May I, an American citizen living in the United States, comment publicly on Israeli decision making?

Yoram Schweitzer wants me not to judge decisions made by the Israeli government. |

Schweitzer does not spell out the logic behind his resentment, but it rings familiar: Unless a person lives in Israel, the argument goes, pays its taxes, puts himself at risk in its streets, and has children in its armed forces, he should not second-guess Israeli decisionmaking. This approach, broadly speaking, stands behind the positions taken by the American Israel Public Affairs Committee and other prominent Jewish institutions.

I respect that position without accepting its discipline. Responding to what foreign governments do is my meat and potatoes as a U.S. foreign policy analyst who spent time in the State and Defense departments and as a board member of the U.S. Institute of Peace, and who as a columnist has for nearly a decade unburdened himself of opinions. A quick bibliographic review finds me judging many governments, including the British, Canadian, Danish, French, German, Iranian, Nepalese, Saudi, South Korean, Syrian, and Turkish.

Obviously, I do not have children serving in the armed forces of all these countries, but I assess their developments to help guide my readers' thinking. No one from these others countries, it bears noting, ever asked me to withhold comment on their internal affairs. And Schweitzer himself proffers advice to others; in July 2005, for example, he instructed Muslim leaders in Europe to be "more forceful in their rejection of the radical Islamic element." Independent analysts all do this.

So, Schweitzer and I may comment on developments around the world, but, when it comes to Israel, my mind should empty of thoughts, my tongue fall silent, and my keyboard go still? Hardly.

On a more profound level, I protest the whole concept of privileged information – that one's location, age, ethnicity, academic degrees, experience, or some other quality validates one's views. The recent book by Christopher Cerf and Victor S. Navasky titled I Wish I Hadn't Said that: The Experts Speak - and Get it Wrong! humorously memorializes and exposes this conceit. Living in a country does not necessarily make one wiser about it.

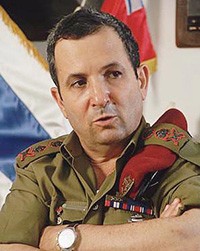

Ehud Barak, the most highly decorated soldier in Israeli history, made mistakes. |

It is a mistake to reject information, ideas, or analysis on the basis of credentials. Correct and important thoughts can come from any provenance – even from thousands of miles away.

In that spirit, here are two responses concerning Schweitzer's take on the Samir al-Kuntar incident. Schweitzer argues that "to fail to do the utmost to rescue any citizen or soldier who falls into enemy hands would shatter one of the basic precepts of Israeli society." I agree that rescuing soldiers or their remains is an operationally useful and morally noble priority, but "utmost" has its limits. For example, a government should not hand over live terrorists in return for soldiers' corpses. In like manner, the Olmert government's actions last week went much too far.

Another specific: Schweitzer claims that, "relatively speaking, the recent exchange with Hizbullah came at a cheap price. It is debatable whether Kuntar's release granted any kind of moral victory to Hizbullah." If that deal was cheap, I dread to imagine how an expensive one would look. And with Kuntar's arrival in Lebanon shutting down the government in giddy national celebration, denying Hizbullah a victory amounts to willful blindness.

July 28, 2008 addenda: (1) Over a decade ago, I replied a first time to the challenge quoted above, at "Who Are You to Criticize Ehud Barak?"

(2) In addition to the comments below, I commend the roughly 100 "talkback" comments at the Jerusalem Post site. They are distinctly friendly to my argument - considerably more so than I would have expected.

Also, this may the right place to record a statement made by Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin weeks before his death (as reported in the Jerusalem Post, September 24, 1995), when he memorably addressed American Jews and told them that they

have no right to patronize Israel. They have no right to intervene in the way the people of Israel have decided, in a very democratic way, on which direction to go when it comes to war and peace. They have the right to speak to us, but by no means to act, as Americans, against the policy of the government of Israel. . . . Whoever does not have daughters or sons who serve in the [Israeli] army has no right to intervene or act on issues of war and peace.

Comment: Paradoxical, no, that an Israeli tells Americans they have no right to tell Israelis what to do - even as he tells Americans what to do? This relationship gets very complex, very fast.

Aug. 3, 2008 update: Schweitzer has again critiqued me, to which I have commented at "A Final Reply to Yoram Schweitzer."

Sep. 29, 2013 update: Schweitzer finds that I disagree too much with the Government of Israel but David Speedie finds that I agree too much with it. For my response to Speedie see "Do I Not Criticize Israeli Policies?" The common theme in my responses to both of them is simple: I am an independent analyst who calls 'em as he sees 'em.