David Hume (1711-76). |

In search of an answer, I located groaning shelves of books and articles on the English national character, many written by distinguished figures. Sadly, though, their combined wisdom amounts to a massive contradiction.

The eminent historian Mandell Creighton got me started with the observation that "the English were the first people who formed for themselves a national character." He then defined its dominant motive "to have been a stubborn desire to manage its own affairs in its own way, without any interference from outside."[2]

Many agree with this notion of an independence-loving English people. John Stuart Mill, the liberal philosopher, noted "how repugnant to the English character is anything like bluster" which, rather than intimidate it, raises its "dogged determination ... not to be bullied."[3] Three-time UK prime minister Stanley Baldwin praised his co-nationals: "The Englishman is made for a time of crisis, and for a time of emergency. He is serene in difficulties but may seem to be indifferent when times are easy."[4] David Cameron, a future prime minister, defined Britishness as "freedom under the rule of law."[5]

The 1971 play, "No Sex Please, We're British," became a popular movie. |

Speaking of the French, novelist Honoré de Balzac called the Englishman noble.[11] Spanish writer Salvador de Madariaga saw him as a man of action.[12] Belgian Maciamo Hay deemed him "independent-minded, polite, critical, moody, class-conscious, polarised, practical-minded, entrepreneurial, humorous, reserved."[13] American philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson focused on "pluck."[14] American historian Henry Steele Commager called him "so prosaic, so stolid, so materialistic."[15] Focus groups of foreigners repeatedly returned to three words: reserved, uptight, and snobbish.[16]

Middle Easterners generally have a low opinion of the Ingliz. An Ottoman-era ditty found him "irreligious."[17] Jamal ad-Din al-Afghani, an early Islamist, held that he "is little of intelligence, great of perseverance, ambition, greed, stubbornness, patience, and haughtiness."[18] Iranian author Jahangir Amuzegar announced that the British are "cold, crafty, self-controlled, deferential."[19] M. Sıddık Gümüş a Turkish conspiracy theorist, called them "a conceited and arrogant people."[20]

Looking at the larger picture, writing in 1955, Gorer found that the" fundamentally English character has changed very little in the last 150 years, and possibly longer."[21] In contrast, historian Peter Mandler reviewed English ideas about their national character in the era 1800-2000 and found that these changed continuously.[22]

Looking at the larger picture, writing in 1955, Gorer found that the" fundamentally English character has changed very little in the last 150 years, and possibly longer."[21] In contrast, historian Peter Mandler reviewed English ideas about their national character in the era 1800-2000 and found that these changed continuously.[22]

Together, these accounts tell me that the English are (contradictorily) serene and moody; brotherly and conceited; fair and greedy; haughty and deferential; hypocritical and noble; stolid and humorous. Such a string of opposites, needless to say, says nothing at all. It brings to mind an astrology forecast that predicts joy and misery tomorrow, as well as serenity and tumult, gain and loss.

Perhaps that's the way it must be. Daniel Defoe wrote in 1701 of "from a mixture of all kinds began / That heterogeneous thing, an Englishman."[23] In 2004, journalist Amelia Hill dismissed the whole effort: "bar the white cliffs and the bad weather, nothing is forever England and, however old the quest for the essence of Englishness, the hunt is a bogus one."[24]

The white cliffs of Dover. |

Hume, paradoxically, goes farthest, denying the topic's very validity: "The English, of any people in the universe have the least of a national character, unless this very singularity may pass for such."[25] And if that was true in 1748, how much truer today, in the aftermath of large-scale immigration.

With this, my impressionistic survey grinds to a halt, leaving me befuddled. Sadder and no wiser, I leave the search for English national character to return that easier topic I usually study, the Middle East.

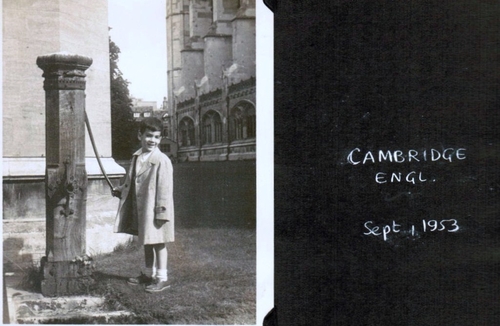

Mr. Pipes (DanielPipes.org, @DanielPipes), president of the Middle East Forum, first visited England in 1953. © 2020 by Daniel Pipes. All rights reserved.

Daniel Pipes at the King's College Chapel pump, when it still had a handle, Cambridge, England, in September 1953. |

Jan. 21, 2021 addenda: Additional quotes that did not make it into the article.

— Daniel Defoe, "The True Born Englishman" (1701):

A true Englishman 's a contradiction,

In speech an irony, in fact a fiction.

— Thomas Moses Foote, National Characteristics. An Address Delivered before the Literary Societies of Hamilton College, July 24, 1848. (Buffalo: Steam Press of Jewett, Thomas, 1848), p. 26: The English

have become a distinct, characterized race, just as we see a distinct breed of animals produced by crossing.

— William Dalton Babington, Fallacies of Race Theories as Applied to National Characteristics (London: Longmans, Green, 1895), p. 4:

One writer points out what a kindly person the Englishman is, how brave and wise, how steadfast and true, how prudent and pious, A French writer will very probably hold quite another view of perfide Albion. The Irish patriot seems to think the Saxon so bad, that the sooner he reaches the perdition to which he is hurrying the better for everybody.

— Rudyard Kipling, England and the English (London: Society of St. George, 1920), p. 2:

the Englishman is like a built-up gun barrel, all one temper though welded of many different materials, and he has strong powers of resistance.

— Aldous Huxley, "Sir Christopher Wren" (1928):

That an Englishman should be a very great plastic artist is always rather surprising. Perhaps it is a matter of mere chance; perhaps it has something to do with our national character—if such a thing really exists.

— Kate Fox, Watching the English: The Hidden Rules of English Behavior (2004):

I found that Women's Institute members and bikers, and other groups, all behave in accordance with the same unwritten rules — rules that define our national identity and character. I would also maintain, with George Orwell, that this identity "is continuous, it stretches into the future and the past, there is something in it that persists, as in a living creature."

— Roland White, review of Watching the English, Times of London, Apr. 25, 2004:

When the first Angle immigrants arrived in fifth-century Britain and politely set up neat, semi-detached settlements around the River Humber, it cannot have been long before a scribe produced the first illuminated scroll that asked: "What are the qualities of a typical Anglishman?" We seem to have been asking the same question ever since.

George Orwell produced a list of essential Englishness that included the public-school system, clubs, codes, conformity. Five years ago, in The English, Jeremy Paxman preferred irony, mistrust of foreigners, an obsession with breasts, a love of quizzes and crosswords, the phrase "I know my rights" and the modest self-confidence that produced the famous newspaper headline "Fog in channel — Continent cut off."

Feb. 3, 2021 update: Just days after publication, a "huge section" of Dover's white cliffs fell into the sea and was captured on film.

Apr. 18, 2021 update: Also writing in The Critic, Graham Cunningham asks why "has Englishness failed to garner its own version of the self-flattering national mythology of so many other nations?" He then amusingly answers his question.

May 14, 2022 update: Lionel Shriver provides "My list of Britain's national character flaws."

May 15, 2023 update: UK Home Secretary Suella Braverman:

We cannot have immigration without integration. And if we lack the confidence to promote our culture, defend our values, and venerate our past, then we have nothing to integrate people into. We have a nation, but more than that, we have a national character to conserve.

June 17, 2023 update: In a humorous rant, Lucy Morgan explains in "I can't stand British summers, and I know I'm not the only one" that

Our national character was formed under a perennially grey sky and remains hunched against the drizzle still. The sun will never shine in our souls.

Sep. 27, 2024 update: Kathleen Stock writes of the "predictable facets of the national character: a love of small pleasures, emotional repression, argumentativeness, and all the rest of it."

Apr. 20, 2025 update: The Critic takes a third crack at this topic, this time focused on the British, not English, national character, and with a much more serious purpose than the prior inquiries. Sam Bidwell's "What really makes us British? There is more to our national identity than warm beer and fish and chips" dismisses "British values," parliament and the crown, and Christianity as key characteristics. Instead, he finds "innumerable distinguishing features, many of which have endured through centuries of constitutional, religious, and economic change."

For at least 750 years, the English have been a nation of small families, who buy and sell land, and who marry relatively late. Our parents expect us to leave home for paid work, we owe relatively few obligations to our extended kin, and we have relatively high freedom to select our own spouses. This low-obligation family culture also enables an unusual degree of economic mobility, and it encourages a culture of bourgeois saving and property ownership. After all, if we are tied to neither our parents nor the land, it becomes much easier to migrate internally in search of improved prospects. ...

This high degree of internal movement has been coupled with a relatively low level of external migration. Save for a few Norman nobles, a handful of Huguenots, and a smattering of Flemish wool merchants, the population of the British Isles has remained remarkably stable for the past millennium or so — that is, until the second half of the 20th century. The relative stability of our population has enabled our norms to work on their own terms, ensuring cohesion despite domestic population churn.

He goes on to deduce from these basics the special British interpersonal relationships, their means of settling disputes, its "flourishing civic society," and the intellectual tradition of empiricism. He sums up the British national character as

An individuated, mobile population, which prefers meritocracy to nepotism, and which conducts itself according to pre-agreed norms that allow strangers to place their trust in one another.

A typical English hotel and The Critic's illustration for this article. |

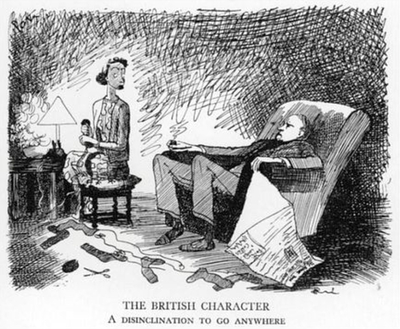

A reassuring stereotype. |

[1] David Hume, "Of National Characters," The Philosophical Works (Edinburgh: Black and Tait, 1826,), vol. 3, p. 234.

[2] Mandell Creighton, The English National Character (London: Henry Frowde, 1896), .pp. 8, 11. Conversely, Krishan Kumar, The Making of English National Identity(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003) sees Englishness as secondary to Britishness and its imperial ambitions.

[3] John Stuart Mill, The Collected Works of John Stuart Mill, ed. John M. Robson (London: Routledge, 1963-1991), vol. 13, pp. 459-60.

[4] Stanley Baldwin, "What England Means to Me", speech to the Royal Society of St George, 6 May 1924. Baldwin then wrote a whole book on this topic: The Englishman(London: Longmans Green & Co., 1940).

[5] David Cameron, "Speech to the Foreign Policy Centre Thinktank," The Guardian, 24 August 2005. Another British prime minister, John Major, characterized Great Britain as "the country of long shadows on county [cricket] grounds, warm beer, invincible green suburbs, dog lovers and pools fillers [soccer wagerers] and – as George Orwell said – "old maids bicycling to Holy Communion through the morning mist." See "Mr Major's Speech to Conservative Group for Europe," johnmajorarchive.org, 22 April 1993, accessed 12 December 2020.

[6] Edmund Dale, National Life and Character in the Mirror of Early English Literature (Cambridge, Eng.: At the University Press, 1907), p. 323. Paul Langford, Englishness Identified: Manners and Character 1650–1850 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001) pursues this topic in a later era.

[7] George Orwell, England Your England (London: Secker & Warburg, 1941).

[8] W. Somerset Maugham, preface, The Complete Plays, vol. 2, p. xii.

[9] Geoffrey Gorer, Exploring English Character (New York: Criterion, 1955), p. 287.

[10] Personal communication, Telegram, 12 December 2020.

[11] Honoré de Balzac, Illusions perdues (Paris: Club français du livre, 1962), vol. 4, p. 1067.

[12] Salvador de Madariaga, Englishmen, Frenchmen, Spaniards: An Essay in Comparative Psychology (London: Oxford University Press, 1928), pp. 1-8.

[13] Maciamo Hay, "What Makes English People So Typically English?" Eupedia, n.d.

[14] Ralph Waldo Emerson, English Traits (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1876), p. 102.

[15] Henry Steele Commager, "What the English Are," New York Times, 20 November 1955.

[16] Lee Glendinning, "A Typical Briton: Uptight But Witty," Guardian, 16 November 2004.

[17] Quoted in Bernard Lewis, The Muslim Discovery of Europe (New York: W. W. Norton, 1982), p. 174.

[18] Muhammad Basha al-Makhzumi, Khatirat Jamal ad-Din al-Afghani al-Husayni (Beirut: Yusuf Sadr, 1931), p. 131.

[19] Jahangir Amuzegar, The Dynamics of the Iranian Revolution: The Pahlavis Triumph and Tragedy (Albany, N.Y.: State University of New York Press, 1991), pp. 99-100.

[20] M. Sıddık Gümüş, Confessions of a British Spy and British Enmity Against Islam, 13th ed., (Istanbul: Hakīkat Kitâbevi, 2013), p. 75.

[21] Gorer, Exploring English Character, p. 286.

[22] Peter Mandler, The English National Character: The History of an Idea from Edmund Burke to Tony Blair (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006). In contrast, Arthur Bryant in The National Character (London: Longmans, Green, 1935) saw the English national character as basically stagnant.

[23] Daniel Defoe, "The True-Born Englishman: A Satyr" in The Novels and Miscellaneous Works of Daniel De Foe, vol. 5 (London: Henry G. Bohn, 1855).

[24] Amelia Hill, "The English Identity Crisis: Who Do You Think You Are?" The Guardian, June 12, 2004.[25] Hume, "Of National Characters," vol. 3, p. 235.