Consider three episodes over a century:

In March 2019, the Syrian jihadi groups Hayat Tahrir al-Sham and National Liberation Front clashed, leading to about 75 deaths;[1] two months later, they joined forces to fight Syria's central government.[2] By October, they were fighting each other again.[3]

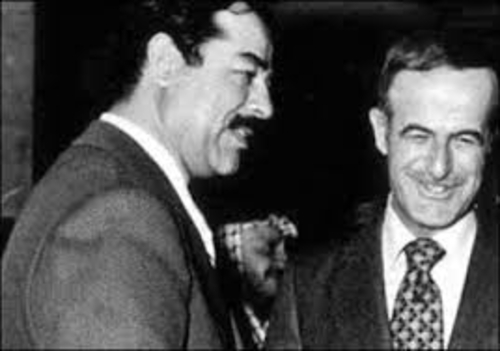

In 1987, Saddam Hussein and Hafez al-Assad, the dictators of Iraq and Syria, were mortal enemies; yet, when they met at an Arab League summit, they "were seen walking together and joking."[4]

Saddam Hussein (L) and Hafez al-Assad getting along. |

During World War I, Armenians and Azeris fought each other and then, in what historian Tadeusz Swietochowski calls a "switch from killing to embraces. ... remarkably, in the midst of the intercommunal fighting, there began to circulate the idea of Transcaucasian federalism, the regional union of Georgians, Armenians, and Azerbaijanis" which evolved into the Transcaucasian Federation of 1921-22.[5]

As these examples suggest, kaleidoscopic coalitions and enmities are one of the Middle East's most distinctive political features. Only full-time specialists can keep track of civil wars in Libya, Yemen, and Syria – and they rely on complex tools.[6]

This pattern of fighting and hugging is well known to Middle Easterners. The PLO's Khalid al-Hasan called it "Arab nature," explaining that "Arab history has never known a final estrangement. It is full of agreements and differences. When we differ and then grow tired of differing, we agree. When we grow tired of agreeing, we differ."[7] Faruq Qaddumi, another PLO leader, found that "Attitudes in the Arab region change like desert sands in the wind – building up and then swiftly disappearing."[8] Hussein Sumaida, a refugee from Saddam Hussein's Iraq, used the same analogy: "There are no such things as allies in the Middle East. There are only shifting sands."[9]

Abd al-Hamid Zaydani, an Islamist leader in Yemen, put it succinctly: "Either we unite, or we fight."[10] Barzan Ibrahim at-Takriti, Saddam Hussein's brother, agreed: "Either we have full unity, or a general destructive war will be the only alternative." The usual political relationship, he said, "begins with hugs and kisses and ends up in disputes and war."[11]

Two primary patterns stand out: Palestinian politics and other enemies joining together against a common foe, then falling out again.

Jordan's King Hussein (L) and Yasir Arafat, best of friends in 1993. |

In mid-1992, Yasir Arafat's and George Habash's militias fought each other in Lebanon; but when the two leaders met in Amman in October 1992, the two literally embraced each other.[15] The Palestinian Authority sometimes cooperates with Israel on security matters and at other times resorts to incitement and murder. Such reversals particularly affected Arafat; in Barry Rubin's description, he "always remembered that the Arab leader who shot at him one day might become the one he kissed another, and the reverse as well."[16] Hamas and the Palestinian Authority repeatedly alternated between killing each other (most especially when Hamas violently expelled the PA from Gaza in 2007) and trying to combine their forces versus Israel.

Other enemies joining together: Islamists who had fought Saddam Hussein supported him after his 1990 invasion of Kuwait. Likewise, Tehran had been at war with him just two years earlier but now made common cause against a shared common enemy, the United States. Turkey's leader, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, insults with abandon former allies such as the leaders of France, Germany, Syria, and Iran. Should Iranian aggression cease, this logic could suddenly abort the Abraham Accords.

What explains this extreme political volatility? As brilliantly explained by Philip Salzman,[17] it results from the tribal ethos summed up by the well-known adage, "I against my brother, I and my brothers against my cousins, I and my brothers and my cousins against the world." This premodern mentality encourages abrupt changes. Until tribalism dies out, Middle Eastern politics will continue to be characterized by amorality, fluidity, temporariness, inconsistency, and contradiction.

Mr. Pipes (DanielPipes.org) is president of the Middle East Forum. © 2021 by Daniel Pipes. All rights reserved.

[1] Agence France-Presse, "Syria rebel-jihadist clashes kill dozens: monitor," France24, 1 March 2019.

[2] Anchal Vohra, "Turkey-backed fighters join forces with HTS rebels in Idlib," Al Jazeera, 22 May 2019.

[3] Jared Szuba, "Turkey-backed rebels announce unification under 'Syrian National Army'," The Defense Post, 4 October 2019.

[4] Elie A. Salem, Violence and Diplomacy in Lebanon: The Troubled Years, 1982-1988 (London: I. B. Tauris, 1995), p. 249.

[5] Tadeusz Swietochowski, "Azerbaijan: Between Ethnic Conflict and Irredentism," Armenian Review, Summer/Autumn 1990, pp. 47, 37.

[6] For example, the Washington Institute for Near Eastern Policy's "Yemen Matrix: Allies & Adversaries."

[7] Radio Monte Carlo, 11 December 1984.

[8] Quoted in Al-Majalla, 18 June 1986.

[9] Hussein Sumaida, with Carole Jerome, Circle of Fear: My Life as an Israeli and Iraqi Spy (Washington: Brassey's, 1994), p. 75, 258.

[10] Quoted in Agence France Presse, 15 April 1990.

[11] Quoted in Al-Jumhuriya (Baghdad), cited in Babil, 9 May 1994.

[12] Quoted in Michael B. Oren, Six Days of War: June 1967 and the Making of the Modern Middle East ( New York: Oxford University Press, 2002), p. 131.

[13] As paraphrased by Barry Rubin, Revolution Until Victory? The Politics and History of the PLO (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1996), p. 37.

[14] Interviewed by Al-Hayat and reported by Agence France-Presse, 28 July 2001.

[15] Radio Monte Carlo, 8 October 1992.

[16] Rubin, Revolution Until Victory?, p. 128.

[17] In Culture and Conflict in the Middle East (Amherst, NY: Prometheus, 2008).