Kuwait to be a dull, parasitical society, where foreign workers do all the work, citizens lounge in decadent luxury, and nothing serious happens. My expectations were not entirely wrong, but the country is surprisingly interesting and attractive.

The first thing to know about Kuwait, of course, is that it has an immense reserve of oil under its sands. Those reserves are presently estimated at 10 million metric tons, the second largest after Saudi Arabia's 16 million tons. (In contrast, the United States has only 4 million tons.) The other thing to know is that the non-Kuwaitis explore, drill, refine, transport, and consume this oil. Kuwaitis contribute little but raw material to the industry that sustains them.

From a distance, I expected the unearned quality of Kuwait's money, which influences every aspect of life there, to permeate the country's consciousness as well. It came as a real surprise to learn that Kuwaitis almost forget this fact. A swirl of activity - the war to discuss, business to transact, parties to attend, consumer items to enjoy - makes the artificiality of their affluence a distant and rather theoretical point. Were a visitor to arrive in Kuwait not knowing the source of the country's wealth, he might not catch on for weeks or months.

The demographics of Kuwait are unusual, to say the least. Citizens number only 600,000; expatriate laborers total twice that number. Recent figures indicate that 82 percent of the work force is foreign; even among government employees (the favorite occupation of citizens), two-thirds are foreign. Further, citizens keep easy work hours; in theory, offices are open from 7:30 a.m. to 1 p.m., when they close for the day, but I never got an appointment before 10 a.m.

Le Meridien Kuwait. © Daniel Pipes |

Having Kuwaiti citizenship is tantamount to being an aristocrat. What Aristotle wrote about every man needing a slave applies to Kuwait, except that every man, woman, and child in fact has two servants. Citizens exude a sense of well-being and superiority, of confidence and ease in command. These are people who are used to giving orders and getting the best.

Kuwait is the ultimate rentier society. Unlike the other OPEC members, which still depend on oil sales for income, the Kuwaitis have salted away so much, they now derive more from investments than from oil revenues. This allows them to endure the downturn in oil revenues better than other exporting states. Never before in human history has an entire population depended financially primarily on investments. Never before has a whole country enjoyed the benefits of wealth before learning the skills that created that wealth. One can look at Kuwait as a very expensive experiment for social scientists to study; even better, as a unique creation waiting to be explored and explained by novelists.

Kuwait has a real, if discreet, political life which centers in the traditional institution called the diwaniya. Any man with the means can build himself a diwaniya, a large room with chairs and sofas around the edges where he most evenings holds an open house for male Kuwaiti citizens. The crowd a diwaniya attracts depends on the standing of the host. Gossip, jokes, story-telling, and deal-making take up much of the time, but politics is the pervasive theme. The diwaniyas are the courts of public opinion in Kuwait. They have, of course, no official standing and no power, but they do provide a mechanism of transfer for information. And in a society of aristocrats, surrounded by predatory neighbors and out-numbered by aliens, this opinion seems to count.

Paula and Daniel Pipes at a meeting with Kuwaiti officials. |

I left Kuwait with two dominant impressions. First, enormous wealth permits Kuwaitis to enjoy an unusual degree of confidence toward Western civilization. In this, they resemble the Japanese. Never mind that Japan got where it is through indigenous effort and Kuwait got it all from payments for oil; the result is similar. Both are free to choose on their own terms what they like from the West; absent is that sense of persistent pressure that so afflicts the poor countries. The result is a confidence, a fluency in moving back and forth between cultures, and an easy openness towards Westerners.

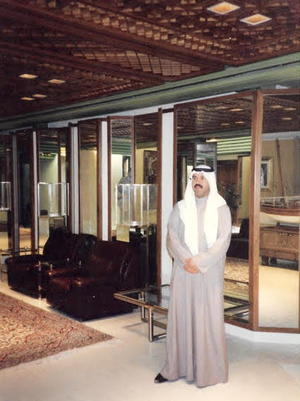

How Kuwaiti men dress. © Daniel Pipes |

Second, the visit revealed to me why generations of Britons and Americans have found societies of the desert seductive. This had never been apparent to me from three years of living in Cairo, a much more profound but at the same time a far more Westernized city. The Bedouin have an open hand and an upper-class demeanor that contrasts strikingly with the hum-drum of democratic ways. Rulers dispense generosity in a style reminiscent of the Thousand and One Nights. The old saw about the American who told the sheikh how much he admired the sheikh's golf clubs - and then received not a bag of golf clubs but the deed to an 18-hole golf club - hardly seems like an exaggeration.

My host, the minister of information, is a member of the ruling family (they avoid the term "royal" in Kuwait) and a potential ruler of the country. Known as Sheikh Nasir, he is an outgoing and energetic aristocrat - the very model of an Arabian leader. He arranged for everything with a lavish hand: car, driver, and escort the whole time, a full schedule of meetings with cabinet ministers and other notables, invitations to public and private parties. The sheikh hosted a grand Bedouin-style lunch for me in the desert and then heaped gifts at my departure.

Paula and Daniel after "a grand Bedouin-style lunch" in Kuwait. |

On a more mundane level, the typical formal dinner I attended (for men only, of course) offered ten times more food than could possibly be consumed; as a result, half the dishes returned to the kitchen untouched. Those of us who trudge to the grocery store every week cannot help but feel an exaltation at this extravagance.

The ultimate question to ask about Kuwait and the other oil-exporting countries is: What have they to show for the hundreds of billions of dollars extracted at great pain from much of the world's population? What are they doing in return? Is there anything that will benefit mankind?

So far, the results are meager. The achievement amounts to making the good life available in one of the most inhospitable regions on the earth. Goods are snapped up from the ultra-fashionable luxury stores with branches in Rome, New York, and Kuwait. Food comes from, among other places, New Zealand, the Sudan, France, and Argentina. Air conditioning is ubiquitous. There are more cars with telephones here than in Manhattan.

But is there anything beyond the fine buildings, the brand names, and the servants? Yes. There are ambitions to accomplish something, to have a constructive role. Efforts include a university, an institute for scientific research, a museum, a hospital specializing in Islamic medicine (whatever that may be - no one could explain the concept to me), and the like. Education has flowered; it came as a surprise to me, but Kuwait has some learned and very sophisticated intellectuals. Indeed, with the demise of Lebanon, Kuwait has become an important cultural center for all the Arabic-speaking countries. The best of the Middle East drifts to the oil-producing states for work, interesting foreign visitors pass through, and many citizens travel abroad. The most-widely read Arabic magazine, Al-'Arab, comes from Kuwait and the Arabic version of Sesame Street originates here.

Although consumerism prevails, there is a chance - a much better chance than I would ever have guessed from a distance - that something worthwhile will come of this very expensive experiment.

Daniel Pipes, author of In the Path of God: Islam and Political Power (Basic Books), is director of the Foreign Policy Institute in Philadelphia and editor of Orbis, its quarterly journal.