The sometimes deep involvement of Arabic-speaking Muslims in selling alcohol in the United States stands out as one of the most surprising patterns of American Islam.

In an anthropological study, The Arab Moslems in the United States: Religion and Assimilation (New Haven, Conn.: College & University Press, 1966), Abdo A. Elkholy presents field research he did in 1959 in two Muslim communities, Toledo, Ohio and Detroit. The book contains a very precious glimpse of Islam in the United States just before the immigration law was overhauled in 1965, leading to a permanent change in the nature of American Islam. He found that Muslims were attracted to Toledo

by the liquor business which one Moslem family was said to have entered. This family imported relatives from other [American] states and employed them to meet the business expansion, securing maximum profit with minimum cost in paying wages. But those business-minded relatives very quickly realized the attractive net profits, and thus branched out in the same business direction, helped by the first family. The relatives brought others with them to start the same cycle; the news was spread, and in less than twenty years the Moslems owned 127 of the city's 420 bars, or about 30 per cent, in addition to liquor stores, carry-out businesses, and restaurants with liquor licenses. Some Moslems today have two or three bars. Many retire but keep the bars, either running them through hired workers or subletting them with the reservation of license ownership. Some with high status occupations also indulge in bar ownership, hire help, and invest their outside working hours in the business.

"The Arab Moslems in the United States: Religion and Assimilation" by Abdo A. Elkholy.

It has become well known in and around Toledo that the city's liquor business is almost monopolized by the Moslems who had actually started this trend by chance, and continued it by profit-orientation, cohesive relationships, and natural jealousy among the relatives to imitate the successful members. The cost of a liquor license has risen in the last ten years from $600 to $20,000 and more on the black market. One of the interviewees said: "Liquor is the most profitable business we have ever experienced. You never lose on it or bear any waste by contamination. To give you just one example, last year I sold in my restaurant whiskey for $11,000. The net profit was $9,000." (p. 18)

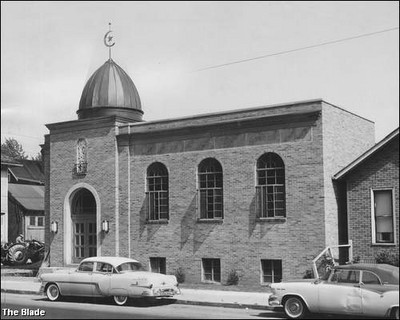

At one time in Toledo, he relates, more than half of Muslim males owned a bar or restaurant; and a community that amounted to just one third of 1 percent of the city's population owned over 30 percent of its bars. That city's handsome mosque, in other words, may be the only one in the world built primarily from the profits of liquor sales.

Toldeo, Ohio's first mosque - and the only one in the world largely financed by liquor sales? |

Elkholy draws two conclusions from Toledo's occupational pattern:

First, assimilation itself leads to the possibility of certain occupational patterns. Toledo Moslems would not have dared to choose the traditionally condemned liquor business had they not assimilated the new values and adjusted themselves to the American culture. This leads to the second significant point: selectivity. The members who came to Toledo were selective groups from among the Arab Moslems who were scattered all over the United States. Selectivity here means that the liquor business attracted to Toledo a special class of Moslems - those fifty years later, characterized by readiness to sacrifice some traditional values. (p. 140)

Dalal Food & Liquor in Chicago's Loop. |

Despite the many changes in American Islam over the past nearly forty years, this pattern of disproportionate Muslim involvement in selling liquor and other haram items still persists, This weblog entry pursues that topic.

Mar. 18, 2003 update: According to Mohamed Saleh Mohamed, president of the Yemeni American Grocers Association, immigrants from Yemen own 4/5s of the 360 markets that sell alcohol in Oakland.

Nov. 26, 2005 update: A gang of about a dozen pipe-and club-wielding African-American men in suits and bow ties attacked two liquor stores in West Oakland, California, the New York Market and San Pablo Market and Liquor, on Nov. 23 just before midnight. In the course of their rampage, they smashed cooler doors and liquor bottles, overthrew shelves of food, and did at least $30,000 in damages. Also, according to Oakland's Deputy Police Chief Howard Jordan, "In both incidents, the suspects entered the store and questioned why a Muslim-owned store would sell alcoholic beverages when it is against the Muslim religion."

The 17-year-old son of the owner of San Pablo Market and Liquor, Kaled Saleh, recounted what happened: "They asked us if we were Muslim. When we said 'yes,' one of them said that good Muslims shouldn't be poisoning the community with alcohol, or something like that."

Surveillance tape caught the attack on San Pablo Liquor, enabling police to identify about half of the vandals who are likely members of an Oakland off-shoot of the Nation of Islam, a group bearing the innocuous name of Your Black Muslim Bakery. Members of this group, who wear trademark suits and bow ties, attacked a liquor store at least once before, in North Richmond in January 1993.

Nov. 27, 2005 update: In response to the attacks, Mohamad Saleh Mohamad, president of the Yemini American Grocery Association, which represents about 300 store owners in Oakland, Berkeley and Richmond, denounced the attack as "a criminal act" and added: "It had nothing to do with religion, In this country we have the right to do business. We are selling legal products."

The story in the Alameda Times-Star also adds that a new Yemeni-owned store on in Richmond "was attacked by men in a fashion exactly like the attacks on the two Oakland stores last week." It quotes the owner: "They told me not to sell alcohol or they would be back. They didn't come back." The account continues: "the attack ruined his business and he closed the store. His new store does not sell alcohol."

Nov. 28, 2005 update: A fire broke out after midnight at the New York Market, doing major structural damage to the building.

Nov. 29, 2005 update: Abdel Hamdan, a clerk at the New York Market, was abducted for half a day and eventually found alive in the trunk of a car.

Yusef Bey IV, 19, the son of the founder of Your Black Muslim Bakery, and Donald Cunningham, 73, a man with long-time links to his father, turned themselves in to the police and face charges that include robbery, felony vandalism, and terrorist threats.

Dec. 1, 2005 update: Bey and Cunningham were arraigned and assigned bail of $170,000 and $110,000 bail, respectively.

Dec. 8, 2005 update: The police arrested two more suspects in the vandalism case, Kahlil Raheem and Dyamen Williams.

Dec. 9, 2005 update: Moe Saleh (presumably Muhammad Saleh), the owner of New York Market, spoke out about himself and his store:

I did not open a store because I had no other options. I genuinely love people and the business I am in. ...

Yes, we sold alcoholic beverages but we did not have hard liquor, just beer and wine. Out of the 16 cooler doors that we had in the store, I believe that four or five were used for alcoholic beverages—so you couldn't say we were just another liquor store. We had a meat department a full line of groceries and a small produce section. It was a market. It was definitely not a liquor store.

Dec. 12, 2005 update: Cecily Burt of the Oakland Tribune apprises the situation in an article, "Selling liquor creates religious conflict for Muslims: Oakland store owners torn over promoting product their faith shuns." She tells the story of Amin Nagi, who sold liquor for 20 years and long tried to reconcile his faith with his business.

In the end, the internal struggle and family pressure proved too much. Nagi sold the store this year and opened a bright, airy Super Discount mart in Oakland's Fruitvale district. He sells loads of stuff — baseball caps, helium balloons, luggage, clothes, watches. Noticeably absent: liquor. He is finally at peace with his beliefs, which forbid association with alcohol.

In Nagi's own words:

"When I prayed, I would say 'What am I doing?' I had a dream to get out, and I'm very happy," he said. "It bothered my wife and my father. He was totally against me. He would say, 'I raise you with halal, the right things. I worked for you, you shouldn't do this.' It wasn't easy. My kids said, 'Hey, we don't want you in this business no more, get out.' Me too, I always felt guilty. I pray to Allah for forgiveness because it's not a good thing; not a good product to sell."

Mohamed Saleh Mohamed, president of the Yemeni-American Grocers Association, also feels the pressure:

Our religion does not allow us to sell alcohol, but we have many excuses to do it. This is the worst business; this is wrong, the worst thing I could ever think about. But we're caught in a Catch-22. I'm not saying what we do is right, but it's within the system.

Mohamed explains the roots of the paradox: "America is full of opportunity, but most of the store owners come from Yemen and they are not educated, so this is the best they can do."

The president of the Islamic Society of San Francisco, Souleiman Ghali, agrees about the lack of opportunity:

For us, it's very disturbing and very unfortunate, and it's something we try to speak about in sermons and at our mosques. Even [for] those who sell [liquor], it is something deep down they hate. They don't like selling it, but they don't know any other means to make a living.

Many of them try their best to get out of it any way they can grab, and we've seen some of them sell their business and lose money. We don't feel that anyone selling alcohol thinks they are doing the right thing. They regret it deep, deep inside.

Burt finds the origins of Muslim-owned liquor stores not going back far:

No one knows for sure exactly when the Yemeni community cornered the market on liquor stores. Mohamed said it started at least 15 years ago. Before that, the small corner stores were owned by blacks and Asians, and before that, the Italians, Greeks and Slavs. It has always been an immigrant way of life, a way to achieve the American dream.

Mohamed notes that Yemeni store owners are eager to leave the liquor business, internal conflicts notwithstanding.

Feb. 6, 2007 update: Pauline Bartolone of National Public Radio gets her report from West Oakland, California off to a bad start by euphemistically stating that the two liquor stores vandalized in 2005 were wrecked by "a crowd of men." No description, no adjectives.

Bartolone then tells the story of Soliah Agabri, the Yemeni Muslim owner since 2000 of Neighbor's Market in West Oakland , a successful liquor store, and how he plans to get out of the business: " I'm trying to get out of the alcohol. That's what I'm trying to do. I don't really want to sell anymore." He currently earns $200-$300 a day, "an amount he's confident can be replaced by serving hot food. So that's just what he's doing. He redesigned his market to be alcohol free. The beer refrigerators will soon become part of the deli where locals can grab hotdogs or a bowl of soup. He unrolls his sketch of the new design and smiles widely."

All of the nearly $35,000 the changeover is coming from the Environmental Justice Institute, an Oakland nonprofit working to convert liquor stores into food markets. Other liquor store owners are watching to see if this switch works.

Zaid Shakir, a local imam, is also pressing to get Muslims out of the business. Bartolone quotes him making the interesting assertion that "when you come and sell [alcohol] in the community, it's no longer a private affair. You're in ... violation of the law. The law of this land is affecting the lives of others. And that's what we're against."

Comments: (1) No one can object to fewer liquor stores in poor neighborhoods, but it is intolerable that they should leave their legitimate business under the gun of being pillaged. (2) Note NPR's protecting NoI. (3) Shakir seems to confuse two laws, Islamic and U.S. Someone needs to tell him that the Constitution, and not yet the Koran, still rules in West Oakland.

Jan. 15, 2008 update: At a preliminary hearing for the four alleged vandals, the defense attorney for Raheem responded to the hate crime charge by stating that "The only thing hated in this case is liquor. Just because a group of Muslims were upset that some people were selling liquor and those people happen to be Muslim, does that mean they hate Muslims? Of course not."

June 20, 2010 update: Manya A. Brachear reports in the Chicago Tribune about the situation in the Chicago area:

Prescribed by his Islamic faith to pray five times a day, Mazen Materieh often prostrates himself on one of the prayer rugs in the basement of his corner store. When he is done, he returns to his perch behind the counter, where he sells liquor, lottery tickets and pork skins — all forbidden by the Quran and the Prophet Muhammad. "I'm not justifying what I'm doing. I know it's wrong," said Materieh, 52, of Orland Park. "I'm an honest person. I don't like to be a man of two faces."

Materieh's conflict is common in corner stores across Chicago's South Side. On one hand, store owners cannot make ends meet without selling what customers demand. On the other, consuming or profiting from products forbidden by their faith is considered sinful. What's more, neighbors blame the stores for perpetuating violence, addiction and obesity in low-income neighborhoods.

According to one report , Muslims own some 3,000 liquor stores in just the Chicago area.

Comment: This microcosm of the Muslim experience in the United States symbolizes the vast and fascinating changes Islam undergoes in a radically new environment, one most basically characterized by the state leaving people be religiously.

July 23, 2010 update: Maytha Alhassen, a Ph.D. student at the University of Southern California, did some on-site research for a report, "The Liquor Store Wars: Interracial Tensions and Muslim Image-Making in the 'Hood'." Among her more interesting quotes is one from Zaid Shakir, an imam (also quoted above): "In Yemen, you had zero economic options. It was just be poor and die. That was it. You come to America; there are a thousand things you can do to make money lawfully." Hmm, and to think that some imagine liquor to be a legal trade in the United States.

Aug. 17, 2010 update: Unsa Suhail reports in the Muslim-American magazine Illume that "Muslims Get Grant For Liquor Stores To Become Grocery Stores." Specifically,

The Council of Islamic Organizations of Greater Chicago has put a grant in place for African-American and Arab Muslims in order to encourage Muslims to stop selling liquor. The Inner City Muslim Action Network has set up a loan program to help fund and provide these guilt-ridden owners with fresh produce and other healthy goods by supporting the bill of Illinois Fresh Food Fund. This bill would serve neighborhoods where grocery outlets are scarce. In turn, the store owners would be surrounded by better company. Executive director of the Inner City Muslim Action Network, Rami Nashashibi said in a World Wide Religious News Report, "These stores became associated with a lot of the most negative and oppressive characteristics you would want to be associated with."

Suhail also provides background information on this pattern, focusing on the Bay Area. According to Ed Kikumoto, a community activist, members of the Yemeni-American Grocers Association own more than 80 percent of the 300 liquor stores in Oakland; Zachary Twist, coordinator of Muslims for Healthy Communities, estimates that "over 90 percent of Oakland's 350 liquor stores are owned or operated by Muslims." Suhail interviews Saeed Azimzadeh, 63, an aspiring Yemeni engineer who ended up depending on liquor sales:

The gold plated "Allah" sign hangs in Saeed Azimzadeh's store right next to his license to sell liquor in the San Francisco Bay Area. Born and raised in Yemen, Azimzadeh earned a degree in Civil Engineering. When he had the opportunity to come to America, he dreamed of putting his skills to use in a non-oppressive country where his wife and two children could thrive. After five years of getting turned down and rejected by each place he applied, Azimzadeh gave up, and turned to liquor. ...

Azimzadeh opened up his store in 1996. He saw a "for lease" sign when he was on his way home and decided to take on a business adventure. "It was a halal meat store at first, but I made nothing. I couldn't live comfortably. Each expense brought more stress. A friend of mine encouraged me to turn it into a late night market store, [and when] we stocked the shelves with alcohol, the money started coming in." Azimzadeh twisted his wedding ring from side to side "I don't think Allah wants anyone to suffer, and I was suffering, my family was suffering. I couldn't live that way" ...

He is not exactly proud of his trade but he does insist on it:

Although advertising alcoholic merchandise is undeniably against Islamic law, Azimzadeh insists that providing for his family is the main goal. "There are very few Muslims in this community [so] selling halal things do not make a profit. The money to start the store will help, but that is not money that will keep coming in." He continued, "Profit comes from customers. I have to pay for my family and my sick wife. Selling liquor is the only way I can do that. ... Am I proud of this store? No. But paying bills doesn't cover religious restrictions. It is money they want and that is what I have to give them."

Azimzadeh points to the need to sell alcohol:

Only liquor sells in this neighborhood. I can't sell groceries and compete with the other stores. I can sell discount liquor. And I will be judged when that day [of Judgment] comes. No one else can impose their opinions on me. My kids are in college, my wife needs medical help, and sadly, selling liquor keeps everything together. ... I do not like that I sell liquor, but it in this area it is the only thing people want. Competing with these grocery stores is impossible. ... I am not a rich man. I don't have a luxury car or a big home. I just make enough to get by. And if I don't have this business, I don't have anything.

July 23, 2014 update: To my surprise, a woman in hijab served me a martini today in Philadelphia.

May 21, 2018 update: Today I was served by a hijabi in a Philadelphia liquor store.

June 14, 2018 update: Today, served by a hijabi in a Claymont, Delaware, liquor store.

Oct. 1, 2018 update: Katherine Poppe argues in a study of Nidal Hasan, the Ft. Hood jihadi who in 2009 killed 13 fellows soldiers and wounded 31, that he was motivated in large part by his mother selling liquor:

Hasan's parents owned a convenience store that sold alcohol, which Hasan came to believe as forbidden by Islam. The sin of selling alcohol would, in Hasan's mind, damn his mother to an eternity of burning in hell. This religious interpretation was one he believed to be entirely literal—his mother would spend an eternity burning in a pit of fire. Hasan felt that there was a way for him to help his mother and prevent her from suffering this terrible fate. Her sins, as he saw them, could be outweighed by good actions he did on her behalf. Thus, good deeds and actions as a devout, pious Muslim could gain him a sort of "religious karma" that could be spent on erasing his mother's earthly sins. ...

After the death of his mother, Hasan was emotionally devastated and terrified of the eternal suffering he believed she would suffer for her perceived sins. In his "Koranic Worldview," Hasan describes in detail what he believed were the very real tortures of hell. He writes: "If you do not submit [to God] and God condemns you to hell, there is much to fear." He then lists several verses of the Qur'an describing sinners being boiled alive, burning in hellfire, and being unable to escape the torment. The fear of his mother's perceived condemnation drove Hasan to seek out religious solutions, further priming him for the path to radicalization. ...

Hasan also wrote that he believed a person could intercede on behalf of others regarding their rank. In particular, he thought that his good deeds could be used to help improve the position of his mother, who he feared would be condemned to hell because of the sins he believed she committed during her lifetime. He wrote: "God allows people to intercede for other people on the Day of Judgment if their wretchedness wasn't overwhelming. So my sole concern for my mother is to avoid Hell. After that, any rank in heaven would be great." ...

It fits within Hasan's established thinking to assume that if he believed that good deeds could be used in order to avoid his mother's suffering, he would have done whatever could be counted as the best of these prescribed good deeds. For Hasan, this was violent jihad. ...

n Hasan's motivations for committing violence and discussions of jihad, he makes it clear that he believed that violence against the U.S, who he considered an enemy, would be regarded as a good deed by God and would grant him a higher rank in heaven. This achievement was important to Hasan not just for his own sake, but for his mother's, as he thought his good deeds could be used to intercede and prevent her from going to hell. Furthermore, Hasan believed fighting to be commanded by God and obligatory, even if he did not want to do it.