Egypt, famed for millennia as the "breadbasket of the Mediterranean," now faces alarming food shortages. A startlingly candid report in Cairo's Al-Ahram newspaper by Gihan Shahine, entitled "Food for Stability" makes clear the extent of the crisis.

To begin, two anecdotes: Although compelled by her father to marry a cousin who could afford to house and feed her, Samar, 20, reports that they "have only had fried potatoes and aubergines for dinner most of the week." Her sisters, 10 and 13, who left school to take up work, are losing weight and suffer chronic anemia.

Manal, a nurse and single mother of four, cannot feed her children. "In the past we used to stuff cabbage with rice and eat that when we did not have any money. But now even this sometimes can be unaffordable because of rising prices. Our kids were always malnourished but it's getting even worse."

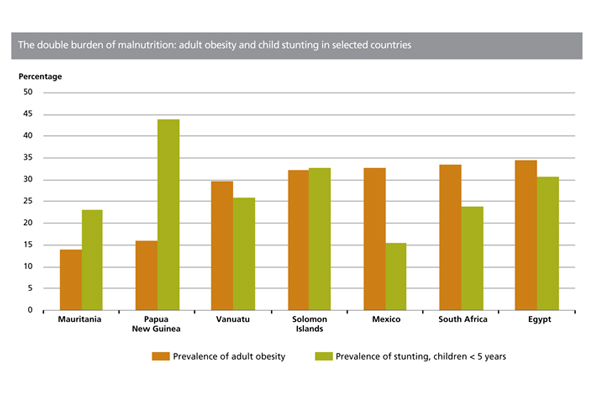

Egypt has among the worst adult obesity and child stunting rates in the world. |

These children are not unusual: according to the UN's World Food Programme (WFP), malnutrition stunts 31 percent of Egyptian children between six months and five years of age, one of the highest rates in the world. WFP also found in 2009 that malnutrition reduced Egypt's GDP by about 2 percent. One in five Egyptians faces food insecurity and "a growing number of people can't afford to purchase enough nutritious food," according to Australia's Future Directions International (FDI). To fill their stomachs, Egypt's poor rely on low-nutrition, calorie-dense foods (such as the infamous all-starch kushari) that cause both nutritional deficiencies and obesity. And 5.2 percent of the population is actually going hungry, an Egyptian state agency, CAPMAS, reports.

Many factors contribute to Egypt's hunger crisis. Going from the deepest to the most superficial, these include:

Flawed government policies: Cairo has consistently favored urban over rural areas, leading to reduced agricultural research, a lack of financial support, private sector monopolies, cock-eyed subsidies, smuggling, corruption, and black markets. Farmers suffer from shortages of expensive yet inferior seeds, fertilizers and pesticides. But most pernicious of all has been the reduction in cultivated land because of the government's complicity in unconstrained and illegal residential sprawl.

Reliance on food imports: Historically self-sufficient, Egypt now – according to FDI – imports 60 percent of its food. The country remains largely self-sufficient in fruit and vegetables but depends heavily on foreign grains, sugar, meat, and edible oils. Egypt imports 2/3 of its wheat (10 million tons of a total of 15 million, making it the world's largest importer of wheat), 70 percent of its beans, and 99 percent of its lentils. Not coincidentally, lentil cultivation has dropped from 85,000 acres to below 1,000 acres. Largesse from friendly oil-exporting states of about US$20 billion in 2013 has been crucial to fund food imports but one must wonder for how long this subsidy will continue.

Kushari stands offer meals made up of various starches, such as pasta, potato, and rice with a sauce on top. |

Poverty: Such dependence on fluctuating international markets is ever more risky as Egypt becomes increasingly destitute. The previous average of 6.2 percent real GDP growth fell to 2.1 percent in 2012-13, WFP reports. Unemployment stands at about 19 percent. The cotton harvest, once the pride of Egypt, saw a production decline of more than 11 percent in a single marketing year, 2012 to 2013. Twenty-eight percent of young people live in poverty and 24 percent live just above the poverty line, CAPMAS reports, an increase of 1 percent in a single year.

Water scarcity: The gift of the Nile is already insufficient by 20 billion cubic meters annually because of such factors as a growing population and inefficient irrigation, reducing Egypt's food production; and with new dams under construction on the Blue Nile in Ethiopia, yet more severe shortages will follow within the decade.

Recent crises: FDI notes "the avian influenza epidemic in 2006, the food, fuel and financial crises of 2007-09, the 2010 global food price spike, and the economic deterioration caused by political instability since the 2011 Revolution."

Can the new government of Abdel-Fattah el-Sisi respond in time to reverse these calamitous trends? I am pessimistic. Millions of volatile Cairenes have far greater political clout than the more numerous fellahin quietly tending their fields. Moreover, urgent issues – from discontented factory workers to a Muslim Brotherhood rebellion to a Hamas-Israel ceasefire – invariably distract the leadership's attention from long-term systemic crises such as food production.

The interests of Egyptian farmers (fellahin), rank low on the government's list of priorities. |

Starvation in Egypt is yet another of the Middle East's many deep, endemic problems, problems which outsiders cannot solve, only protect themselves from.

Mr. Pipes (DanielPipes.org) is president of the Middle East Forum. © 2014 by Daniel Pipes. All rights reserved.

Oct. 6, 2014 addendum: I cover a complementary topic at "Fixing Egypt's Economy: No More Military Macaroni."

Dec. 12, 2014 update: Wheat figures for the fiscal year July 2013 to June 2014 finds that Egyptians imported 5.46 million tons of the staple, or 60 percent of the total consumption, making them the world's largest importers of the grain.

Mar. 12, 2015 update: In an interview with Lally Weymouth of the Washington Post, Egypt's President Sisi worries even more starkly about his country's future than do I. A few excerpts:

LW: There are countries that are suffering from disintegration and security collapse. ... How can I protect my country?

Sisi: You [Americans] look at Egypt with American eyes. Democracy in your country has evolved over 200 years. Just give us a chance to develop. If we rush things, countries like ours will collapse.

To which, Weymouth replies and they have an exchange:

LW: You've said the word "collapse" twice now. Is that something that concerns you?

Sisi: Of course.

LW: Nobody else mentions it.

Sisi: You know why? Because they have a lot of confidence in Sisi. But I am just a human being. I cannot do everything. When Somalia collapsed, didn't the U.S. leave? Do you want Egypt to become a failed state and then you wash your hands of it?

The interview concludes on this note:

LW: What do you worry about?

Sisi: That my country will collapse. That is the only thing. Honestly, I don't think about my own life for a second.

Comment: Sisi is entirely justified in his worry about a collapse.

June 6, 2015 update: Egypt is annually losing 12,600 acres or 51 square km. of agricultural land to urban development. According to the World Bank, the country has 36,120,000 square km. under cultivation. At this rate, it will be a while before the pinch is felt.

Oct. 1, 2015 update: Mona El-Fiqi of Egypt's Al-Ahram looks at the problems plaguing the country's cotton crop and finds much to worry about:

It seems that international and local markets are no longer interested in purchasing Egyptian long staple cotton due to its high price compared to cheaper short and medium staple varieties.

Locally cultivated cotton is also plagued by low productivity, due to a lack of investment in research on improving the cotton crop. ... Egyptian cotton has suffered from a series of problems starting from a lack of high-quality seeds, spiralling cultivation costs, and the lack of a comprehensive marketing policy. The result has been a decline in cultivated land from three million feddans in the 1980s to 300,000 feddans today.

Oct. 14, 2015 update: I am in Gainesville, Florida, and was hungry on the road. Looking for a quick bite, I did a double take on seeing a restaurant called "Cairo Grille" – the first time I'd ever seen an Egyptian restaurant outside of Egypt. It turned out to be inexpensive and tasty. I was particularly struck by the presence on the menu of kushari, spelled the French way, composed of "lentil beans, rice and pasta in a tomato sauce topped with fried onions." (In Egypt, it's usually made up of potatoes, not lentil beans.)

Kushari on the menu in Florida. |

Feb. 18, 2016 update: I look at declining Nile waters today at "Can Egypt and Ethiopia Share the Nile?"

May 29, 2016 update: Albaraa Abdullah recounts a story of official incompetence and perhaps corruption in "Is Egyptian government pushing farmers to stop growing wheat?" As though the country's farmers need yet another obstacle to growing and selling their product.

June 17, 2016 update: With drought afflicting the Horn of Africa and the Nile flow less generous than normally, a crackdown on water-hogging crops has reached the point that government representatives are spraying incendiary compounds on rice crops planted in violation of a prohibition on rice cultivation. Bananas and sugarcane are also being limited.

Oct. 24, 2016 update: A sign of the sugar crisis: Edita, the largest food company in Egypt's Stock Exchange, halted production when government authorities seized the company's 2,000 tons of sugar due to a national shortage of sugar caused by an acute decline in hard currency.

Oct. 24, 2016 update: A sign of the sugar crisis: Edita, the largest food company in Egypt's Stock Exchange, halted production when government authorities seized the company's 2,000 tons of sugar due to a national shortage of sugar caused by an acute decline in hard currency.

Nov. 24, 2016 update: Nader Noureddin, professor of soil and water sciences at Cairo University's Faculty of Agriculture, writes in "Egypt's Food Needs" about efforts to address Egypt's growing food shortage. Some highlights:

Egypt is suffering from an acute food deficit, estimated at around 60 per cent of its strategic food needs. It is barely self-sufficient in fruit, vegetables, potatoes and eggs, and it has to import 70 per cent of its needs in wheat and fava beans, 32 per cent of its sugar needs, all its food oil, lentils and yellow corn feed needs, and 60 per cent of its needs of red meat, butter and powdered milk.

Egypt has topped the list of the world's major wheat importers since 2005. This year it imported 12 million tons of wheat. It is the fourth largest yellow corn feed importer, at eight million tons annually, and the seventh largest food oil importer, at the rate of three million tons per year.

A large portion of this food gap is connected with Egypt's shortage of water resources and the agricultural land needed to expand food production. With only 62 billion m3 per year of fresh water resources, Egypt is classified among the countries suffering from "water scarcity". The per capita share of these resources has fallen below the minimal level of water needs, estimated at 1,000 m3 per year, to 680 m3. Due to this paucity of water, hopes are now pinned on vertical development, or increasing the production of units of cultivable land and increasing the returns from such units by intensifying the search for new subterranean water resources for irrigation purposes.

The Sisi government has passed legislation encouraging investment:

Under the recently passed investment law, investors in the agricultural sector who cultivate or "grow and process" the strategic foodstuffs that are currently imported in large quantities will be exempted from taxes for five years and entitled to a 50 per cent tax exemption thereafter. The purpose is to stimulate the cultivation of food oil plants (such as sunflowers), soya beans, corn feed, lentils, fava beans, beetroot, sugarcane and wheat and/or expansion in the construction of livestock feedlots.

More generally, lawmakers hope to encourage investment in the agricultural sector, normally not as attractive to investors as other sectors.

The government's effort "to keep food prices low and within reach of the wallets of poor and limited-income sectors of society so as to ward off social unrest and instability" accounts for this low return. It has a perverse consequence:

Specialists in this field warn of the risks of what they term "hidden hunger" or "the new face of hunger," by which they mean the phenomenon of supermarket shelves brimming with food but at prices that are beyond the capacities of the poor or even broader sectors of consumers, effectively rendering those things unavailable.

That said,

The government's recent economic decisions, especially the decision to float the Egyptian pound, should give a boost to the agricultural sector and offer unprecedented incentives to Egyptian and foreign farmers and investors to increase their cultivation of strategic crops. Now that the price of importing their equivalents in dollars has nearly doubled in terms of the Egyptian pound, growing and processing these crops domestically will be far more profitable than before.

Surveying various crops, Noureddin confidently predicts that

the Egyptian agricultural sector will be one of those benefitting most from the recent economic decisions, and especially from the floating of the pound leading to a higher exchange rate for the dollar. The measures will help stimulate an Egyptian agricultural revival. Egypt's farmers will reintroduce crops they had stopped cultivating due to poor economic returns. And the new exchange rate will give a powerful boost to Egyptian fruit and vegetable exports to other countries in the Arab world and to EU countries, Russia, Ukraine and Japan.

He concludes that

We can look forward to a period in which Egyptian vegetables will return with vigour to European markets after the long hiatus since July 2010.

Mar. 28, 2019 update: Mohamed Abdel-Aati, Egypt's minister of water resources and irrigation, estimates that an Egyptian's per-capita annual share of water has decreased 90 percent in the past 1½ centuries, from 6,000 cubic meters per capita in 1870 to 600 cubic meters today.