In the West, conversions involving Islam appear to be a one-way street in its favor. Famed new believers include Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Muhammad Ali, Malcolm X, Keith Ellison, and Sinéad O'Connor, as well as flamboyant flirts like Prince Charles, Michael Jackson and Lindsay Lohan. Also, there are about 700,000 African-American converts and their descendants.

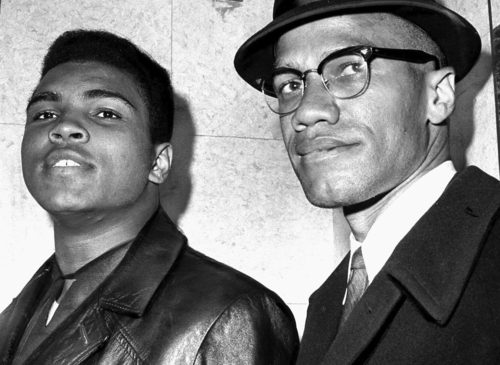

Muhammad Ali and Malcolm X in New York City in 1964. |

To begin with, some numbers: In France, around 15,000 Muslims convert annually to Christianity, according to a 2007 estimate. About 100,000 American Muslims abandon Islam each year, reports a 2017 Pew Research Center survey. This amounts to 24 percent of all Muslims in the United States, with Iranians disproportionately represented. These numbers roughly counterbalance those of non-Muslims converting to Islam.

Reasons for leaving Islam vary: Pew finds 25 percent of American ex-Muslims have general issues with religion, 19 percent with Islam in particular, 16 percent prefer another religion, and 14 percent cite reasons of personal growth. Slightly more than half of those leaving (55 percent) abandon religion entirely and slightly less than a quarter (22 percent) convert to Christianity.

Apostates challenge Islam in three main ways: publicly leaving Islam, organizing with other ex-Muslims, and rejecting the Islamic message.

First, overtly apostatizing is a radical act that can lead to execution in a Muslim-majority country like Iran. Even in the West, it meets with rejection by families, social ostracism, humiliation, curses, threats, reprisals, and violent attacks. Accordingly, conversions out of Islam tend to be cautious or hidden, as in the cases of British author Salman Rushdie and pop star Zayn Malik. Carlos Menem of Argentina minimized his apostasy; Barack Obama elaborately denied his.

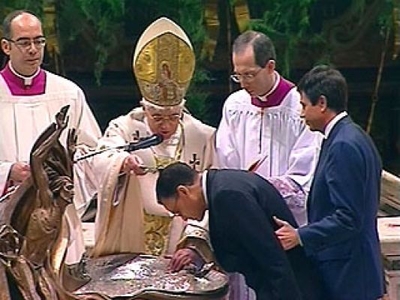

Nonetheless, some converts make a point of leaving publicly, encouraging others by their example. Ibn Warraq wrote Why I Am Not a Muslim. Nonie Darwish and Ayaan Hirsi Ali wrote books about becoming "infidels." The journalist Magdi Allam converted at the hands of Pope Benedict in a widely televised ceremony.

Pope Benedict personally converted Magdi Allam in 2008. |

Second, ex-Muslims living in the West do something inconceivable in Muslim-majority countries: starting with Germany's Central Council of Ex-Muslims (Zentralrat der Ex-Muslime) in 2007, they have organized dozens of public ex-Muslim organizations to provide mutual support, polish arguments, raise troublesome issues (such as female genital mutilation), and fight Islamism.

Brother Rachid's U.S.-based television show has reached many Arabic-speaking Muslims. |

Converting, organizing, proselytizing: thus do vocal ex-Muslims in the West send shock waves to their countries of origin especially, where Islam is historically protected by custom and law from any criticism or even irony, where repression and punishment render anti-Islamic views illegal. Anxious authorities ban Christian proselytizing and censor ex-Muslim voices. They even connect this movement to a "Zionist conspiracy," though such efforts tend to be as ineffective as they are platitudinous.

A poignant anonymous letter from Karachi, Pakistan, to the Observer during the peak of the Satanic Verses controversy in 1989 shows the inspiration of one ex-Muslim's message. The letter writer replied to Ayatollah Khomeini's call to murder Salman Rushdie because the novelist wrote disrespectfully about Muhammad:

mine is a voice that has not yet found expression in newspaper columns. It is the voice of those who are born Muslims but wish to recant in adulthood, yet are not permitted to on pain of death. Someone who does not live in an Islamic society cannot imagine the sanctions, both self-imposed and external, that militate against expressing religious disbelief. ... Then, along comes Rushdie and speaks for us. Tells the world that we exist—that we are not simply a mere fabrication of some Jewish conspiracy. He ends our isolation.

With passion and a unique authority, ex-Muslims push believers to think critically about their faith. Their efforts have substantially contributed to a general decline in religiosity now conspicuously underway among Muslims, especially among the youth. As the Economist summarizes a recent Arab Barometer survey, "Many [Arabic-speaking Muslims] appear to be giving up on Islam."

Thus do boisterously opinionated ex-Muslims challenge their birth religion, helping both to modernize it and reduce its grip. Their role has only just begun.

Mr. Pipes (DanielPipes.org, @DanielPipes) is president of the Middle East Forum.

Aug. 17, 2020 update: Julian Göpffarth and Esra Özyürek offer a sophisticated left-wing view of the role of ex-Muslims among civilizationist parties in Europe at "Spirit or Reason? Muslim Public Intellectuals in the German and European Far Right."

Aug. 18, 2020 update: In a silly letter to the editor, Ralph M. Coury of Fairfield University admonishes me for assuming that ex-Muslim must become expatriates to be important. But I made no such assumption. Rather, I limited my topic to ex-Muslims in the West; "In the West" happen to be the article's first three words.

I am quite aware of the individuals he mentions who lived in the Middle East: Taha Husayn, Adunis, Sadiq al-Azm. (Indeed I met the first and third of them.) They just happen not to be the topic in this article.