I am not much of a cook. I don't play ball games with distinction. My public speaking abilities are indifferent. My income is modest. And my mediocrity in all these realms is just fine by me.

I am not much of a cook. I don't play ball games with distinction. My public speaking abilities are indifferent. My income is modest. And my mediocrity in all these realms is just fine by me.

That's because the one thing I do take pride in is my writing. I write about history and politics, mostly concerning the Middle East. I try hard to reach both a specialist audience (people who like me spend their working hours on these issues) and a non-specialist one (everyone else).

Although I have published some ten books and hundreds of articles, writing remains for me a difficult enterprise. As anyone who has been a student knows, getting one's thoughts down on paper is hard to do. Yes, it does get somewhat easier with experience, but not by much, perhaps because it involves turning the three-dimensional chaos of the world into the neat order of two dimensions on paper. Writing always requires concentration and purpose and there is no way to avoid the first draft, that sloppy and ungainly effort to order one's thoughts. Nor can I avoid the many subsequent drafts and rereadings, sometimes a dozen in all, or even more.

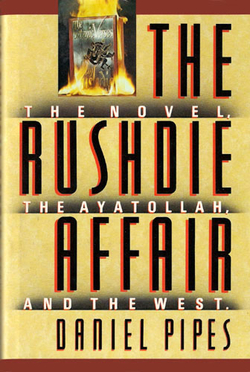

The only time writing is relatively easy is on those rare occasions when I know in advance what I plan to say, and putting it down becomes more of a secretarial task than a creative one. This sometimes happens with a newspaper article, say, and a thousand words spews out in just an hour or so. Usually, this happy experience follows on repeated discussions of a topic, when I have figured out what I think. But on rare occasions the same can apply to a magazine article or even a book. My most memorable experience along these lines took place in 1989: Ayatollah Khomeini pronounced his edict of death against Salman Rushdie on February 14 and I had a full-length book on this, explaining its background and implications, by the end of May 1989. I remember that time fondly as a singular moment of white heat. I assume, sadly, that it was a one-time episode that will not recur.

The only time writing is relatively easy is on those rare occasions when I know in advance what I plan to say, and putting it down becomes more of a secretarial task than a creative one. This sometimes happens with a newspaper article, say, and a thousand words spews out in just an hour or so. Usually, this happy experience follows on repeated discussions of a topic, when I have figured out what I think. But on rare occasions the same can apply to a magazine article or even a book. My most memorable experience along these lines took place in 1989: Ayatollah Khomeini pronounced his edict of death against Salman Rushdie on February 14 and I had a full-length book on this, explaining its background and implications, by the end of May 1989. I remember that time fondly as a singular moment of white heat. I assume, sadly, that it was a one-time episode that will not recur.

Despite its difficulty for me, I focus on writing for three main reasons. First, it is consequential. Writing moves the world. Virtually every idea any one of us has ever had ultimately derives from a text someone once wrote. Spiritual life, political ideology, technology, notions of romance - they all derive from words on paper (or, latterly, computer screen). Every newscast and movie flows from the written word. So has it been for millennia and so will it remain even in this era of multimedia and blossoming new technologies. The only way to flesh out an idea, make it permanent, and perfect its expression remains the written word. When I write, I feel I have a chance to participate in this deeply significant human undertaking.

Second, writing is rewarding. Seeing one's name in print, it cannot be denied, is a pleasure. It's partly a matter of ego gratification, partly a satisfaction of memorializing one's thoughts and having them made permanent in a polished form. But writing also rewards me in a more material sense, being the fulcrum of my career. Nearly all the opportunities I have result from writing. Newspaper columns lead to national television, magazine pieces win invitations to visit distant places, scholarly articles bring business consultancies, and books land me in conferences.

Finally, I write because I feel a wish to express myself. No matter how many times I might repeat myself on some issue - say the Arab-Israeli conflict or the dangers of fundamentalist Islam - my thoughts remain ephemeral until I put them down. The written essay implies a rigor that requires me to make my views coherent.

And so, while there are many times when I would rather watch television or laze off, I usually pull myself together and make myself write. It's not always fun but it is always worthwhile.