In a typical assessment of recent European elections, Katy O'Donnell writes in Politico that "Nationalist parties now have a toehold everywhere from Italy to Finland, raising fears the continent is backpedaling toward the kinds of policies that led to catastrophe in the first half of the 20th century." Many Jews, like Menachem Margolin, head of the European Jewish Association, echo her fear, seeing "a very real threat from populist movements across Europe."

Of all countries, Austria and Germany naturally arouse the most concern, being the homelands of Nazism. The surging success of the Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ) and the Alternative for Germany (AfD), with 26 and 13 percent of the vote, respectively, has made them both important political actors and horrified observers. Thus does Germany's foreign minister, Sigmar Gabriel, call the AfD "real Nazis." "A nightmare come true," says Charlotte Knobloch, the former president of Germany's Central Council of Jews.

Are they correct that we are slouching back to the 1930s? Or, to the contrary, might this insurgency indicate a healthy means for Europeans to protect their mores and culture? I shall argue the latter.

To begin with, these parties are not nationalist as of old, boasting neither of British imperial power nor German bloodlines. Rather, they have a European and Western outlook; to coin a term, they are civilizationist. Second, they are defensive, focused on protecting Western civilization rather than on destroying it as Communists and Nazis dreamed to do, or on extending it, as the French government long attempted. They seek not conquests but to retain the Europe of Athens, Florence, and Amsterdam. Third, these parties cannot be called far-right, for they offer a complex mix of right (culture) and left (economics). Marine le Pen's National Front, for example, calls for French banks to be nationalized and attracts leftist support.

A civilizationist AfD election poster: "Burkas? We like bikinis." |

Rather, these parties are anti-immigration. A massive and sometimes uncontrolled immigration of non-Westerners, causing a sense of feeling like strangers in one's own home, fuels their appeal. Pathetic stories of pensioners surrounded by foreigners and scared to leave their apartments ricochet around Europe, as do tales of a single indigenous student in a school otherwise entirely made up of immigrant children. The parties all aspire to control, diminish, and even undo the immigration of recent decades, and especially of Muslims.

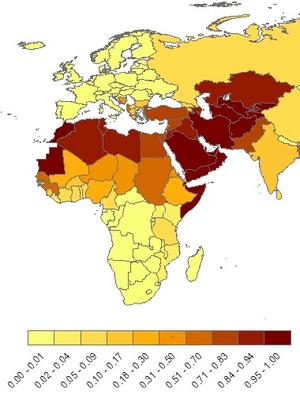

Note how Europe is almost surrounded by Muslim-majority countries. |

Two more factors complete the civilizational anxiety: the catastrophically low birth rate of Europeans (average number of children per woman: 1.6) and an elite (what I call the six Ps: police, politicians, press, priests, professors, and prosecutors) that ignores and even denigrates those concerns. When a voter expressed anxiety in September 2015 to Angela Merkel about uncontrolled migration, the German chancellor humiliated her with a scolding about Europe's deficiencies and admonishing her to go to church more often.

Together, these developments led to the proliferation and rise of anti-immigration parties through much of Europe. From the venerable National Front in France (founded 1972) to the AfD (founded 2013), they fill a profound need. From virtually no presence twenty years ago, they have rapidly become an important, if marginalized, force in twenty European countries. In the words of Geert Wilders, leader of the Dutch anti-immigration PVV party, "In the Eastern part of Europe, anti-Islamification and anti-mass migration parties see a surge in popular support. Resistance is growing in the West, as well."

That said, almost without exception, they suffer from deep problems. Mainly staffed by novices, they contain dismaying proportions of power-hungry eccentrics, conspiracy theorists, historical revisionists, and anti-Jewish or anti-Muslim extremists. These shortcomings translate into electoral weakness: if polls in Germany show about 60 percent of the voting public worried about Islam and Muslims, only one-fifth as many vote AfD. This implies that, once anti-immigration parties convince the voters they can be trusted with power, they can grow very substantially, perhaps even winning majorities. But that's a long way off.

Sebastian Kurz (L, ÖVP) and Heinz-Christian Strache (FPÖ) have much to discuss. |

So, rather than attempt in vain to ostracize anti-immigration parties that are not dangerous and that will grow far beyond their current strength, the six Ps should encourage the leaders to slough off radical elements, gain experience, and otherwise prepare themselves for governance. Like them or despise them, these parties inevitably will have some part of a mandate to deal very differently with immigration – and much else.

Mr. Pipes (DanielPipes.org, @DanielPipes) is president of the Middle East Forum. © 2017 by Daniel Pipes. All rights reserved.

Washington Times graphic for this article. |

Dec. 10, 2017 update: A reader, Robert Blumenblatt, points out to me that Rogers Brubaker, "Between nationalism and civilizationism: the European populist moment in comparative perspective," Ethnic and Racial Studies, 40 (2017): 1191-1226, uses the term civilizationism in a way that anticipates my own.

Dec. 17, 2017 update: Gábor Vona, chairman of Hungary's overtly antisemitic Jobbik party, has renounced this legacy and declared a permanent change: "The kind of anti-Semitic expressions which took place in Jobbik earlier are impossible to imagine. Or if they did, they would naturally draw the most severe sanctions. The process of becoming a people's party is not a political tactic ... but a process experienced internally. So there is no way back from here."

Comment: Is Golden Dawn next?