"On or about December 1910, human character changed," wrote British novelist Virginia Woolf in 1924. "I am not saying that one went out, as one might into a garden, and there saw that a rose had flowered, or that a hen had laid an egg. The change was not sudden and definite like that. But a change there was, nevertheless."

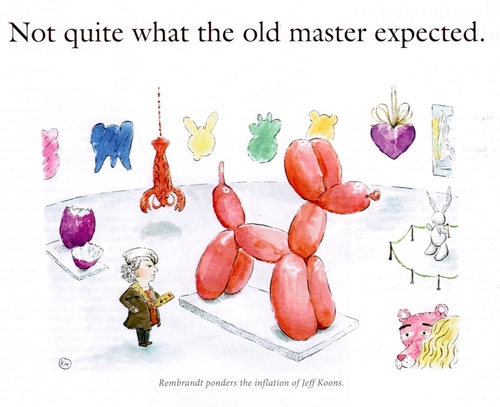

Woolf's famous quote refers specifically to an exhibition of naturalist paintings. More broadly, 1910 marked the approximate date of a huge shift in the world of art: out went the traditional goal of creating beauty, replaced by the modernist goal of promoting ideals and imparting a political message, especially one that would épater la bourgeoisie (shock the middle class). Toward this end, rudeness and ugliness is inherent to the progressive goal of irritating, disturbing, and teaching.

Italy, home of the Renaissance, widely considered to be the apogee of artistic achievement, offers a striking place to observe this contrast, as my recent travel to twelve Italian towns brought home.

Since the Grand Tour began in the seventeenth century, the traveler's dominant experience in Italy has been to go and immerse oneself in its beauty. In part, it's the country's natural attractions, from rolling hillside vineyards to dramatic seaside vistas. But mostly it's the Italians' artistic accomplishments: Roman statuary and ruins, Renaissance piazzas and paintings, Venetian canals and bridges. The lesser arts also hold their own: pastas, sauces, and olive oils pay homage to the fine art of cooking, celebrated nowadays even in gas station stops along limited access highways. Like innumerable foreigners before me, I have been captivated since my first visit in 1966 by the classic Italian devotion to beauty, by the historic areas and their remarkable cultivation of beauty.

But that's just the historic areas. Leave those and ugly modernity quickly intrudes. In Bologna, for example, once you exit the Renaissance town center, you bump into Stalinist-style buildings, hideous storage tanks, and oppressive graffiti (an Italian word, by the way).

Stalinist-style buildings outside Bologna's historic center. |

A holding tank and possibly the ugliest site in Bologna. |

Graffiti is an Italian word, as these store-fronts in Bologna remind one. |

If architecture is the most ubiquitous expression of decay, painting, sculpture, and music suffer from the same woes, a point extravagantly proven every two years by the famed Venice Biennale. Opened in 1895 and held during odd years for an interminable six and a half months, its contents contrast spectacularly with the transcendent beauty of its host city, Venice. Among the unique blend of canals, gondolas, medieval palaces, and baroque churches, neighbor to the highest of the arts, sit a former factory and warehouse full of the sad and miserable excrescences known as modern art.

Venice' transcendent beauty, as seen from a water taxi. |

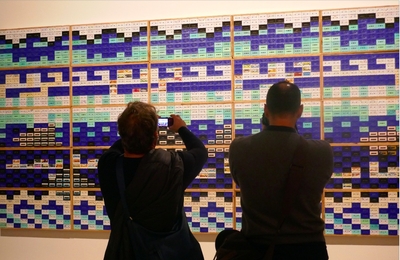

I traipsed from hall to hall of the 57th biennale, expecting to find didactic, pedantic, and politically radical exhibits. To my relief, overtly left-wing politics were nearly absent; instead, I found the dreary vacuity of mostly pointless shapes, pictures, and words. Most artifacts seemed childlike, relying on boisterously primary colors, simple shapes, and simplistic messages. Skill, beauty, and meaning were all conspicuous by their absence: A hammock loaded with random papers. Hanging sneakers with plants growing from them. A mural made up of audio cassettes.

The Biennale's management is particularly proud of its primary colors display. |

Studied interest in a hammock stuffed with miscellaneous papers. |

Fascination with hanging sneakers stuffed with plants. |

Not quite Leonardo da Vinci; a mural made up of audio cassettes. |

Only a perverse exhibit of mock corpses that featured rotting organic matter contrasted with this blandness; the catalogue has the nerve to call these nauseating figures an "aesthetic and ecstatic transfiguration" creating "a new magical world."

Dangling corpses made out of rotting organic matter are "magical" or "sexy"? |

It came as no surprise to learn that the New York Times' review of the Biennale's current iteration berated it for being too apolitical in the age of Brexit and Trump. Fine: But calling the decayed-corpse exhibit "sexy" appalled me for its overt implication of necrophilia.

I felt tempted to shout out to the horde of art worshippers, "The emperor has no clothes. This is a fraud. Leave this bleak place and instead visit Venice's exquisite streets, waterways, churches, and palaces." But exhibit-goers had each paid an entrance fee of €25 (US$30) and, judging by the many photographs being snapped and the learned discussions underway, the Biennale cheerfully satisfied their artistic tastes. So, I stayed mum.

Two concluding observations: Venice is arguably the world's most exotic and beautiful city; how ironic that it spawned among the most prominent purveyors of dreck masquerading as art. One hundred and seven years after Woolf's December 1910 turning-point, one wonders how much longer the farce of modern "art" will continue, when leading artists will repudiate politics and instead rediscover the ageless goal of creating beauty?

Mr. Pipes (DanielPipes.org, @DanielPipes) has enjoyed the arts in 88 countries. © 2017 by Daniel Pipes. All rights reserved.

Dec. 28, 2017 addenda: (1) Thomas Beecham: "All the arts in America are a gigantic racket run by unscrupulous men for unhealthy women."

(2) Wilfrid Scawen Blunt told of visiting the Grafton Gallery to look at Post-Impressionist pictures from Paris. He found the drawing

on the level of that of an untaught child of seven or eight years old, the sense of colour that of a tea-tray painter, the method that of a schoolboy who wipes his fingers on a slate after spitting on them. ... These are not works of art at all, unless throwing a handful of mud against a wall may be called one. They are the works of idleness and impotent stupidity, a pornographic show.

(3) Robert Frost: "I'd as soon write free verse as play tennis with the net down."

(4) My father, Richard Pipes, explained the vacuity of modern art as follows in his 2003 memoir, Vixi, p. 119:

A person educated in the history of art can date a Western painting within a few decades. With Oriental paintings this is almost impossible to do because the artists strive not at originality – that is, surpassing their teachers – but at perfection, at the best possible representation of an object, which may have been attained a thousand years earlier. The same holds true of our music. This constant striving for originality is a source of Western creativeness, but in the end it has led to self-destruction. When twentieth-century painters and composers were no longer able to improve on their forerunners, they capitulated. A painting that is a pure white canvass or a composition consisting of several minutes of silence mark a rejection of art, since, by definition, a painting is a design and a musical composition, sound.

Dec. 29, 2017 update: See the exchange between Brian Yoder and myself here. The topic is Fred Ross' philosophy of the Art Renewal Center.

May 6, 2019 update: What will the Biennale come up with next? A floating coffin. ArtNews reports:

On April 18, 2015, a fishing boat that left Tripoli, Libya, carrying hundreds of migrants crashed into a cargo ship coming to its rescue and sank in the Mediterranean Sea. A United Nations investigation concluded that more than 800 people died on the ship, which was designed to be operated by a crew of about 15. Only 27 people survived. ...

More than a year after the tragedy, the Italian government brought the shipwreck to the surface and transported it to a NATO base in Augusta, Sicily, where it has been for the past three years. Now it is coming north, to appear in the central exhibition in the Venice Biennale, "May You Live in Interesting Times."

The shipwreck being moved to its Biennale installation in Venice. |

July 7, 2019 update:

Here's a mischievous but deadly serious question:

Which is the more awful "art", #Stalin's or the Venice Biennale's (@la_Biennale)?

- Both are political kitsch

— Daniel Pipes دانيال بايبس (@DanielPipes) July 8, 2019

- But #SocialRealism is for the simple minded & #AvantGardism for the sophisticated

- The one lies, the other perverts pic.twitter.com/mgd1DX1FPF

#JamesJoyce: "I've put in so many enigmas & puzzles [in "Ulysses"] that it will keep the professors busy for centuries arguing over what I meant & that's the only way of insuring one's immortality."

Me: I've finally found the key to "serious" modern art. It's for the professors. pic.twitter.com/zmGm2esQp0

— Daniel Pipes دانيال بايبس (@DanielPipes) December 25, 2020

Apr. 27, 2021 update: According to a semi-serious conspiracy theory reported by Zach Mortice at Bloomberg,

A vast, technologically advanced "Tartarian" empire, emanating from north-central Asia or thereabouts, either influenced or built vast cities and infrastructure all over the world. (Tartaria, or Tartary, though never a coherent empire, was indeed a general term for north-central Asia.) Either via a sudden cataclysm or a steady antagonistic decline — and perhaps as recently as 100 years ago — Tartaria fell. Its great buildings were buried, and its history was erased. After this "great reset," the few surviving examples of Tartarian architecture were falsely recast as the work of contemporary builders who could never have executed buildings of such grace and beauty, and subjected them to clumsy alterations.

Comment: Well, that's one way to account for the decline in architectural standards.

For more discussion of the Tartaria thesis, see here, here, and here. (The later versions are more compelling than the earlier ones.)

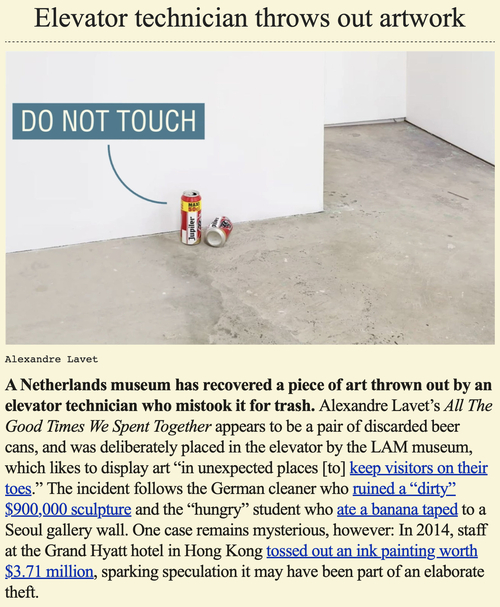

Sep. 25, 2021 update: Modern "art" is so absurd that the audience cannot tell what's art and what's a janitor making a mistake:

Philippe Pareno's exhibit at the French gallery Luma Arles was inundated with water on the floor, the Economist reports, when "the triangular pool in one corner of the gallery on the ground floor began to overflow. Visitors were more entertained than upset as the water mercilessly penetrated across the parquet floor. The circular blue carpet in the center of the room darkened, and even when it got dark, spectators suspected it was part of the show." In fact, however, "Penetration from the overflowing pool in the corner of the gallery turned out to be the result of craftsmen accidentally leaving taps [on]."

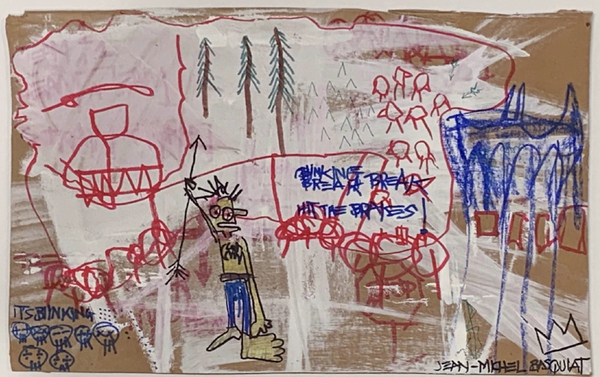

Aug. 21, 2023 update: Bad enough that an art auctioneer, Michael Barzman, could successfully forge 20-30 paintings by Jean-Michel Basquiat; worse that he and an accomplice "dashed off the forgeries quickly, spending between five and 30 minutes on each cardboard painting."

Comment: Take a look at one of their fakes, below, and see if you and an accomplice couldn't produce something similar in a matter of minutes.

A fake Jean-Michel Basquiat the FBI seized from the Orlando Museum of Art. Photo courtesy of the U.S. Attorney's Office, Central District of California. |

Oct. 8, 2024 update: From today's issue of Semafor.

For more details, with delicious quotes, try the Times of London.

Nov. 17, 2024 update: My dispatch from Venice.

Visiting Italy reminds me that the term "modern art" verges on the oxymoronic. pic.twitter.com/11XRf9yOGb

— Daniel Pipes دانيال بايبس 🇺🇦 (@DanielPipes) November 17, 2024

Nov. 21, 2024 update: Another blast along the same lines:

That a banana purchased for 35¢ sold for $6.2 million confirms my view that "Modern art is an oxymoron and its patrons are morons."https://t.co/wLCS6U9pBX

— Daniel Pipes دانيال بايبس 🇺🇦 (@DanielPipes) November 21, 2024

The Upper East Side fruit stand where the magical banana was purchased, then went up in price about 18 million times. |

At the rate of 35¢ per banana or four for a dollar, by the way, $6.2 million would buy 24.8 million bananas. Nov. 28, 2024 update: Further compounding the absurdity of these transactions, the buyer of the $6.2 million banana has now offered to buy 100,000 bananas from Mr. Alam.

The 3J Art Gallery in Brussels on Oct. 3, 2025.

Apr. 25, 2025 update: Another Dutch museum (see the Oct. 8, 2024 update for the first), but this time ending in mock tragedy. Forty-six works of art, including an Andy Warhol creation, disappeared from the town hall of Maashorst, "accidentally taken away with the rubbish" in the words of its mayor.

Oct. 3, 2025 update: Walking by the 3J Art Gallery in Brussels today, I noted seven hard hats on a table and wondered to myself if they are what workers left behind or an art installation.

Oct. 7, 2025 update: In a highly unusual analysis, the New York Times asks, "Did a Single Generation Ruin Modern Music for Everyone Else?"