The fall of the shah ranks with the communist takeovers of China and South Vietnam as one of the greatest setbacks to American foreign policy since World War II. When the Ayatollah Khomeini came to power in February 1979, the United States lost a supplier of energy, a major customer, a friend in the Persian Gulf, and a strategic ally against the Soviet Union.

The fall of the shah ranks with the communist takeovers of China and South Vietnam as one of the greatest setbacks to American foreign policy since World War II. When the Ayatollah Khomeini came to power in February 1979, the United States lost a supplier of energy, a major customer, a friend in the Persian Gulf, and a strategic ally against the Soviet Union.

In the wake of this setback – and we are still ignorant of its full consequences – the actions of the Carter administration have become the focus of sharp debate. The lines of argument are already clear. Those who support Carter argue that the shah fell of his own weight; the US had neither the means nor the right to save him. Steven Cohen, former deputy assistant secretary of state for human rights, wrote in The New Republic on March 28 that the shah was the victim of "profound social and political revolutions that were decades in the making." Stresses that had been building up came to a head in 1978: economic mismanagement, political repression, social discontent, and cultural schizophrenia combined with such force that no outside power could have thwarted the Iranians from their revolutionary course. Further, those who favor the Carter administration argue that it acted honorably; even if the US lost from the changes in Iran, not attempting to undermine the revolution restored the "former reputation of the United States as a supporter of freedom, ... replacing its more recent image as a patron of tyranny."

Carter opponents stress the American role in the shah's collapse. They see the events of 1978 as fluid; the rise of the Ayatollah Khomeini was neither inevitable nor clearly preferred by most Iranians. In their view, the US's abdication of its proper role in Iran led to a disastrous loss of power in that country and to a diminishment of its credibility internationally. While Carter apologists emphasize the irresistible movement of events within Iran, the opponents lay stress on foreign influences – not just of the US, but also of the Soviet Union and the PLO.

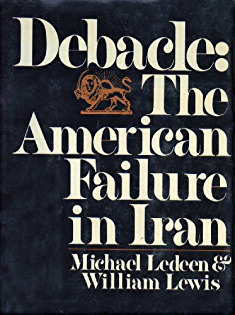

Michael Ledeen and William Lewis have chosen a title which leaves no doubt where they stand in this controversy. The United States, they argue, had such a powerful role to play in Iran that even its attempt not to act had huge repercussions. President Carter wanted to stay clear of involvement. As he put it in a press conference on December 7, 1978, barely a month before the shah left Iran permanently:

We have never had any intention and don't have any intention of trying to intercede in the internal political affairs of Iran. We primarily want an absence of violence and bloodshed, and stability. We personally prefer that the shah maintain a major role in the government, but that's a decision for the Iranian people to make.

According to Ledeen and Lewis, all this was "a self-deception." The United States had to play a role, "for the Iranian people, like those in every small country dependent on the policies of the superpowers, were particularly sensitive to anything that looked like a change in policy on the part of the American government." There was no opting out; in itself, taking no action had enormous impact on both the shah and his opponents, convincing them all that President Carter had abandoned the shah (as it turns out, an utterly wrong conclusion). Stress on human rights and on differences between the US and Iranian governments further confirmed for Iranians that Washington had forsaken the shah.

The authors single out Carter's human rights policy for attack, arguing that most of all it confused the Iranians (and other allies). They believe that Carter's officials who were intent on introducing moralism into American foreign affairs probably "had not thought through the international consequences of the presidential rhetoric. ... [E]ither the administration was serious, in which case some form of 'linkage' would have to be adopted" or else its words could be dismissed as mere bombast. For linkage to work, human rights issues could be pressed only against countries over which the United States exerted influence – our allies. What pressure short of military intervention could we exercise on the most vicious violators of human rights in Cambodia, Vietnam, or Uganda?

As a result, "the full force of the human rights advocates came to bear on authoritarian regimes that were considered reactionary, and that were tied more or less closely to the United States." Relations with such countries as South Korea, Nicaragua, and Iran worsened, confusing their leaders.

It appeared to many nations that the United States was abandoning its traditional policy of containment of Soviet expansion in favor of a new sort of moral isolationism. ... [T)he impression from the outside was of an administration that was withdrawing from world affairs, that imposed arbitrary standards on its allies and would-be allies, and that was capable of sudden dramatic turnabouts in its relations abroad. Above all, many foreign leaders were baffled by the apparent abandonment of traditional concepts of national self-interest.

If leaders were baffled, opposition movements were emboldened; American politics inspired the shah's enemies to act by the end of 1977. They had shaken the regime within a few months, yet Washington paid no attention. One reason for this was the dismal performance of American intelligence services. Ledeen and Lewis report that by June 1978 the Israelis had concluded that the shah was doomed and the French predicted in the spring of 1978 that the shah would be gone within the year, but the Americans ignored these reports and continued to believe in the shah's strength. A Defense Intelligence Agency intelligence appraisal of September 28, 1978, declared that "the shah is expected to remain actively in power over the next 10 years." (He fled Iran on January 16, 1979.) Unbelievably, Washington did not know about Mohammad Reza Pahlavi's terminal cancer; nor did it understand his character (he was counted on to be far more ruthless than was the case) or that of Khomeini (who was counted on to be manipulable by the politicians). In all, "the U.S. government was always at least one step behind the realities of the Iranian revolution."

Conflicting policies within Washington exacerbated the difficulty of dealing coherently with Iran. Leaks to the press, special counselors, and last-minute envoys, Brzezinski-Vance conflicts, human rights zealots, and a basic reluctance to appreciate "the potentially catastrophic dimensions of the Iranian crisis" all contributed to the mess. For example, during January 1979, the US had two ranking representatives in Tehran, the ambassador and a presidential emissary. "In one of the more bizarre scenes in recent American diplomatic history, the two men would dine together and discuss the day's developments. After dinner and brandy first one, then the other would call Washington with almost diametrically different assessments." Even more than these obstacles to coherent policy, "the basic problem throughout the crisis was that the President was notable for his absence," uninterested in the problem and unwilling to set down the outlines of US policy to guide his aides.

In keeping with their interest in the role of outside forces, Ledeen and Lewis also note the Soviet and Palestinian connections. A Persian language radio station had been operating clandestinely just inside the Soviet border with Iran for 20 years; in contrast to the official Soviet policy of mild support for the shah, the "National Voice of Iran" viciously attacked him. "On some occasions the correspondence between the words of the National Voice and the actions in the streets of Iran was impressive." For example, the first seizure of the US embassy in Tehran took place on February 14, 1979, within hours after the station announced that the police files of SAVAK had been transferred to it.

The Palestine Liberation Organization had an even more central role. For while Khomeini's "triumph rested in the last analysis on the support of the Iranian people," it also depended on an organization. Here the PLO had a vital role in structuring the shah's opposition, training it, providing it with arms and international contacts. The forces which brought Khomeini to power had always been anarchic in the past but he was able to order them "because he was able to enlist non-Iranian forces in his struggle."

Many tantalizing, undocumented points crop up in Debacle. I was not aware that every Israeli prime minister has visited Tehran. Ledeen and Lewis report that the shah subsidized deposed monarchs; that Khomeini used assassination against other ayatollahs to further his bid to become Iran's supreme religious leader; that Yasser Arafat appeared at the funeral of Ali Shari'ati, a radical Iranian thinker about Islam and society. I did not know that the shah asked French president Giscard D'Estaing not to sign an order expelling Khomeini from France in mid-November 1978, or that the shah refused to give Iranian military leaders permission to stage a military coup after his departure from the country.

With clarity and logic, Ledeen and Lewis demonstrate two points: the vital importance of America's role during the Iranian revolution and Washington's disarray in coping with this issue. Their argument is forceful, yet I finished Debacle with an uneasy feeling. Its authors show a greater understanding of American interests than the combined wisdom of the Carter administration; I salute their political skills. But their book betrays the same cultural attitudes that have repeatedly undermined US interests in Iran and elsewhere.

Despite four decades as a leading international power, America still lacks rapport with alien customs and mentalities. US foreign policy specialists often show a distressing lack of interest or understanding in the rest of the world. For example, they viewed Iran as a characterless cipher: a less developed country, an oil exporter, an arms market, a strategic ally – not as a nation whose history, religion, and social mores make it unique. The specialists concentrated on foreign policy matters to the exclusion of foreign expertise.

Uninterested in Iran but fascinated by the process of policy formulation in Washington, Ledeen and Lewis fuel the wrong debate. We gain little from a battle over "who lost Iran"; rather, what we need is serious inquiry into the causes of the Iranian uprising – the feud between Abbas Hoveyda and Jamshid Amouzegar (and not that between Brzezinski and Vance), the generals' attitude toward the shah, the danger of mutiny in the army ranks, the sources of Khomeini's support, and the struggle between the factions that brought Khomeini to power.

Even more, we need to recognize the American inability to shed our own cultural context and pay attention to the ways of other peoples. Iranians are not just poorer than Americans; they differ from us in a myriad of important ways. Something can be salvaged from the American failure in Iran if it spurs the foreign policy establishment to take other cultures more seriously.

Daniel Pipes, associated with the University of Chicago, is the author of Slave Soldiers and Islam, just published by Yale University Press.