In the span of a decade, the Ayatollah Khomeini has twice challenged Western civilization's deepest norms. By permitting a seizure of the American embassy, in November 1979, he violated the most hallowed laws of Western diplomacy. In February 1989, he struck again, by calling for the murder of British novelist Salman Rushdie, and of his publishers.

So far as an outsider can tell, Khomeini issued his recent edict to resist what he sees as a threatening, secular West. The chief irony of the affair, therefore, was that Khomeini succeeded in demonstrating how few in the West are prepared to stand up for its values - and least of all his chief intended victim, Salman Rushdie.

I. The Author

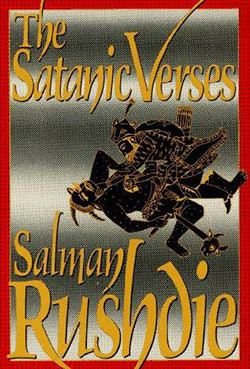

Salman Rushdie was born in 1947 in Bombay, India. He attended school at Rugby, followed by King's College at Cambridge University, from which he graduated in 1968. After spending two years in Pakistan, he returned to Britain, where he has lived ever since, becoming a British subject by marriage. For several years, Rushdie served as an editor in a public relations firm; then, in 1976, he published his first novel, Grimus, a work of science fiction. A second book, Midnight's Children, came out in 1979, won the Booker prize in 1981, and sold an impressive half-million copies. A 1981 novel, Shame, which dealt with Pakistan, also won high critical acclaim.

The Iranian press has called Rushdie "a self-confessed apostate," but he is better described as a lapsed Muslim, and he makes no bones about it: "I do not believe in supernatural entities," he has said, "whether Christian, Jewish, Muslim, or Hindu." Though Rushdie is hardly alone in his views, what he stands for perturbs many Muslims. They take particular offense because he has renounced his ancestral country, language, and the Muslim way of life, adopting instead England, English, and secularism.

But though Rushdie has adopted England as his home, he has hardly taken it to his bosom. The immigration officials who arrest one of his characters behave like the goons of a police state, "thumping and gouging various parts of his anatomy" in such a way that the bruises will not show. As Cheryl Benard of the Baltzman Institute in Vienna concludes, it is not Muslims who come off worst in Rushdie's vision. "It is Britons more than Moslems who might have cause to find the book 'blasphemous.' If Islam is portrayed as somewhat rigid and medieval, then the contemporary West, in his pages, is a nightmare out of 'Blade Runner.'" New York City he calls "that transatlantic New Rome with its Nazified architectural gigantism, which employed the oppressions of size to make its human occupants feel like worms." In the cruder terms of one of his characters, the West comprises "the motherfucking Americans" and "the sisterfucking British."

II. The Satanic Verses Incident

Nevertheless, it must be admitted, The Satanic Verses is an elusive and sophisticated tale, written by an accomplished novelist. Unfortunately, to assess the offensiveness of the book in Muslim eyes, the novel must be looked in a literal and anti-literary way, for this is the way it is understood by those who protest it. Specifically, one must take every statement in the book as representative of the author's own thinking, even though this is clearly not always the case.

Nevertheless, it must be admitted, The Satanic Verses is an elusive and sophisticated tale, written by an accomplished novelist. Unfortunately, to assess the offensiveness of the book in Muslim eyes, the novel must be looked in a literal and anti-literary way, for this is the way it is understood by those who protest it. Specifically, one must take every statement in the book as representative of the author's own thinking, even though this is clearly not always the case.

The Satanic Verses is not easy to summarize. It contains three stories which at first glance may appear unrelated. The first story (taking up chapters 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9) concerns two Indians (Gibreel Farishta and Saladin Chamcha) who fall out of a jumbo jet and miraculously survive. Their adventures in England, their fantasy worlds, and their eventual return to Bombay makes up the novel's central plot.

The second story (in chapters 2 and 6) is a dream about aspects of the story of Muhammad, the prophet of Islam. It relies partly on historical fact, partly on the novelist's imagination. The third story (in chapters 4 and 8) concerns a Muslim village in India whose whole population follows a holy woman into the Arabian Sea, expecting the waters will part for them to walk to Mecca. But the waters remain unparted, and virtually the whole village perishes. Juxtaposed as it is with a description of Khomeini's exile in Paris, Rushdie clearly intends this to be seen as an allegory for Iran and the Islamic revolution.

The dream about Muhammad is the source of the controversy. It makes up two chapters of the book, "Mahound" and "Return to Jahilia." (Mahound is an archaic European name for the Prophet Muhammad; Jahilia is Rushdie's name for Mecca.) From the Islamic point of view, the most offensive passages are those referred to in the book's title, those having to do with the Satanic verses, a little-known but genuine issue in the history of Islam.

Before looking at the Satanic Verses episode, however, an important point needs to be established about the Islamic faith, namely, that its irreducible core lies in acceptance of the Qur'an as the Word of God. At the very least, to be a Muslim means accepting on faith that God (or Allah, the same thing) sent His message to mankind via the angel Gabriel who passed it along to Muhammad; and that the Qur'an is inerrant. To doubt that the Qur'an is the exact message of God is to deny the validity of Muhammad's message and to imply that the entire Islamic faith is fraudulent at base. Therefore, such doubt is usually seen as an act of apostasy.

The Satanic Verses episode concerns the fact that Muhammad was born and lived in Mecca, long a major center of the polytheistic Arabian religions. Indeed, the town's prosperity depended heavily on its role as a religious center, and the leaders of Muhammad's own tribe, Quraysh, depended especially on those shrines.

The emphatic monotheism of Muhammad's message therefore posed a direct challenge to the existing order in general and to the leaders of Quraysh in particular. For this reason, Muhammad's initial teachings met with a poor response among the well-to-do in Mecca. The new faith did succeed in winning slaves, servants, non-tribal persons, and other riff-raff, but it made little progress among the burghers. Winning these over became a major concern of Muhammad's. It is in this context that the Satanic verses episode took place, in about 614 C.E., or one year after Muhammad began his career of public preaching.

At-Tabari (d. 923), a historian and commentator on the Qur'an who provides much of our historical knowledge about Muhammad's life, transmits the account as follows: "Members of Quraysh suggested to Muhammad that he adopt a flexible attitude toward their idols, and they in return would adopt a more friendly attitude toward his preaching. 'If you make some mention of our goddesses, we would sit beside you [i.e., become Muslims]'." Soon after this offer, Muhammad recited the following verse of the Qur'an, which made reference to three of the most prominent Meccan goddesses:

Have you thought upon Lat and Uzza,

And Manat, the third, the other?

At this point, according to the account in Tabari, Satan distorted the next words so that Muhammad accepted these three goddesses and confirmed the validity of their intercession between man and God:

These are the exalted birds,

And their intercession is desired indeed.

Naturally, Quraysh was delighted by Muhammad's acceptance of the three goddesses. It meant that Islam was neither as monotheistic nor as radical as it had first appeared. The traditional religions would live on, at least in an attenuated form; the shrines of Mecca would retain their economic value.

But then the angel Gabriel (the normal source of the Qur'an) came to Muhammad and revealed to him that the devil had deceived him into uttering the last two lines. To be precise, in Tabari's account, Gabriel revealed that "Satan caused to come upon his tongue" the verse about "the exalted birds." Gabriel abrogated these lines and replaced them with verses denouncing the cult of the three goddesses. The complete Qur'anic text on this issue reads as follows:

Have you thought upon Lat and Uzza,

And Manat, the third, the other?

Shall He have daughters and you sons?

That would be a fine division!

These are but [three] names you have dreamed of, you and your fathers.

Allah vests no authority in them

Even though guidance had come to them already from their Lord.

What had happened? Had Satan leaped on Muhammad's tongue? Or had the Prophet tried to ingratiate himself with the city leaders, then regretted the effort and recanted? Or, worse, had he tried to win their favor, been rebuffed, and changed the text accordingly?

Obviously, this incident is one of the most delicate in Muhammad's mission. Here is the way that W. Montgomery Watt, the leading modern biographer of Muhammad, steers a neutral course in his summary of the incident:

Muhammad must have had sufficient success for the heads of Quraysh to take him seriously. Pressure was brought to bear on him to make some acknowledgement of the worship at the neighbouring shrines. He was at first inclined to do so, both in view of the material advantages such a course offered and because it looked as if it would speedily result in a successful end of his mission. Eventually, however, through Divine guidance as he believed, he saw that this would be a fatal compromise, and he gave up the prospect of improving his outward circumstances in order to follow the truth as he saw it.

The phrase "as he believed" is Watt's way to avoid judging the issue. In other words, this is the territory of faith where the historian dares not tread. But the novelist does. Rushdie is a skeptic, and he treats the incident as one of deceit.

III. The Title

In Rushdie's novel, the prophet spoke the false verses not because Satan put them in his mouth, but because he saw an opportunity to advance his cause. Later, Mahound "returns to the city as quickly as he can, to expunge the foul verses that reek of brimstone and sulphur, to strike them from the record for ever and ever." To cover his deception, Mahound adopts the notion, put forward by one of his followers, that the devil made him do it.

But Rushdie's offense in this section goes beyond the charge that Muhammad weaved and bobbed as his interests changed; the real problem lies in the implication that the entire Qur'an derived not from God through Gabriel, but from Muhammad himself, who put the words in Gabriel's mouth.

Gibreel [Gabriel], hovering-watching from his highest camera angle, knows one small detail, just one tiny thing that's a bit of a problem here, namely that it was me both times, baba, me first and second also me. From my mouth, both the statement and the repudiation, verses and converses, universes and reverses, the whole thing, and we all know how my mouth got worked.

This last point ("and we all know how my mouth got worked") refers to Gibreel's being forced to say what he does by Mahound. If this is true, then the Qur'an is a human artifact and the Islamic faith is built on a deceit. There is nothing left.

But is that what Rushdie has implied? The whole sequence, after all, is part of a dream; and the dreamer, Gibreel Farishta, is a man whose name means "Gabriel Angel" and who suffers from "paranoid delusions" of being the Archangel Gibreel. Surely this places the author at considerable distance from the story he tells. Further, other Muslims have written on Muhammad and the Qur'an in ways objectively more offensive to Islam than Rushdie, and they have been attacked far less. For example, Ali Dashti, an Iranian whose works were freely available after the Iranian revolution, wrote an analysis of Muhammad's mission which included such statements as: "The Lord who made observance of ancient Arab lunar time-reckoning compulsory everywhere and for ever must have been either a local Arabian god or the Prophet Muhammad."

It is no wonder that Rushdie got negative reviews from Muslims, but why did Rushdie and his book so provoke the Muslims of England and South Africa, the Saudi authorities, mobs in Pakistan, and the Ayatollah Khomeini? Something about this book - other than its contents - had to arouse their ire.

The clue may lie in the fact that almost no one who protested the book had even read excerpts of it, much less the entire novel. That they could get so excited about a book that they had not read indicates that the source of their anger lay in what they did know. And what did they know? That an author named Salman Rushdie, living in Great Britain, wrote a book called The Satanic Verses. In short, they were aware of little beyond the title.

But the book's title has an impact when translated into Arabic that it does not have in English. Here is Rushdie's understanding on the matter:

Even the novel's title has been termed blasphemous; but the phrase is not mine. It comes from al-Tabari, one of the canonic Islamic sources. Tabari writes... [that] Muhammad then received verses which accepted the three favorite Meccan goddesses as intercessionary agents. Meccans were delighted. Later, the Archangel Gabriel told Muhammad that these had been "Satanic verses," falsely inspired by the Devil in disguise and they were removed from the Koran.

Rushdie's account is generally correct - but he makes one mistake. The exact term "Satanic verses" is not found in Tabari. Tabari says: "Satan threw [something] into his formulation, and these verses were revealed." Admittedly, this is close in spirit to "Satanic verses," but it is not the same. The term "Satanic verses" is an English one, devised by orientalists. When rendered into Arabic, the phrase becomes Al-Ayat ash-Shaytaniya, using a word for "verses" (ayat) which refers specifically to the verses of the Qur'an. Back-translated to English, therefore, the Arabic title would be "The Qur'an's Satanic Verses." And, with just a touch of imagination, that is easily rendered as "The Qur'anic Verses Were Written By Satan," or even, "The Qur'an Was Written By Satan" In other words, the book's title is not being taken (as it should be) to refer to a bit of Islamic arcana concerning phrases omitted from the Qur'an. It is being read to assert that the Qur'an itself was the work of the devil.

Herein lies the most probable direct cause of the furor. By hearing the title in this way, Muslims found it unimaginably offensive.

IV. The Initial Uproar

The uproar over The Satanic Verses began within days of the book's official publication in Britain, on September 26, 1988.

Indian Muslims learned about the book in mid-September from India Today, a bi-weekly magazine, which reviewed it, excerpted it, and interviewed the author. Presciently, the reviewer concluded that "The Satanic Verses is bound to trigger an avalanche of protests from the ramparts." And, indeed, Syed Shahbuddin, a member of the Indian parliament, not liking what he read in India Today, began a campaign to have the novel banned. He met with quick success, as the Finance Ministry prohibited the book on October fifth.

Meanwhile, Muslims in Britain heard from India about the book and began to agitate against its distribution. At first they tried having it banned, without success; then they tried protest and international pressure. The initial burning of The Satanic Verses took place in Bolton (near Manchester) on December 2, in a ceremony that attracted a crowd of 7,000 Muslims but scant press attention. Another effort was made on January 14, in the heavily Muslim town of Bradford, the so-called capital of Islam in the United Kingdom. The Bradford effort succeeded, as television news showed the auto-da-fé-the novel attached to a stake and set on fire-in loving, if horrified, detail.

Burning "The Satanic Verses" in Bradford, England. |

In reply, Rushdie published a statement that called the Prophet Muhammad "one of the great geniuses of world history," but noted that Islamic doctrine holds Muhammad to be human, and in no way perfect. He held that the novel is not "an antireligious novel. It is, however, an attempt to write about migration, its stresses and transformations."

British Muslims also alerted the London embassies of Muslim states about the book and its contents. But weeks passed and the states barely responded. The only disturbances were in South Africa, where local Muslims demonstrated against Rushdie's attendance at an anti-apartheid conference, forcing him to cancel.

All of this proved merely a warm-up for the round of violence that began in Islamabad, Pakistan, on February 12 and continued for a month. The events that day are clear, though their causes remain disputed. A crowd of some 10,000, took to the streets and marched to the American Cultural Center, where they shouted "American dogs" and "God is great" and set fires to the building. Five demonstrators died at the hands of the police as the crowd surged toward the building, and about a hundred were injured. A Pakistani guard at the American Center was shot by someone in the mob, making him the sixth casualty of the day. The next day, a rioter lost his life in Kashmir, India.

The odd thing about these riots was that British property was not attacked, although the novel had been out for months in the United Kingdom, and Rushdie was living in London. This may have had to do with the forthcoming U.S. publication of The Satanic Verses, scheduled for February 22. Or the violence may have been directed toward those in the opposition who wanted to exploit the opportunity to attack Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto - and the United States makes a better symbol of protest than Great Britain. Indeed, this is the way the prime minister interpreted the riots. Similarly, Rushdie accused the leaders of the demonstration of exploiting religious slogans for political ends.

V. Khomeini's Move

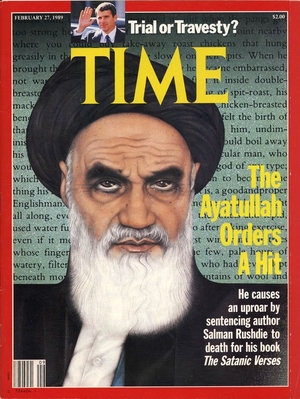

In any event, The Satanic Verses had caused, or excused, substantial disturbances among Muslims in several parts of the world by the middle of February. The disturbances and loss of life had attracted great attention, but there was no real political issue for the West to face. It took the Ayatollah Khomeini, a man who does not play by the usual rules, to mount that challenge.

The Feb. 27, 1989, issue of "Time" featured Khomeini's edict. |

However it happened, on February 14, Khomeini took the single most important step of the entire incident when, in an address to the "world's Muslim community," he pronounced an Islamic legal judgment (a fatwa, comparable to a Jewish responsa). Declaring The Satanic Verses in opposition to Islam, he pronounced a sentence of death on both Rushdie and his publishers.

The author of The Satanic Verses book, which is against Islam, the Prophet, and the Qur'an, and all those involved in its publication who were aware of its content, are sentenced to death. I ask all Muslims to execute them wherever they find them.

Khomeini called on Muslims to act quickly against Rushdie and promised martyrdom to whoever carried out the sentence. The president of Iran, Seyyed 'Ali Khamene'i, characterized Khomeini's statement as "an irrevocable dictum."

To make the task more attractive, the head of an Iranian charity organization, the 15th Khorbad [5th of June] Relief Agency, offered $1 million to a non-Iranian assassin and 200 million rials (almost $3 million at the inflated rate of exchange, but just $170,000 on the parallel market), to an Iranian. The next day, the religious leader of Rafsanjan (hometown of 'Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, speaker of the Iranian parliament) offered another 200 million rials, as did a mullah in Kerman.

Members of the Iranian parliament expressed their support for Khomeini and their "divine anger" at Rushdie. The Iranian ambassador to the Holy See announced that he would "kill Salman Rushdie with his own hands" if he could. The Islamic Revolution News Agency representative in Spain promised likewise (and found himself instantly expelled from the country).

More important, a number of groups sponsored by the Iranian government declared their determination to get Rushdie. Mohsen Reza'i, leader of the Islamic Revolution's Guard Corps announced the readiness of his forces "to carry out the imam's decree." Interior Minister 'Ali Akbar Mohtashemi called on Hizbullah to carry out the execution and the leaders of the Lebanese Hizbullah quickly promised to do "all that's possible to have the honor" of carrying out Khomeini's sentence. Other Lebanese groups, including Amal, the Islamic Unification Movement, the Jihad Organization for the Liberation of Palestine, and the Islamic Jihad for the Liberation of Palestine all promised likewise. In addition, Ahmad Jibril's Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine-General Command announced its intention to join the effort. The Revolutionary Justice Organization, went further than the others and vowed to attack the British police, if necessary, on the way to an assault on Rushdie. Something of a rivalry developed between these groups: Who would get to Rushdie first?

On the 17th, however, President Khamene'i announced that "the people might forgive him," if Rushdie repented. Accordingly, the next day, Rushdie did offer an apology, though a minimal one.

As author of The Satanic Verses, I recognize that Muslims in many parts of the world are genuinely distressed by the publication of my novel. I profoundly regret the distress that the publication had occasioned to sincere followers of Islam. Living as we do in a world of many faiths, this experience has served to remind us that we must all be conscious of the sensibilities of others.

The apology concerned the effects of his writings, not the writings themselves, and so did not mollify his critics.

Still, confusion in Iran followed, as a news agency report suggested that the apology, "though far too short of a repentance, is generally seen as sufficient enough to warrant his pardon by the masses in Iran and elsewhere in the world." Then the ayatollah weighed in, on February 19, with an absolute rejection of Rushdie's statement, and, indeed, of any act of contrition on his part. Khomeini denied foreign reports that repentance would lift the "execution order" against Rushdie.

Even if Salman Rushdie repents and becomes the most pious man of [our] time, it is incumbent on every Muslim to employ everything he has, his life and his wealth, to send him to hell. ... If a non-Muslim becomes aware of his whereabouts and has the ability to execute him quicker than Muslims, it is incumbent on Muslims to pay a reward or a fee in return for this action.

VI. Khomeini's Motives

Why did Ayatollah Khomeini turn The Satanic Verses into an international incident? Curiously, critics and supporters of the ayatollah have almost diametrically opposed explanations.

Critics are nearly unanimous in seeing his act in political terms. Former Iranian President Abolhassan Bani-Sadr saw the event as "a political affair and not a religious one," and the leader of the main Iranian opposition group, Mas'ud Rajavi of the Mujahidin-e Khalq agreed.

Some emphasized domestic political tensions in Iran. Amir Taheri saw The Satanic Verses as "an issue likely to stir the imagination of the poor and illiterate masses" in Iran. Harvey Morris saw it as a "revolutionary coup de théâtre" intended to replace the Iraq-Iran war as a focus of national unity. Others saw it mostly in terms of foreign policy. Youssef M. Ibrahim explained it as Khomeini's bid "to reassert his role as spokesman and protector of Islamic causes." William Waldegrave of the British Foreign Office blamed the incident on "radical elements in Iran, which do not want their country to have normal relations with the West and the Gulf states."

Supporters of the ayatollah, on the other hand, see his move very differently, primarily as a religious response. The top Iranian diplomat in Cyprus told a local audience that "the verdict issued by the Iranian leader is a purely religious one and based on the religious considerations." The chargé d'affaires in London stated unequivocally that Khomeini saw the punishment of Rushdie as "much more important than relations between two countries."

Which side is correct? Prima facie, there is strong evidence to accept the religious interpretation. First, there is the emotional side - a blasphemous parody of the Prophet, the evident courage of Muslims in England, the martyrdom of Muslims in Pakistan. In combination, these are likely to have exerted a powerful effect on the aged Iranian leader.

Second, the Muslims in India, Great Britain, and Pakistan who took to the streets before Khomeini spoke showed the depths of Muslim outrage. They had no connection to the struggles of Iranian political life.

Third, there are much more direct ways for Khomeini, the autocratic leader of Iran, to shut down relations with the West. He rules without rival; had he decided to stop the improving ties, he could simply have decreed so. A politician in his position of authority need not take so unusual a step as placing a bounty on a novelist's head.

Fourth, there is a persistent tendency not to take Khomeini's assertions at face value. This happened in 1978, as Iranians and others tried to foresee what kind of government he would impose in Iran. The evidence was all there, in the form of his writings over many years, but these tended to be ignored in favor of a more conventional interpretation of his goals. The insistence on a political explanation for the Rushdie fatwa risks falling into this same trap.

Finally, the attack on Rushdie is consistent with other actions by the ayatollah, two of which deserve mention. He took nearly the same step 47 years earlier, when he was yet an obscure mullah. In 1942 he wrote The Discovery of Secrets, a polemic directed against Ahmad Kasravi, a prominent writer whose anti-clerical views had gained a significant following in Iran. Khomeini pronounced Kasravi mahdurr ad-damm (forfeit blood), thus permitting a Muslim to execute him. His book was read by Mohammed Nawab-Safavi, who went on to found a terrorist group, the Fedayin-e Islam, and this group made Kasravi its first target. Inspired by the Khomeini tract, Sayyed Husayn Emami and three others attacked Kasravi with knives, murdering him. Though Khomeini's response to the execution is not on record, his close friend, Sheikh Sadeq Khalkhali called day on which it took place "the most beautiful day in my life."

Much more recently, Khomeini inflicted severe punishments on the producers of a Tehran Radio program called "Model for the Muslim Woman" for airing on January 28, 1989 what he called "an un-Islamic interview." A woman on the program had explained that she did not consider the daughter of the Prophet Muhammad, Fatima, to be a suitable model for herself; she preferred a more up-to-date exemplar - the heroine of a Japanese soap opera. Outraged, the ayatollah sent a letter to the director of Iranian broadcasting, telling him that if the insult was deliberate, the offending parties will "undoubtedly" be condemned to death. Three days later, the court sentenced one of the producers to five years in jail, two others to four years each and 50 lashes. And the court made clear that this relative leniency was due to an "absence of malicious intent" on their part; otherwise, all of them would have been sentenced to death.

Those (such as George Black) who argue that Khomeini "has used Rushdie as a target of convenience," are wrong. The answer is very clear (in the words of The New Republic): "The Ayatollah does not want to use Rushdie; he wants to kill him. We must respect the man's sincerity."

VII. Defending Islam

Nevertheless, a question remains about the ayatollah's motivation: why did he make The Satanic Verses a centerpiece of Iran's post-war diplomacy? Granted the offensiveness of the (literally interpreted) text, the offensiveness of the (misunderstood) title, and Khomeini's religious extremism, it is still not clear why this book should be made the Iranian government's top priority. The answer lies in the strange vision of history held by Khomeini and other fundamentalist Muslims.

Their view is based on a syllogism: Muslims were once strong, but are now weak. When Muslims were strong, they lived fully by the precepts of their faith, but now they do not. Therefore, Muslims are weak because they do not live up to the requirements of Islam. Were they to do so, they would regain the strength of centuries past. Khomeini's first goal, then, is to get Muslims to live fully by the law of Islam, the Shari'a. The just society, one where Muslims live in strict adherence to the Qur'an and the laws of Islam, is also the one which allows Muslims to achieve their natural strength.

But there is one great obstacle to achieving this: the seductive culture of the West, which has been drawing Muslims away from the exact adherence to their faith for two centuries. Therefore, Muslims must engage in a battle against Western civilization. And a battle this is, for the West is not a passive purveyor of culture, but actively thrusts it on vulnerable Muslims. The West does so because it benefits by weakening Muslims; this allows it to plunder Muslim lands and hire the believers as cheap labor. 'Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, speaker of the Iranian parliament, explained the deep historical roots of the effort:

From the day the Western colonialists harbored the intention of colonising the Islamic countries - or to be more precise, to demolish and create havoc in the Islamic world - they sensed that they must deal with something called Islam. They realized that as long as Islam is in force, their path will be a difficult one, or may be virtually closed off.Whoever is familiar with the history of colonialism and the Islamic world knows that whenever they wanted to get a foothold in a place, the first thing they did in order to clear their paths - whether overtly or covertly - was to undermine the people's genuine Islamic morals.

Of course, the imperialists could not entirely do away with Islam, so they did the next best thing, which was to emasculate the religion, reducing the faith to empty ceremonies devoid of real content. By 1978, ceremonial Islam (or "American-style Islam") prevailed at the state level everywhere in the world. But then, Rafsanjani continues, "with the advent of the Islamic Revolution, pure Islam entered the scene, and all they had done became undone." The Iranians threatened to lead all Muslims (and other oppressed peoples) against the hegemony of the great powers, the United States and the U.S.S.R. especially.

Seeing the danger Iran posed, the powers fought back. The White House and Kremlin feared that the explosive energy in Iran would destroy what the Iranians call global arrogance. "All the West's plots," explains President Khamene'i, "are aimed at stopping Islam and the revolution from becoming a world model." The Iranians have to engage in combat with all they have.

The war between Islam and "international blasphemy" has taken two main forms. First, the great powers put their agent, the Iraqi president, Saddam Hussein, up to a war which he obediently carried out. But military aggression failed against the hard rock of Islamic fervor. "After ten years," explains Mohtashemi, "the world gave up the hope of fighting Islam within Iran through military conflict."

Stumped, the foes of Islam had to find a second battlefront against Islam. The Western governments "summoned all their devilish experts and mercenaries to draw up anew a strategy against Islam." At the conclusion of all these efforts, global arrogance hit on a plan-warfare conducted (again) on the level of culture. The effort, according to a commentary on Radio Tehran, has two steps. First, "the aim is to weaken the Islamic faith among Muslims, thereby secularizing Muslims societies; this is then followed by an expansion of [Western] influence and the ultimate plundering of those societies' vital resources."

The Iranian authorities detailed a whole series of steps behind The Satanic Verses. Not for a minute did they believe the book had been written by a single author pursuing the whimsies of his own imagination. According to Rafsanjani, when Muslims read this book, "they will not see a mad Indian behind it; they will see Britain, Germany, France, and the United States." In his view, the Western intelligence services knew what they were doing when they picked Rushdie to be the ostensible author. They picked

a person who seemingly comes from India and who apparently is separate from the Western world and who has a misleading name [i.e., a Muslim name]. ... All these advance royalties were given to that person. One can see that they appointed guards for him in advance because they what they were doing. ... All this tells us of an organized and planned effort. It is not an ordinary work.... I believe there has not previously been such a well-planned act as this.

The effort required five years and $1.5 million. British intelligence even managed to have The Satanic Verses introduced as "the book of the year" in Britain. Had Muslims not protested, the book would have been made into a film.

But how, an outsider might ask, can this novel hurt Muslims? By making their faith and their traditions less honorable through distortion and ridicule. It hurts to be "ridiculed by world arrogance," and the pain turns Muslims against Islam. Fortunately, Muslims understood what was brewing, and they showed "with their rage" an intent to neutralize the plot. Their steadfastness stopped the cultural campaign in its tracks. The Iranian leadership portrayed the Rushdie incident as a major reassertion of Islam, and therefore a turning point in the fortunes of the faith. For example, a newspaper editorial explained how the Turkish government had been taking quiet but effective steps toward "ridding Turkey of Islam." But the shock of The Satanic Verses awakened the true Muslims of Turkey to the dangers in their midst.

Note that the Iranian leaders speak of "the West," or "global arrogance," for they do not believe that British intelligence acted alone in putting Rushdie up to the job; as ever, it worked hand-in-glove with its big brother, the United States. An Iranian government statement referred to the book as a "provocative American deed" and called Rushdie "an inferior CIA agent." As the interior minister, Mohtashemi, put it, "the book's author is in England, but the real supporter is the United States."

The irony of identifying Rushdie with the American government was not lost on saner voices. Rushdie, after all, is a Muslim of Indian origins who lives in England and holds a British passport. Further, he is widely known as a "man of the left," who almost always opposes the policies of the U.S. government. How, then, did Rushdie and the United States become intertwined in the minds of fundamentalist Muslims? Because Anti-Westernism has a way of turning into anti-Americanism. Britain may have been the imperial overlord, but now it is nearly defanged; the military threat is virtually gone. Too, American culture has a symbolic role. Whether Rushdie is living in London or New York City is a minor detail to fundamentalist Muslims; the point is that the United States presents the main threat, for it is the leader of the Western world, that lascivious place where it is acceptable, even encouraged, to attack the Prophet and the Qur'an.

VIII. Muslim Responses

One might have expected the world to have dismissed the twisted edict that came from Khomeini as madness, root and branch. But one would have been wrong.

On the official level, to be sure, the Iranians found little support. Only the Libyan government publicly stood by the ayatollah and his edict. The Kuwaiti government announced that it shared an "identical stance" with Tehran on the matter of The Satanic Verses, but it carefully avoided stating equal agreement on its author.

At the popular level, however, anti-Rushdie violence showed support for Khomeini. In the Indian subcontinent violent demonstrations continued for a month. The largest number of deaths in a single incident occurred on February 24th, when rioting in Rushdie's home town of Bombay turned into a three-hour battle between the police and fundamentalist Muslims. The rioters burned cars, buses, and even a small police station. In answer, the police killed twelve persons, detained 500, and arrested 800. On March 4, thousands of demonstrators ransacked part of the Karachi airport in protest against the Rushdie novel, smashing doors and looting the VIP lounge; this was their way of welcoming home from Iran the pro-Khomeini Shi'i leaders, Sajid 'Ali Naqvi. Naturally, the Iranians gloried in these demonstrations, calling them a "manifestation of Muslim power throughout the world" and "symptoms of this very majesty."

Confronted with such emotion, many leaders in Muslim countries sought to avoid the whole issue. They did not refer to it in public and they instructed their media to cover the controversy without comment. "I don't care to comment about the action of the Government of Iran myself," was King Hussein of Jordan's reply to a question on the subject. "Turkey is not a party to the arguments concerning the book," came the word from Ankara.

Although the authorities in all Muslim countries acknowledged the alleged blasphemy of The Satanic Verses, some did oppose Khomeini's edict. Not surprisingly, the Iraqi government felt no qualms about attacking it. President Saddam Hussein observed that "murder and incitement to murder is more harmful to Islam and Muslim than Salman Rushdie's tendentious and sinister book." The Egyptian foreign minister, 'Ismat 'Abd al-Majid, blamed Khomeini for creating the problem, and held that "Khomeini had no right to sentence Rushdie to death."

Several individual voices from the Arab countries also criticized Khomeini. In an act of singular bravery, Naguib Mahfouz, winner of the 1988 Nobel Prize in literature, called Khomeini's threat an act of "intellectual terrorism." Understandably, Muslims resident in the West felt freest to speak out. The chairman of the Imams and Mosque Council in Britain, Zaka Badawi, offered his own house as an asylum to Salman Rushdie.

From the vantage point of governments wishing to stay out of the picture, the easiest, least worrisome step was to ban the book and say no more. Indeed, few non-Western governments containing substantial Muslim populations resisted Saudi and Iranian pressure to ban The Satanic Verses, and many banned all books by Viking-Penguin. Even in Israel, the Ministry of Religious Affairs requested that the Keter publishing house drop its plans for a Hebrew translation.

The most notable exception to this pattern was Turkey, where the authorities hold an almost-religious devotion to the secularist principles laid down sixty years ago by Atatürk. Despite an overwhelmingly Muslim population, a substantial fundamentalist movement, and active Iranian pressure (the Iranian consul in Erzurum distributed copies of the Khomeini fatwa against Rushdie to religious leaders throughout eastern Anatolia), Ankara stuck firmly, if quietly and unhappily, to freedom of expression. It was a no-win situation. To take a stand against the book would damage the country's European credentials and reduce its chances of being accepted into the European Economic Community; not to take a stand would upset the many fundamentalist Muslims in Turkey.

Also, notwithstanding a long-standing Muslim rebellion in the Philippines, the government in Manila indicated it could not ban the book, for this would traverse constitutional guarantees of free speech.

IX. Non-Muslim Responses

Among non-Muslims, the Khomeini edict prompted responses in three stages. First, the week after February 14 was characterized by retreat and confusion. Publishers delayed or cancelled editions of the book, politicians temporized, even Rushdie apologized. Then, when it became clear that such concessions would win nothing in return from Khomeini, public opinion hardened and leaders adopted a more defiant stand, lasting from about February 20 to February 28. With the start of March a second round of retreats began, as writers, politicians, and religious figures turned against Rushdie. The controversy fell from sight in mid-March.

The governments of the West, who after all had both the responsibility and the means for protecting the rights of those threatened by Khomeini, responded in particularly timorous fashion. The British prime minister and the leader of the opposition, Neil Kinnock, kept silent about the ayatollah's threat for a full week. The newly-installed Secretary of State, James A. Baker 3d, could muster no more condemnation than to call the death threat "regrettable." The Canadian government temporarily banned imports of The Satanic Verses; worse, the government finessed the freedom-of-speech issue by relegating the decision to Revenue Canada, a tax agency. Bonn called the incident a "strain on German-Iranian relations." But it was the Japanese government that came out with the most spineless formulation of all: "encouraging murder," it intoned, "is not something to be praised."

Several governments - including the British, French and Soviet - sought a way out of the diplomatic impasse by noting that Khomeini's edict was issued not by the Iranian government but by the "spiritual leader" of the Islamic Revolution. Not only had ten years of experience shown this distinction to be utterly spurious, but the entire rank and file of the Iranian government fell all over themselves to align with Khomeini's action.

Moscow, which has a doctrinal antipathy in roughly equal measure for both freedom of speech and respect for religion, emerged looking rather well from the confrontation. Most impressive were the analyses offered in the Soviet media. In its Persian language broadcast, the Radio Peace and Progress said the call from Tehran for Rushdie's execution

is a source of great regret because it has eliminated the hopes... in the Soviet Union that the political crisis in relation to the said novel would die down.... Resorting to terror and threats in this way will have no other outcome for Iran but the exacerbation of international crises with dangerous consequences for Iran itself.

Another analysis on the station assessed blame even more bluntly: "Tehran's extremist reaction to The Satanic Verses has led to the current diplomatic war between Iran and the West." Similarly, Pravda referred to demonstrators supporting Khomeini as "Muslim fanatics."

Predictably, international organizations wanted nothing to do with the Rushdie issue, which polarized emotions and challenged the comfortable assumptions of a single order which underlie such institutions. Western efforts to condemn Khomeini at the United Nations Commission on Human Rights got nowhere, as the Muslim states made it clear they would oppose such efforts.

Finally, on February 20, the foreign ministers of the Common Market agreed on a strong statement about Rushdie and his publishers:

The Ministers of Foreign Affairs of the 12 member states of the European Community, meeting in Brussels, discussed the Iranian threats and incitements to murder against novelist Salman Rushdie and his publishers, now repeated despite the apology made by the author.The ministers view those threats with the gravest concern. They condemn this incitement to murder as an unacceptable violation of the most elementary principles and obligations that govern relations among sovereign states....

The ministers of the 12 decided to simultaneously recall their Heads of Mission in Tehran for consultations and to suspend exchanges of high-level official visits.

But though the British government withdrew all its personnel from Tehran and demanded that all the Iranian representatives leave London, it did not break diplomatic relations, insisting instead on what it called "reciprocity at zero." Observers knew of no precedent for the maintenance of diplomatic relations without any personnel; the British move was understood as a way of expressing strong displeasure and regret simultaneously - that is, normal relations could be built back up just as soon as the edict was retracted. But the Iranians, far from retracting, took the next step in the diplomatic dance; on February 28 the Majlis (parliament) passed a bill that stipulated a complete break on March 7 unless the British government declared "its opposition to the unprincipled stands against the world of Islam, the Islamic Republic of Iran, and the contents of the anti-Islamic book, The Satanic Verses."

Prodded by feelers from "pragmatists" in Tehran, British leaders did what they could to satisfy Tehran. On March 2, Foreign Secretary Sir Geoffrey Howe went on the BBC World Service to show foreign listeners that the government wished to distance itself from Rushdie.

We understand that the book itself has been found deeply offensive by people of the Muslim faith. It is a book that is offensive in many other ways as well. We can understand why it could be criticized. The British Government, the British people, do not have any affection for the book. The book is extremely critical, rude about us. It compares Britain with Hitler's Germany. We do not like that any more than the people of the Muslim faith like the attacks on their faith contained in the book. So we are not cosponsoring the book. What we are sponsoring is the right of people to speak freely, to publish freely.

Two days later, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher made similar remarks.

The Iranians acknowledged these gestures but demanded practical measures as well, such as the legal prosecution of the writer, confiscation of copies of The Satanic Verses, and injunction against further publication of the book. These steps the British authorities did not even consider undertaking; so, as threatened, Tehran broke relations on March 7. Its statement, a product of its conspiracy view, included some of the most unusual language and reasoning to be found anywhere in international diplomacy:

The statement noted that, "in the past two centuries Britain has been in the frontline of plots and treachery against Islam and Muslims," and it went on to provide details on perfidious Albion in Palestine, Iraq, Pakistan, and elsewhere. It alleged that London has suffered severe reverses at the hands of Islamic movements, and so it has dropped the old military tactics and adopted more sophisticated political and cultural ones-and this is what led the British to sponsor The Satanic Verses. But the Islamic Republic would not abide this plot, and therefore broke off relations with the United Kingdom. A Tehran daily suggested that the break could easily last "at least a decade."

In retaliation, the British government closed down the Iranian consulate in Hong Kong and expelled nine Iranians resident in the United Kingdom. The Foreign Office also urged British nationals to stay away from Lebanon. Further, the foreign secretary, using his strongest language since the controversy began, called the Iranian government a "deplorable regime" and (for the first time) condemned its recent "mass exterminations."

Two unusual features characterized these diplomatic moves. First, both the British and the Iranian governments could count on exceptionally wide domestic support for their actions, including nearly unanimous parliamentary backing. Second, for all the animosity between the two states, neither side made a single move to interfere with existing trade relations. The British continued to purchase Iranian crude oil, the Iranians continued to purchase a wide array of British goods, and such official British services as the Export Credits Guarantee Department (which provides short-term cover for British exports) witnessed a "fairly busy, regular market."

The foreign ministers of the forty-four states belonging to the Organization of the Islamic Conference met on March 13-16, 1989 in Riyadh and adopted the Saudi position, not the Iranian one, on Rushdie:

The conference declared that blasphemy cannot be justified on the basis of freedom of expression and opinion. The conference strongly condemned the book The Satanic Verses, whose author is regarded as a heretic. It appeals to all members of society to impose a ban on the book and to take the necessary legislation to insure the protection of the religious beliefs of others.

A British official responded a day later by attempting, not to explain that freedom of speech did indeed encompass blasphemy, but to disassociate his government from Rushdie. Foreign Office Minister William Waldegrave went on the BBC's Arabic Service to explain:

I would like to put on record that the British Government well recognizes the hurt and distress that this book has caused, and we want to emphasize that because it was published in Britain, the British Government had nothing to do with and is not associated with it in any way. ... What is surely the best way forward is to say that the book is offensive to Islam, that Islam is far stronger than a book by a writer of this kind.

Radio Tehran read this statement as a British acknowledgment that the book includes blasphemous passages, and counted this admission as a major step forward from the Howe and Thatcher statements. It made, however, no concessions in return.

Exactly one month after the decision to withdraw top diplomats of the EEC from Iran, the foreign ministers met again and decided, under Greek, Irish, and Italian pressure, to send them back. Khomeini described the Europeans as returning in "shame, abjectness, and disgrace, regretting their deed." Lamely, the French Foreign Ministry called this an "exaggeration."

X. Conclusion

'Ali Akbar Hashemi-Rafsanjani, speaker of the Iranian parliament, observed that the Rushdie affair is "one of the rarest and strangest events in history," and he is right. Several aspects of the Rushdie incident are unprecedented.

Never has a book been so much the heart of an international crisis. Never have so many governments waited so anxiously for the peaceable moves of a private writer. The absurdity of the situation was caught by a cartoon in Le Monde which showed Rushdie at his typewriter, surrounded by fifteen harried bobbies keeping an eye on him; one of the policemen barks into the walkie-talkie, "Close the airports!! He wants to write volume two!!!"

Similarly, never before has there been a human rights case that crossed boundaries in this fashion. "Other despots have banned books and outlawed thoughts," observed Hendrik Hertzberg. "What is unique and unprecedented about Khomeini is the global ambition, and the threatened global reach, of his censorship-by-threat. He has created the first planetary civil liberties case. This is his distinctive contribution to the history of tyranny." And the West's reaction, when confronted by the first planetary civil liberties case, was to back down as far as it legally could.

Bibliography: In addition to my 1990 book, The Rushdie Affair, here are my articles on the Rushdie affair and its aftermath:

- "The Ayatollah, the Novelist [Salman Rushdie], and the West." Commentary, June 1989.

- "[Salman Rushdie Affair:] How to Sell a Book and Live Dangerously." Philadelphia Inquirer, August 24, 1989.

- "'Satanic' Edict Still Bedevils Free Speech." Wall Street Journal, 26 September 1989.

- "Rushdie Fails to Move the Zealots." Los Angeles Times, December 28, 1990.

- "Mr. Clinton's Meeting with Salman Rushdie Sent the Wrong Signals." Washington Times, December 8, 1993.

- "[Hebron Pig Poster Incident:] How Clinton Adheres to the 'Rushdie Rules'." Forward, .

- "Salman Rushdie's Delusion, and Ours [about His Safety]." Commentary, December 1998.

- "Is Salman Rushdie Now Safe?" DanielPipes.org, June 5, 2004.

- "Intimidating the West, from Rushdie to Benedict." New York Sun, September 26, 2006.

- "Salman Rushdie and British Backbone." New York Sun, June 26, 2007.

- "'Rushdie Rules' Reach Florida." Washington Times, September 21, 2010.

- "Two Decades of the Rushdie Rules." Commentary, October 2010.

And book reviews:

- Lisa Appignanesi and Sara Maitland, eds., "The Rushdie File." Orbis, Winter, 1990.

- Malise Ruthven, "A Satanic Affair: Salman Rushdie and the Rage of Islam." Orbis, Summer, 1990.

- "Pour Rushdie: Cent intellectuels arabes et musulmans pour la liberté d'expression. Middle East Quarterly, June 1994.

- Mehdi Mozaffari, "Fatwa: Violence and Discourtesy." Middle East Quarterly, March 2000.