On founding the Middle East Forum in January 1994, I chose the slogan "Promoting American Interests" because I was struck that American participation in the just-concluded Oslo accords and other Middle East diplomacy tended not to consider U.S. interests. This same lacuna existed, to a somewhat lesser degree, also in U.S. policy toward Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, and Iran. In these cases, Washington seemed overly concerned with the welfare of those countries and not enough with the U.S. stake.

Michael Mandelbaum caught the spirit of this trend in 1996 with the derisive but accurate sobriquet "foreign policy as social work." That approach reached its awful apogee with the bizarrely named "Operation Iraqi Freedom" of 2003. I criticized this approach under George W. Bush, complaining that the Afghan and Iraqi wars "are judged more by the welfare of the defeated than by the gains to the victors."

"Promoting American Interests" serves as a corrective to this disinterested mentality.

I raise this question 17 years later because a British reader recently asked me where he fits in: "Why should I back American interests in the Middle East?" Fair question.

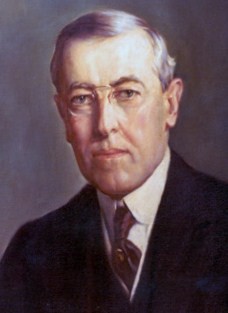

Woodrow Wilson initiated a new era in U.S. foreign policy. |

Looking at the past rival (the Soviet Union) and the future one (China) only confirm this point, but so does a comparison with the United Kingdom. London balanced hostile elements and encouraged free trade but it lacked the principled, humanitarian, idealistic approach found in U.S. foreign policy.

That's why non-Americans should also promote American interests. (January 1, 2011)

Feb. 21, 2015 update: The Middle East Forum has grown in size since I wrote the above four years ago and now includes substantial numbers of non-Americans on its roster from such countries such as Australia, Canada, Egypt, France, Germany, Israel, Lebanon, Spain, Turkey, and the United Kingdom. This has again prompted questions: Can analysts from these ten very different countries be seen as promoting American interests? Is this even a useful concept?

Yes, they can and yes, it is. An example: I served on the U.S. team working at the UN Human Rights Commission in early 1988 when our ambassador and leader was Armando Valladares, a most unusual choice.. As I wrote at the time,

He became a U.S. citizen only in January 1987 and a month later joined the U.S. delegation to the Commission. … In preparation for the 1988 meeting, President Reagan appointed Valladares head of the delegation. … [In other words,] just five years after his release from a Cuban prison, Valladares represented the United States at one of the most visible of international fora. To make this remarkable tale even more unusual, Valladares does not know the English language well enough to function in it. He therefore delivered all his public statements (speeches, press conferences, interviews) in Spanish.

I went on to mention my initial skepticism about this unusual ambassador and my conclusion that he symbolizes the American spirit:

What a remarkable country the United States is that allegiance to its principles can outweigh the natural affinities of language and culture. And what a remarkable country that someone so visibly different and so newly a citizen can represent it.

Anyone, in short, can work on the project of American interests – and all the more so at a time when the U.S. president is plausibly accused not to "love America." Discerning and promoting the country's interests is something Americans need everyone sensible to pitch in and help with, including MEF's non-American staff and fellows.