"Arab Spring" has taken off as the default description of the turbulence in the Middle East over the past 5½ months; Google shows 6.2 million mentions as opposed to 660,000 for "Arab Revolt" and a mere 57,000 for "Arab Upheaval." It's ultimately modeled on the "Prague Spring" (Pražské jaro) of 1968.

I never use this term, however, and for three reasons:

1 – It's seasonally inaccurate. The disturbances began in Tunisia on Dec. 17, 2010, at the very tail end of autumn, and the main events took place during the winter – Ben Ali's resignation on Jan. 14, Mubarak's resignation on Feb. 11, the start of the Yemeni disturbances on Jan. 15, the Syrian ones on Jan. 26, the Bahraini and Iranian ones on Feb. 14, and the Libyan ones on Feb. 15. Spring is nearly over and nothing much has happened during the past 2+ months – just more of the same. So, to be accurate, it should be called the "Arab Winter" (which gets 88,000 mentions).

2 – It implies an unwarranted optimism about the outcome. While I note the emergence of a constructive new spirit in Tahrir Square and elsewhere, and appreciate its long-term possibilities, the short-term implications have been impoverishment and thousands of deaths, with the possibility of an Islamist break-through not to be discounted.

3 – Demonstrations in Iran in 2011 have not reached anything like their 2009 proportions, but they did take place in late February and they have the potential to ignite – in which case, their importance would overwhelm anything else taking place in the region. It's a mistake to neglect Iran, where few residents speak Arabic. And keep an eye on Turkey, where the Kurds may rise up.

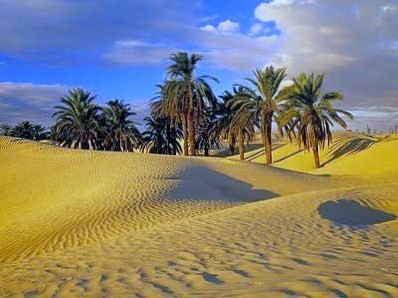

So, no "Arab Spring" for me. (And I won't even mention that this term distractedly makes me conjure up a desert oasis.) I prefer a neutral and accurate term like "Middle East upheavals" (87,000 mentions). (May 31, 2011)

An Arab spring |

Mar. 26, 2012 update: Finally, someone has joined me is protesting this silly term; Asher Susser of Tel Aviv University just published "The 'Arab Spring': The Origins of a Misnomer," where he ties the false expectations of this term to Edward Said's "orientalist" theories.