Those Weak-kneed Allies

"Don't put Ireland's name on any piece of paper." With a touch of mock alarm, the Irish delegate to the United Nations Commission on Human Rights in early 1988 let it be known that his government could not be associated with a resolution condemning human rights abuses in Iran. He would vote for it, to be sure, but he feared Iranian retaliation if Ireland were seen as the resolution's sponsor. To understand this fine distinction means entering into the unusual world of the United Nations. To an outsider, it would seem that everything boils down to a yes or no vote; but this would be too easy. Diplomats have dozens of ways to shade their intent.

The Irish admitted their worries more openly than others, but except for the United States, every Western government shared their apprehensions. Actually, the Irish were among the brave, for many states refused to have anything at all to do with sponsoring the resolution. The Europeans felt so skittish because Iran's government is dangerous; introduce a resolution in Geneva, and who knows where hostages will be taken or acts of terror perpetrated. When the subject of Iran arose, the French delegate scurried from the room, smiling tightly as he claimed an "urgent" meeting. The Japanese ambassador muttered, "I want to escape." The West German and Italian delegates slunk off without showing even this much embarrassment. In the end, then, no government volunteered to put its name on the Iran resolution. Jokingly, it became known as the "IBM resolution," the computer being its only means of identification.

Although the United States suffers from more acts of hostage-taking and terror, Washington was perfectly happy to place the American name on the resolution. But the Europeans saw us as a kind of contamination which might cause others not to support the resolution, and requested that we not put our name on it. So, I had to stay quiet, witness to these dismal acts of European caution and unable to do a thing.

This and other examples of European cowardice at the Human Rights Commission suggest the feeble quality of American allies. On many contentious issues important to the United States - Cuba, Chile, war crimes - they either exert minimally on our behalf or obstruct American wishes. Most unimpressive of them all, perhaps, were the West Germans, stalwarts of avoiding confrontation and seeking consensus. Their showing prompted a Belgian delegate to smile and observe, "I wish my father and grandfather had faced that kind of German in two wars."

The allies vote in a pack. They prefer not to take individual stands on important issues. Delegates on occasion receive instructions known as "VIGC," or vote in good company. This means joining what the other European states do; revealingly, the United States is not considered good company, for it breaks rank too often. The Americans are too rowdy, overly concerned with injustice and morally compelled to speak for those who have no voice. Not good company, in other words.

The Western states are bureaucratic and bloodless at the Commission, their initiatives lack punch, and they shy away from confrontation. Their favorite instrument is the airy condemnation of abstract ills. They sponsor endless resolutions that abstractly condemn practices such as summary execution, religious intolerance, torture, and child abuse. This approach has the advantage that everyone can agree, names never need be specified, and nasty regimes are not provoked. In contrast, the Americans want to address the behavior of specific states - Cuba, Ethiopia, Iran - and accept the hostility this generates. Not surprisingly, when the U.S. government declared that a resolution on Cuba would be the centerpiece of its 1988 effort in Geneva, not a single European state signed up as a co-sponsor.

Actually, the Europeans do take interest in a few regimes, but these are invariably pro-Western states, preferably small ones. For example, the Swedish ambassador specified by name five evil states. In his mind, which are the five worst states? Guatemala, El Salvador, Chile, Israel, and South Africa. The only communist state noted by Europeans was Afghanistan (and a historical reference to Cambodia under Pol Pot).

Differences between Americans and Europeans go deeper. Even when censorship and torture are the topic, the Europeans' real interest seems to lie elsewhere - in the deliciously complex and near world of procedure. Political prisoners languishing in jail make their blood race less than the give and take of diplomatic niceties. Chairman's requests, issues of implementation, interventions from the floor, secretariat plans, regional consensus, voluntary funding, operative paragraphs, tours de table, motions for no action, and multiple ballots - these are the topics of real interest. Procedure provides a sense of purpose to governments reluctant to confront regimes with the evil of their behavior.

This contrast emerged most strikingly at a meeting of the Western group on the morning of Mar. 3, 1988. European representatives droned on for nearly an hour about items, motions, and instructions. Not an American said a word. At the end of this routine prattle, the chairman asked if there was other business. The leader of the U.S. delegation, Ambassador Armando Valladares, a victim of the Castro regime in Cuba, asked for the floor. Valladares spoke not of consultations nor of the deletion of a few words from a preambular paragraph, but of the need for active support for the American resolution on Cuba. He appealed for help in convincing the undecided states. His raw energy and clear delineation of the issues left the Europeans - not for the first time - bemused and slightly repulsed. "There go the Americans, injecting polemics into an otherwise civilized exchange" was the unstated but almost palpable response.

Symbolic of all this, the Western states often serve as intermediaries between the United States and the rest of the world. Thus, in response to the arrest of Desmond Tutu in late February 1988, the African states cobbled together a resolution which the Norwegian ambassador brought to U.S. attention. The American response was reasonable; give us a day to discuss this with Washington and we can probably accept it. To this, the Norwegian replied, "All right, but the Africans may not be pleased." Implicit in this statement was an equidistance between the two sides.

The Commission

The United Nations Commission on Human Rights has 43 members, or one quarter of the whole UN membership. Members are selected by the members of the five regional groupings. The Western European states, Turkey, New Zealand, Australia, Japan, Canada, and the United States (but not Israel) form what is known in UN parlance as the West European and Other Group (WEOG, pronounced WEE-og). Latinos, Africans, Asians, and the Soviet bloc form the other four groups. The WEOG forms a tight group whose members meet every morning at the West German mission, confer through the day, and socialize almost every evening. More than that: they live together. My hotel housed no one but members of the WEOG - Finns, Swedes, Norwegians, Danes, Irish, West Germans, and Britons.

Members of WEOG are shown in blue. |

The distorted world of the UN bestows more voting power on the African group, with its roughly fifty members, than on the West, which has only half that many votes. Further, the Africans vote more en bloc, and so enhance their power. But numbers are not everything, even in the UN. The Togolese speech goes into the air, but the American one is carefully noted down and copies of it sent to the capital for study. And the same goes for the voting, where quality counts nearly as much as numbers. Everyone knows that U.S. support makes a resolution count. This does give Washington some leverage.

Amazing efforts go into the formulation of resolutions, with long discussions on the tiniest questions of grammar and punctuation. Close your eyes and you can imagine yourself writing a peace treaty; but it's just a toothless statement of intent.

Voting comes as an anti-climax. It includes very few surprises, for almost everything is wired in advance. Poll-taking here works. The many resolutions that go through on consensus take about ten seconds to dispatch. Contested ones have to be voted on, of course, but even these are decided up or down within two minutes.

As a wag has observed, an organization with over one thousand persons does not need contact with the outside world. This applies triply well to an organization that does not earn its keep. The UN exists in a cocoon of its own, self-contained, often scornful of reality.

It is deeply ironic to recall that the United States, in its innocence, created this monstrous institution four decades ago. We may now disavow our achievement, but we cannot kill it. The UN has become a permanent fixture. But the key question remains: should we be in it or out? Staying in means legitimating the organization and making it more important; opting out means abandoning a significant platform to the enemy.

An answer probably lies in careful selectivity. The Commission on Human Rights contains issues that make up our agenda, and is therefore probably worth U.S. participation. The Soviets keep trying to derail the Commission's work from political rights to economic rights, but without much success, for the rights they are promoting have little resonance in the outside world. My favorite is the Mongolian resolution on the right to housing - a guaranteed yurt for every family? But other UN organizations work entirely to our disadvantage. Put differently, human rights serve Western interests at the UN, disarmament serves the Soviet Union, and development serves the Third World.

From the point of view of traditional statecraft, the United Nations Commission on Human Rights is a bizarre phenomenon, for it institutionalizes interference in the internal affairs of other states. It also calls on the state to use its offices not to forward its own interests but to represent the weak and despised. These two factors go far to explain the queasiness many diplomats feel about the undertaking; they also account for the log-rolling, horse-trading, and other cynical practices that prevail. Indeed, there is no shame in this; in replying to a request from Secretary of State George P. Shultz for a "yes" vote on Cuba, the foreign minister of a nominally pro-American state (Pakistan) explained that he could not do so because he often depends on Cuba's vote.

In UN debates, knowledge of the real world matters far less than mastery of the details of procedure, voting patterns, past resolutions, and the character of the delegates. Assigned the Iranian and Afghan briefs, I prepared for the commission by studying the current situations in Iran and Afghanistan. Then I learned how useless this was in so far as the UN was concerned. Indeed, reference to the outside world spurs controversy, and is discouraged; quoting UN documents is much safer, and therefore preferred. Accordingly, each text is a palimpsest building on prior UN resolutions and UN reports.

The Human Rights Commission has no instruments of power; its influence lies entirely on its actions becoming known and accepted by the public. (In this, it resembles a private organization more than a governmental one.) The Commission needs media coverage; nonetheless, delegates are so caught up in the minutia of UN activities, they actually resent the presence of the media. Thus, after television cameras and lights recorded the U.S.-Cuban clash, a British delegate turned to me and said, "We really don't care for this kind of media extravaganza, you know."

However insignificant to the United States, multi-lateral diplomacy has a prominent place in the diplomacy of many small states, for they see the UN providing their unique opportunity to exercise an influence, however meager, on world affairs. The UN offers a forum to opine and vote on the great issues of the day. Malaysians vent their views on the Arab-Israeli conflict, Swedes offer solutions to the South African impasse, and Zambians express their views on nuclear disarmament. Many small states devote disproportionate resources to the UN, including the dispatch of some of their most accomplished diplomats.

These talented individuals are in a bind, for they are essentially marking time in a loud but unimportant institution. To feel they are putting their efforts to good purpose, they must convince themselves into thinking that the UN in fact has real importance. This leads to a mutually supportive attitude that what happens at the UN really counts. The Soviets humor this illusion, leaving Americans posted there as the only ones to express skepticism about the whole undertaking. For the others, process becomes an end in itself. Or, as a cynical American delegate put it, "The game is the game." The UN resembles the model UN, where procedure is all, and so turns into a self-parody.

A Typical Day

Geneva is the city with by far the most diplomats per capita, and one feels it. The guests at my hotel were, every last one of them, diplomats. This gave the place its own distinctive rhythms. The breakfast room filled up at 7:00 a.m. and everyone had left by 8:15. No one returns until the evening. Virtually everyone disappears for the weekend. All the guests pay promptly. No one has children and noisy parties are unheard of.

I fitted the mold exactly. Out of the hotel each morning by 7:30 a.m., I joined two other American delegates to walk to the U.S. mission. We used the half hour to ruminate over the previous day's events and conspire for the day ahead. On arrival at the mission, we read "the traffic" - reports and instructions from the State Department - for a few minutes, then had a staff meeting for the fifteen or so members of the (huge) American delegation.

Almost every day, we arrived late for the 9 a.m. WEOG meeting at the West German mission. Despite its unofficial nature, it is a formal meeting, complete with the ritualistic "Thank you, Mr. Chairman," at the beginning of each statement. In fact, the WEOG constitutes a proto-UN made up of 22 democratic states which see eye-to-eye on first principles but disagree on issues. I suspect the future of international organizations lies in this sort of grouping.

Not surprisingly, every one at the WEOG speaks in English, except the French. Apparently, this has to do with our meeting in Geneva, a French-speaking city, for even they use English in New York.

Le Palais des Nations, seat of the United Nations Commission on Human Rights. |

One of the oddest features of the Commission is the presence at desks of private organizations, dubbed non-governmental organizations (or NGOs) in UN parlance. Sovereign states, usually so jealous of their prerogatives, allow representatives of these groups - which range from such groups of international stature as Amnesty International to one-man fronts - well over half the time on the floor.

Speakers sit at their seats, talk in normal tones, and there is no amplification. One hears what is going on only by attaching an earphone; it is necessary to put on an earphone even for one's own language. The scene resembles the interior of an airliner cabin, where one hears what is going on by putting on an earphone. This arrangement enhances the sense that speechifying is secondary, that nothing should get in the way of the chat and negotiating going on in the hallways.

It is just as well that speeches are so underplayed, for they are mind-numbingly tedious. Even the Western declarations tend to be unbearably technical and abstract.

UN speeches are simultaneously translated into English, French, Spanish, Arabic, Chinese, and Russian, so I tried to amuse myself during the torpid patches by tuning in on other languages. It appeared to be an opportunity to polish up some foreign languages, but I quickly learned otherwise; if the speech is too unbearably boring to listen to in English, it certainly does not improve in a foreign language. Still, flipping the dial did offer some amusement.

After three hours of this, the session breaks for lunch at 1 p.m. Most Americans go back to their Mission to eat subsidized food (U.S. government allowances barely cover daily costs in Switzerland) and report to the State Department about the morning's activities. After lunch, the telephone calls to Washington (which is six hours behind Geneva time) begin. This is amazingly easy to do from the Mission: punch just two digits and you are instantly within the State Department telephone system. The quality of this connection is not terribly good, but the immediacy creates a psychological tie to the Department.

Delegates return to the belly of the beast at 3 p.m. for three more hours of oratory. But windy speakers proliferated so much that time got short toward the end of the annual meeting, so sessions would drone on into the evening - to 9 p.m. and once even to midnight.

Most evenings, receptions begin right after work ends. These offer a curious sort of social life. They have a certain glamour - engraved invitations, fine houses, elegant waiters, delicate canapés - but they too are tedious. The parties, in fact, are no more than an extension of the working day. The guests are invariably Commission delegates, and usually Western ones at that - the same crew we've been with all day. To make matters worse, everyone is hungry by 7 p.m., and however exquisite, canapés do not make a good dinner. (This is perhaps the most important lesson I learned at the UN.)

The most dedicated American delegates returned to the Mission after the reception to tend to cables again. Not me: returning to the hotel room, I had just enough time to unwind for a few minutes in front of the television set (there is no television in the free world so boring as that of the German-language Swiss station) before nodding off.

The Cuba Offensive

One of the worst features of the UN is the way it forces governments to go on the record by voting on issues that do not concern them. Thus, in the Commission on Human Rights, Rwanda votes on developments in Iran, Peru decides whether or not to favor armed struggle in South Africa, and São Tome & Principe passes judgment on human rights abuses in Cuba. And here hangs a tale - the American effort to win an abstention from São Tome & Principe.

The appointment of Armando Valladares as U.S. representative to the Commission in 1988 signaled a renewed American effort to get Cuba on the agenda. This made sense, for the Havana government is an egregious violator of human rights. More than that, making Cuba a focus of attention also served other goals: it put the Commission on notice that the incessant attention to El Salvador, Guatemala, and Grenada would have a cost; it launched a propaganda offensive against the Soviet bloc (which, with the one exception of Afghanistan, is never subjected to human rights inquiries); it put Fidel Castro on the defensive; and it had the potential to improve the conditions of political prisoners in Cuba.

To win a maximum number of votes, the resolution was phrased in the mildest possible way, drawing on Red Cross and other findings, keeping an open mind about their accuracy, and calling only for consideration of Cuba at next year's session. But if the resolution itself was mild, the U.S. government effort to get it accepted was by most accounts the greatest undertaking at the UN since the China question of the early 1970s. Some even called it the greatest ever. President Reagan sent letters or telephoned one-third of all the Commission members. Vice President Bush and Secretary of State Schultz were also heavily involved. Embassies everywhere engaged in lobbying; friends were called upon; chips were called in.

A stream of prominent visitors joined our efforts in the final days before the vote. Dante Fascell and William Broomfield, chairman and ranking minority member of the House Committee on Foreign Affairs, turned up in Geneva with six staffers for one full day's effort; they began lobbying at the WEOG at 9 a.m. and finished their work over dinner at 11 p.m., then went home. (This was no junket.) As Fascell and Broomfield have something to say about both foreign aid and the UN budget, they received a respectful hearing. Vernon Walters spent a day with us, jaw-boning the recalcitrants in his many languages. Maureen Reagan turned up and lent her presence for three days. Of course, the Cubans were making their best efforts against the resolution.

The daily tally showed the voting to be very close. This is where São Tome & Principe came in. Its vote was looking pro-Cuba but the grapevine said it could be changed to an abstention, so we bore down to effect a switch. In the course of our efforts, the American delegates learned a few facts about São Tome, such as the size of the country (963 km2, or the equivalent of New York City), its population (88,000), its GDP ($30 million, the turnover of a good-size American grocery store), and the per capita income ($310 a year). Further, we learned that foreign aid makes up 41 percent of the GDP. Even more interesting was the fact that the native army consisted of 150 men, while its Angolan troops numbered 1,500 and its Soviet and Cuban troops came to 2,000.

This last fact bore directly on our efforts. It may have been coincidence, but just a day before the Cuba resolution was scheduled to come to a vote, 43 men on canoes attempted a coup d'état in São Tome and were routed by none other than the Cuban soldiers. This also may have had something to do with the failure of our extensive efforts to convince the São Tome authorities to abstain.

In the end, this did not matter, for there was no vote. Seeing they were down by two or three votes, the Cubans did what they had to do to avoid the humiliation of being put in the docket by the United States. They went to several Latin American states and put the arm on them to offer an alternate plan. (An incident with a senior Peruvian delegate clarified the role of intimidation for the Cubans. In the face of an almost complete lack of cooperation, an American chided him, "You're doing this because you are afraid of the Cubans." In response, the Peruvian repeated in an dazed way, No tenemos mieda, "I'm not afraid," a dozen times. Repetition seemed to serve as an incantation to ward off the Cubans.)

Although Castro had recently declared on US television that he would never accept a UN committee of inquiry, he did just that. In fact, he invited a committee of six to visit Cuba. His offer was loaded, of course, for it only allowed visits to prisons and discussions with the "proper authorities." Even worse, the whole undertaking was to be on Havana's tab.

Two days of intensive discussions followed. Perhaps the most interesting aspect of these negotiations was the West Europeans' reaction, which was one of great excitement and irritation. They pointed out that acceptance of the Cuban offer would set a bad precedent, for then any state feeling the heat would be able to divert it by making such a limited offer. As usual, they concentrated on procedure more than on substance. UN precedents took up far more of their attention than the fate of the prisoners in Cuba.

The U.S. delegation adopted an astute position, telling the Latin states that it was interested not in humbling Cuba, but in advancing human rights. This meant it was willing to drop the U.S. resolution if it would be replaced by something at least as good. The terms of Castro's offer had to be changed to bring them into conformity with established United Nations regulations. First, the UN pays for the visiting committee; second, the committee draws on all persons and materials it chooses (outside as well as inside Cuba); third, it enjoys complete freedom of movement in Cuba. The Cubans tried every trick to escape this twist in their offer, but they accepted these conditions in the end. Too clever by half, they gave the United States far more than it had originally sought.

The Remarkable Americans

To me, the real surprise of my service was not the UN, which met all my (low) expectations, but the American delegation, and especially the career diplomats. Contrary to my own experience in the State Department, where I found Foreign Service Officers (FSOs) often sluggish, narrowly career-minded, and not nearly attentive enough to the national interest, the group working on the Human Rights Commission was superb. They showed toughness in defense of U.S. principles and a clear sense of strategy in pursuit of goals. The FSOs were multi-lingual and knowledgeable in the ways of international institutions.

Most remarkable of all, not one suffered from clientitis, the dread disease that causes diplomats to represent foreign interests to the United States rather than the reverse. Not one of my colleagues apologized for the UN, nor did they offer to compromise U.S. goals in pursuit of harmony. As someone who usually despairs of the FSO influence on the formulation of U.S. policy, my experience in Geneva came as a surprise and delight. FSOs, it turns out, are not always trying to give away the store.

Dennis Goodman, a deputy assistant secretary of state and the senior FSO on the Geneva team, has been working on UN affairs through the Reagan era but still - touchingly - retained a sense of wonder at the weakness of friends and perfidy of opponents. More than anyone else, he took responsibility for making the Commission on Human Rights serve U.S. goals. In addition to plotting the Cuba effort, he made sure that the other major issues - Iran, Afghanistan, Israel, South Africa, Chile - were dealt with without sacrifice to American principles, even if that meant going down to defeat.

W. Lewis Amselem and Gordon Stirling managed in the floor fight on Cuba. Amselem translated for Valladares (who speaks almost no English), worked the hall, and sent out the many telegrams galvanizing the State Department and the embassies to action. He was instrumental, for example, in getting President Reagan to call the president of Venezuela in search of his country's vote. Amselem must be about the most outspoken FSO in existence. He declared on the Commission floor that "Walt Disney must have been Soviet, Cuban, or Nicaraguan, because only his fertile imagination could have conjured up the fantasies put forward by those states." He then called the Soviet Union "an economic, technical, and human rights mess" and Cuba an "economic and social disaster."

Stirling looked at the voting on the Cuba resolution like the football player he once was, rejoicing when the U.S. gained a vote, despairing when a decision went for the other side. He devoted his intense energy almost single-mindedly to winning the Cuba resolution. As keeper of the vote tally, he berated the staff to keep doing more to track down possible votes.

If Stirling was the all-American on the team, Albert Gabriel Nahas was the cosmopolitan. Dapper, fluent in six languages, and uncannily capable of thinking in non-American ways, Nahas tirelessly worked the floor. He would chat quietly and at length with delegates, carefully delineate for them the importance Washington attached to the Cuba vote, and press them to join the U.S. effort.

Thomas A. Johnson, the legal adviser, provided savvy advice on tactics and procedures. A Marine Corps reserve officer and a veteran of many Human Rights Commission meetings, Johnson stayed mostly in the background of the Cuba fight. Instead, he spent most of his time putting out the myriad fires that a Commission meeting spawns - issues like misguided changes in the funding of the Commission or Soviet efforts to distort the resolution on torture.

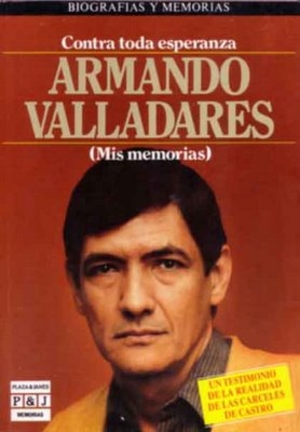

Cover of "Contra toda esperanza: Mis memorias." |

In other words, just five years after his release from a Cuban prison, Valladares represented the United States at one of the most visible of international fora. To make this remarkable tale even more unusual, Valladares does not know the English language well enough to function in it. He therefore delivered all his public statements (speeches, press conferences, interviews) in Spanish. Lewis Amselem provided translations at these events as well as in lobbying efforts, at staff meetings, and even in the lunch room.

At first, I had doubts about the wisdom of appointing Valladares head of the delegation. His not knowing English or the United States, his preoccupation with Cuba, and his ignorance of both the State Department and the UN seemed to me crushing disabilities. Further, it was easy to sense that his presence at the head of the U.S. delegation annoyed traditional diplomats, creating one more difficulty for the American initiative.

But I changed my mind on hearing the man talk. In part, I realized that the Commission is nothing if it is not a forum for the articulation of passionate resolve, and Valladares does that with great eloquence. In part too, I recognized that our strength lies in not playing by the traditional rules, so there is no need for a bureaucrat head the American delegation.

Finally, it was Valladares having to speak in Spanish that touched me. What a remarkable country the United States is that allegiance to its principles can outweigh the natural affinities of language and culture. And what a remarkable country that someone so visibly different and so newly a citizen can represent it. On hearing about Valladares' background, a Romanian with ten years' residence in Switzerland observed that his grandchildren could not even be sure of being Swiss citizens, much less hope to represent the country abroad.

Apr. 26, 1988 update: I refuted an ugly column by Alexander Cockburn, "Human Rights Ruling on Cuba Twisted Into Victory for U.S.," today at "Castro's Cuba: Fact or Fiction?"

Nov. 30, 2013 update: Twenty-five years after my stint at the UNCHR, Israel has become a member of WEOG.

Dec. 8, 2013 update: I served at the UNCHR in March 1988 because Richard S. Williamson, who became assistant secretary of state for International Organization Affairs a month earlier, appointed me to the position. I note with sadness that he died today and offer my condolences to his family. He was precisely 4 months older than me.