The revolt in Syria offers great opportunities, humanitarian and geo-political. Western states should quickly and robustly seize the moment to dispatch strongman Bashar al-Assad and his accomplices. Many benefits will follow when they reach their appointed dustbin of history.

Syrians pulling down pictures of al-Assads, Bashar (left) and his father Hafez. |

But Bashar's main role internationally is serving as Tehran's premier ally. Despite Westerners usually seeing the Syrian-Iranian alliance as a flimsy marriage of convenience, it has lasted over thirty years, enduring shifts in personnel and circumstances, due to what Jubin Goodarzi in 2006 called the two parties' "broader, long-term strategic concerns derived from their national security priorities."

The Syrian intifada has already weakened the Iranian-led "resistance bloc" by exacerbating political distancing Tehran from Assad and fomenting divisions in the Iranian leadership. Syrian protesters are burning the Iranian flag; were (Sunni) Islamists to take power in Damascus they would terminate the Iranian connection, seriously impairing the mullah's grandiose ambitions.

Kurds protesting for citizenship in Qamishli, Syria, in April 2011. |

Turmoil in Syria offers relief for Lebanon, which has been under the Syrian thumb since 1976. Similarly, a distracted Damascus permits Israeli strategists, at least temporarily, to focus attention on the country's many other foreign problems.

Domestic: In a smug interview discussing developments in Tunisia and Egypt, and just weeks before his own country erupted on March 15, Bashar al-Assad explained the misery also facing his own subjects: "Whenever you have an uprising, it is self-evident that to say that you have anger [which] feeds on desperation."

The word desperation nicely summarizes the Syrian people's lot; since 1970, the Assad dynasty has dominated Syria with a Stalinist fist only slightly less oppressive than that of Saddam Hussein in Iraq. Poverty, expropriation, corruption, stasis, oppression, fear, isolation, Islamism, torture, and massacre are the hallmarks of Assad rule.

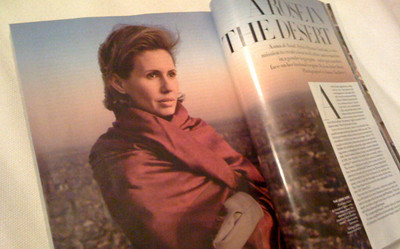

Vogue's puff-piece on the wife of Bashar al-Assad in its March 2011 issue. |

One potential danger resulting from regime change must be noted. Expect not a relatively gentle coup d'état as in Tunisia or Egypt but a thorough-going revolution directed not only against the Assad clan but also the Alawi community from which it comes. Alawis, a secretive post-Islamic sect making up about one-eighth of the Syrian population, have dominated the government since 1966, arousing deep hostility among the majority Sunnis. Sunnis carry out the intifada and Alawis do the dirty work of repressing and killing them. This tension could fuel a bloodbath and even civil war, possibilities that outside powers must recognize and prepare for.

As impasse persists in Syria, with protesters filling the streets and the regime killing them, Western policy can make a decisive difference. Steven Coll of the New Yorker is right that "The time for hopeful bargaining with Assad has passed." Time has come to brush aside fears of instability for, as analyst Lee Smith rightly observes, "It can't get any worse than the Assads' regime." Time has come to push Bashar from power, to protect innocent Alawis, and to deal with "the devil we don't know."

Mr. Pipes, director of the Middle East Forum and Taube distinguished visiting fellow at the Hoover Institution, is the author of three books on Syria.

May 24, 2011 addendum: For additional thoughts that could not fit into this column, see my weblog entry, "More on Regime Change in Syria."

Dec. 8, 2024 update: The fin de régime finally came today, 13½ years later, and when no one anymore expected it.