So reads an apparently routine Reuters story – ah, but what drama lies behind it!

Saudi wheat bites the dust. |

Over the three decades, the program massively depleted both the government's finances and water resources without ever being in any way necessary, for the farming powers never had any intention of blockading the kingdom. Also, the smuggling of wheat into Saudia became a big business (especially from nearby Egypt, where the government makes wheat available at lower-than-market prices.)

The changes will take place gradually. At this time, Saudi farmers turn out 2.5 million tons a year of durum and soft wheat, which suffices to meet domestic demand. Agriculture and finance ministries announced that government purchases of locally-produced wheat will go down by 12.5 percent annually each year for eight years, until it weans itself off the high-priced local produce in 2016. (January 9, 2008)

July 21, 2008 update: Ironically, just as the Saudis gave up on their wheat program, the jump in food prices is prompting neighboring countries to grow their own crops, Andrew Martin writes in "Mideast Facing Choice between Crops and Water":

Djibouti is growing rice in solar-powered greenhouses, fed by groundwater and cooled with seawater, in a project that produces what the World Bank economist Ruslan Yemtsov calls "probably the most expensive rice on earth." Several oil-rich nations, including Saudi Arabia, have started searching for farmland in fertile but politically unstable countries like Pakistan and Sudan, with the goal of growing crops to be shipped home. ... In Egypt, where a shortage of subsidized bread led to rioting in April, government officials say they are looking into growing wheat on two million acres straddling the border with Sudan.

Economists consider this a folly, urging Middle Eastern countries to grow low-water intensive, high-value export crops, such as produce or flowers. For such agriculture, one must turn to Israel, where

Doron Ovits, a confident 39-year-old with sunglasses pushed over his forehead and a deep tan, runs a 150-acre tomato and pepper empire in the Negev Desert of Israel. His plants, grown in greenhouses with elaborate trellises and then exported to Europe, are irrigated with treated sewer water that he says is so pure he has to add minerals back. The water is pumped through drip irrigation lines covered tightly with black plastic to prevent evaporation.

A pumping station outside each greenhouse is equipped with a computer that tracks how much water and fertilizer is used; Mr. Ovits keeps tabs from his desktop computer. "With drip irrigation, you save money. It's more precise," he said. "You can't run it like a peasant, a farmer. You have to run it like a businessman."

Israel is as obsessed with water as Mr. Ovits is. It was there, in the 1950s, that an engineer invented modern drip irrigation, which saves water and fertilizer by feeding it, drop by drop, to a plant's roots. Since then, Israel has become the world's leader in maximizing agricultural output per drop of water, and many believe that it serves as a viable model for other countries in the Middle East and North Africa.

Interestingly, despite its Israeli origins, drip irrigation has been adopted in Tunisia and Egypt.

Sep. 1, 2008 update: The Middle East Review of International Affairs has published the summary of a 2005 dissertation at the University of London by Elie Elhadj, a banker of Syrian origins, "Experiments in Water and Food Self-sufficiency in the Middle East: The Consequences of Contrasting Endowments, Ideologies, and Investment Policies in Saudi Arabia and Syria." In addition to giving an overall analysis of the Arab states' problems with food, he looks closely at the Saudi experience. Some extracts (for footnotes, see the original text):

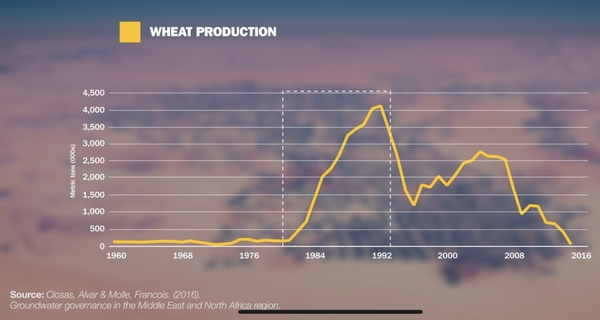

Farming is alien to desert habitat and the culture of its peoples. As Saudi Arabia became rich following the quadrupling of oil prices in 1973, however, Saudi investors were induced by huge government subsidies to import the equipment and the farm workers to implement a heavily propagated strategy of food self-sufficiency. Within 12 years, between 1980 and 1992, wheat production grew 29-fold—to 4.1 million tons--making the Saudi desert the world's sixth-largest wheat exporting country. To achieve this enormous growth, the wheat-producing areas were increased by 14-fold, to 924,000 hectares. To put 924,000 hectares in perspective, Egypt, with five times as many people, has an irrigated surface for all crops evolved over the centuries of 3 million hectares.

Beginning in 1993, under pressure from declining oil prices since the mid 1980s, the government had to scale down its wheat-growing subsidies. The budget deficits between 1984 and 1992 added up to $130 billion. Liquidity became so tight that the government had to delay (default) for a few years in honoring more than $70 billion in obligations to thousands of suppliers, contractors, and farmers. ... Within four years, by the end of 1996, 76 percent of the new wheat-growing surface was abandoned. Wheat production dropped by 70 percent. By 2000, barley production, too, dropped by 94 percent.

The estimated financial cost of this venture between 1984 and 2000 was around $100 billion, excluding a number of unquantifiable subsidies. If these subsidies were added, the overall spending might have doubled and the cost of wheat doubled to $1,000 per ton. The international price for wheat during that period averaged $120 a ton.

As for the cost in terms of water, between 1980 and 1999, a gargantuan volume of water—300 billion cubic meters, the equivalent to six years flow of the Nile River into Egypt—was used. Such volume translates to around 15 billion cubic meters per annum—equivalent to the volume of water that Syria and Iraq combined receives from the Euphrates River. Two-thirds of the water thus used is regarded as nonrenewable, according to estimates by the Ministry of Agriculture and Water. At this rate, it does not need to be a genius to predict that if the extraction does not stop, the non-renewable water reserves will sooner or later be depleted. The January 2008 announcement confirms this reality. ...

Food independence is impossible for a country like Saudi Arabia. ... A country like Saudi Arabia would be better off to stop desert irrigation altogether in order to spare its remaining water for drinking and household purposes for future generations.

Jan. 20, 2011 update: "Rising food prices spell trouble for Arabs" reads the United Press International headline. Excerpts:

Rising food prices, which triggered the downfall of the Tunisian regime and rioting in Algeria, threaten further trouble across the Middle East and North Africa, a region heavily dependent on food imports. The food crisis along with mushrooming populations, expanding desertification, dwindling water resources and growing unemployment create an explosive mix across the volatile region at a time when many fear new wars may soon erupt. ...

The Middle East, with an agricultural sector severely limited because of water scarcity, is particularly vulnerable to food price shocks. ... The World Bank observed in a recent report on food security in the Arab world that "Arab countries are very vulnerable to fluctuations in international commodity markets because they are heavily dependent on imported food. Arab countries are the largest importers of cereal in the world"—more than 58 million metric tons in 2007 -- "and most import at least 50 percent of the food calories they consume." It added that "of greater concern for Arab countries is that structural and cyclical forces are creating a system that is very sensitive to supply shortfalls and ever-increasing demand, making future price shocks very probable."

Feb. 10, 2011 update: Frederick Deknatel summarizes the Saudi wheat-growing effort in a book review in The Nation:

A little-known fact about Saudi Arabia: it was until recently the world's sixth-largest exporter of wheat. From 1980 to 2005, the Saudis spent some $85 billion, nearly 20 percent of the total oil revenue accumulated during the period, on subsidies for wheat farmers. In a country with a quarter of the world's known oil reserves but no natural rivers or lakes, the environmental cost of cultivating wheat was extraordinary. The Ministry of Agriculture and Water had by the 1980s built some 200 dams, seeking to trap and redirect precious, finite water from oases and ancient underground aquifers. One economist estimated that the irrigation cost for Saudi wheat farms from 1980 to 2000—more than 300 billion cubic meters of water—was "the equivalent of six years' flow of the Nile River." An American delegation to the kingdom likened "the growing of cereals at an exorbitant cost in the desert" to "planting bananas under glass in Alaska."

Apr. 4, 2016 update: In a review of the Saudi shift away from wheat, Rami Khrais finds that conditions are even worse than eight years ago:

In January 2008, the Saudi government decided to reduce its purchases of wheat from local farmers by 12.5% a year, to save water and achieve complete dependence on wheat imports to meet local needs by the year 2016. It is difficult to know whether this goal was achieved; however, it seems the government is committed to refusing wheat from local farmers. ... the policy to stop growing wheat was not well designed. Dispensing with wheat cultivation has made farmers shift to alfalfa, which consumes even more water. Perhaps it was this error that prompted the Saudi government on Dec. 7, 2015, to stop the cultivation of green feed within three years.

Dec. 1, 2016 update: One graph summarizes the whole misbegotten story of Saudi wheat.

May. 11, 2022 update: Despite the disastrous history of Saudi agriculture, some gullible observers continue to think well of it. Case in point: a Tech Space podcast ungrammatically titled "How Saudi Arabia Is Turning Their Desert Into Green Forest."

July 24, 2025 update: Asianometry has produced a podcast, "Saudi Arabia's Crazy Wheat Self-Sufficiency Policy" that offers many useful details. My favorite fact: in 1991, the Saudis pumped 50 times more water than oil out of the ground.