Daniel Pipes: Eleven months ago, almost to the day, a butterfly flapped its wings in a small town in Tunisia, a town of 40,000, when a policewoman slapped a fruit vendor. And so far, three despots have been overthrown, and two are on their way, the Syrian and the Yemeni. Completely unpredictable. By leave of our moderator, I'm going to skip over the roots [of the 2011 upheaval] and the way it's going and what it means for the Middle East; [instead, I will] focus on American policy.

Our policy towards these upheavals has been inconsistent, to say the least. We applauded the resignation of Hosni Mubarak in Egypt and we sat by quite complacently as the Saudis put down a rebellion in Bahrain. We used force against the despot in Libya; we have done nothing of the sort in Syria.

This inconsistency reflects more than the acknowledged amatureness, shortsightedness, and incompetence of the Obama Administration. It goes to something deeper. It goes to a conundrum that American foreign policy faces in the Middle East. As I put in an article recently, we are friendless in the Middle East. We have few allies.

And the conundrum is this: the despots, who we as Americans cannot warm to, whose regimes we would never want to live under, who impose military orders that are executed by ugly intelligence services — the despots are malleable, are without any world ambitions. They want to enjoy the good life. They want famous Hollywood actors and actresses to come celebrate their birthday parties with them. They want to keep pet tigers in their gardens. They want the finest things that Paris can offer.

They are not a threat to us. Usually — there are exceptions — but usually, they're not a threat to us. They repress millions of people to have the good life. Ugly to us, but not a threat to us.

Whereas in contrast, the democrats — the people we naturally have a feeling for — are, in fact, our very worst enemies. We just heard about Tunisia, Egypt — we will see likewise elsewhere. This has been the case since 1991 and the elections in Algeria. Wherever you look, it's the Islamists, the people who are most hostile to us, who represent a utopian ideological vision of the future, who are in line after the fascists and communists, trying to create a new man.

It is the Islamists who are popular, who have organized, who touch something that resonates in the Muslim populations, who have money, who have devoted cadres, who have years, if not decades, of experience, who are part of an international network, who have different means of accessing power — in some cases through NATO, in some cases through the ballot box — for example, in Turkey — some cases through revolution, as in Iran; some cases through military coup d'état, as in Sudan. There are many different ways to get to power. But democracy is one important way. And we find that they gain a plurality, if not a majority, in country after country. Because they are standing for something — integrity and a vision of the future.

So this is the conundrum. The people we can work with we despise. The people we admire are hostile to us. [This] makes it very difficult to have a policy. I would suggest three guidelines for policy.

First, always oppose the Islamists, plain and simple. Always. Everywhere. (Applause) Even when they come to power legitimately, as in Turkey. You may have noticed that our President hugged their prime minister just a week ago. Don't do that. (Laughter) So, that's easy. Always against the Islamists.

Two, always support those few articulate — tend to be young, modern, liberal, secular elements who are with us, who we know more clearly now than a year ago do exist. Tahrir Square is their symbol. They do exist. But they have no chance of getting to power. They do not mobilize the masses, they do not control the bayonets. Someday, possibly, they will be our partners. But not anywhere — in the near future, at least, in — except for Iran, where they might come to power. But in general, help them. Make their lives better, celebrate them, encourage them, without the expectation they'll take power.

And then finally, and most difficult, the despots themselves. We'll work with them, to improve them. They'll never be our friends. But the West as a whole, not just the United States can work on them to improve them. It's not an exciting policy, it's not an attractive policy, but it's a realistic policy. Had we spent the last 30 years nudging and pushing Mubarak, he could've ended up, in 2011, in a quite different place where he was. But we didn't. There were erratic efforts to improve the Egyptian regime, but it remained a military dictatorship, as executed by a police state. And we sat by and accepted it.

So I think in a limited way — always opposing the Islamists, always helping our friends, the liberal seculars; and in a calculated, careful, calibrated way pushing the despots in the right direction — we can have a consistent, and perhaps even successful, foreign policy in the Middle East. (Applause)

Question: Why are we inviting [to the West] the very people who have sworn to bring us down? It's, I think, perhaps naïve to think that it's not by design. There is a will somewhere to allow the undermining of the foundations of Western civilization.

Daniel Pipes: I think there is a reason — that the Left is fundamentally critical of what Western civilization is. And the more left you go, the more left, the more critical. The Islamists are critical of Western civilization. Now, they're critical from a different vantage point and for different reasons and different goals. But they are the troops for the Left these days.

Question: Is there anything the United States can do at the present time to prevent Egypt being taken over by the Muslim Brotherhood and becoming another theocracy like Iran?

Daniel Pipes: What can the U.S. do to prevent the Islamists from taking over in Egypt? Actually, I don't think we have to do a whole lot.

As I understand Egypt, there was a revolution in 1952 which overthrew a constitutional monarchy and the soldiers came in. First, Naguib till 1954, then Abdul Nasser till 1970, Sadat till 1981, Mubarak till 2011. And now, ladies and gentlemen, Mohamed Hussein Tantawi is the new ruler of Egypt. He may not call himself president — he's merely the field marshal, the chairman of the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, and the minister of defense — but he is the ruler of Egypt.

More broadly, the Egyptian military, which has ruled now for nearly 60 years, are the rulers of Egypt. They have, as I indicated before, the good life. To be a colonel in the Egyptian military is to be a very happy person. You live the good life. The Egyptian military controls a substantial part of the Egyptian economy, making everything from tissue paper to armaments. The military intends to stay in power. Even today, there was a New York Times piece about how the military intends to stay, and is maneuvering to stay in power.

The president, whoever it will be, will be not an insignificant figure, but not a determining figure. He will help figure out the budgets for the schools, and which roads need to be fixed, and other such not-unimportant tasks. But he will not be the ruler of Egypt.

The only challenge to the military are the Islamists in the army and the military. Will they succeed? Is the military proof against the Muslim Brotherhood or not? It is not like the Turkish military used to be — firmly, clearly, against Islamists in the officer core. One anecdote from Turkey: they serve liquor [in the officer mess halls]. If you don't drink your wine, you're out of the officer corps. At least, used to be the case. That's not so in Egypt. There are Islamists [in the military]. Indeed, Anwar Sadat was murdered by Islamists in the military.

I can't guarantee for you that they're going to be kept out. But that is the key. I don't think U.S. policy has too much to do with it. It's an internal, military, civil relationship. It is internal to the military. And all we can do is watch and see how well the military's keeping the Islamists from seeping into the officer corps and become the significant force within it.

Question: What would you say we need to do in the future?

Daniel Pipes: Help the Iranian opposition to overthrow the mullahs. (Applause)

Question; The thing that we've seen that's been increasingly distressing is how someone like Grover Norquist has insinuated himself deeply into the Republican Party.

Daniel Pipes: What [to do] about Grover Norquist? Well, Grover Norquist used to come to this meeting; Grover Norquist no longer comes to this meeting. Because Frank Gaffney wrote an exposé of him in FrontPage Magazine. (Applause) More broadly, I think that's symbolic that Grover Norquist's support for Islamists is not popular in conservative circles. He is an important figure. But he has had very little traction. There are only a handful of conservatives who are in agreement with Grover Norquist. And it's an anomaly, and it's not something that is taking over the Republican Party. For example, look at the Republican candidates for President. None of them, in any sense, reflect his views. I wish he'd change, I wish he would pay a price in his career for it. Certainly not coming here is paying a price for it. But I don't think it's a great danger.

Dec. 10, 2011 update: I was informed by a reader in Turkey that this page can be accessed but not the video portion of it.

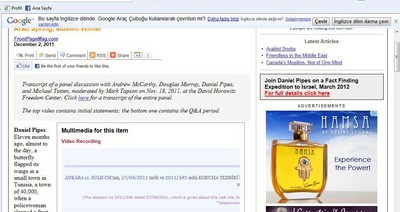

This page, as seen in Turkey. Note the missing video. |

The empty video screen reads:

ANKARA 12.SULH CM'nin 27/04/2011 tarih ve 2011/435 koruma tedbiri kapsamında bu internet sitesi (blip.tv) hakkında verdiği karar Telekomünikasyon İletişim Başkanlığınca uygulanmaktadır..

Which means in English:

In accordance with the 'protection measure' of 2011/435 dated 27/04/2011, the decision of Ankara's 12th District Criminal Court regarding this website (blip.tv) is implemented by the Directorate of Telecommunication.

Honored as I am to be banned in the AKP's Turkey, all of blip.tv appears to be censured in that country, which does take away from the thrill. This makes blip.tv one of about ten thousand websites banned in the country that also has jailed more journalists than any other.