Donald Trump first coined the phrase "extreme vetting" in July 2016, in the aftermath of the truck attack in Nice, France. For nine months, he and his advisors have been trying to figure out what this means in practice.

Their first iteration, announced on Jan. 27, just days after their coming to office, focused on countries, not individuals. This approach has twice been shot down by the courts; further, it inherently makes no sense: some Iranians are friends and some Canadians are enemies. Looking at countries is crude and ineffective.

Today, the Wall Street Journal reports on the second try at "Trump Administration Considers Far-Reaching Steps for 'Extreme Vetting'" by Laura Meckler.

It's good to hear that the authorities are taking this issue seriously. The new approach has two halves. The first is excellent, requiring that foreigners who wish to visit the United States "to answer probing questions about their ideology." In more detail: the "ideological test" will, according to a Department of Homeland Security official working on the review, include questions such as

whether visa applicants believe in so-called honor killings, how they view the treatment of women in society, whether they value the "sanctity of human life" and who they view as a legitimate target in a military operation.

These questions echo some of the 93 I laid out in "Smoking Out Islamists via Extreme Vetting." But I also discussed related research efforts and the manner of interviewing would-be visitors. So, this is a good start but it needs much more thought.

The other half focuses on electronic devices:

The biggest change to U.S. policy would be asking applicants to hand over their telephones so officials could examine their stored contacts and perhaps other information. ... A second change would ask applicants for their social-media handles and passwords so that officials could see information posted privately in addition to public posts.

"If they don't want to give us that information," Homeland Security Secretary John Kelly said in February, "then they don't come."

DHS Secretary John Kelly testifying before Congress. |

But this emphasis on electronics, especially mobile phones, won't work. With time, word will get out and anyone intending to make trouble will delete information or leave the device at home and get a burner phone. Leon Rodriguez, Obama's head of the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, notes that "The real bad guys will get rid of their phones. They'll show up with a clean phone. Over time, the utility of the exercise will diminish."

It won't be just "real bad guys" who take those steps. As a foreign policy analyst who frequently travels to other countries, I am a good guy; but I emphatically will not turn over my private information to foreign policemen and intelligence agencies; I'll do what is needed to avoid that, whether adjusting my devices or staying within the United States.

The person, not his country or telephone, must be the focus of attention. (April 4, 2017)

Jan. 20, 2025 update: A new Trump Administration means a new attempt to enforce extreme vetting (although that old term is no longer used, replaced by the clunkier "vetted and screened to the maximum degree possible"). Right on his first day back in office, Trump issued an executive order, "Protecting the United States from Foreign Terrorists and Other National Security and Public Safety Threats," to this effect. Excerpts:

To protect Americans, the United States must be vigilant during the visa-issuance process to ensure that those aliens approved for admission into the United States do not intend to harm Americans or our national interests. More importantly, the United States must identify them before their admission or entry into the United States. And the United States must ensure that admitted aliens and aliens otherwise already present in the United States do not bear hostile attitudes toward its citizens, culture, government, institutions, or founding principles, and do not advocate for, aid, or support designated foreign terrorists and other threats to our national security. ...

Recommend any actions necessary to protect the American people from the actions of foreign nationals who have undermined or seek to undermine the fundamental constitutional rights of the American people, including, but not limited to, our Citizens' rights to freedom of speech and the free exercise of religion protected by the First Amendment, who preach or call for sectarian violence, the overthrow or replacement of the culture on which our constitutional Republic stands, or who provide aid, advocacy, or support for foreign terrorists. ...

Evaluate the adequacy of programs designed to ensure the proper assimilation of lawful immigrants into the United States, and recommend any additional measures to be taken that promote a unified American identity and attachment to the Constitution, laws, and founding principles of the United States.

The order calls for a report on progress within 60 days, i.e., March 21.

Feb. 24, 2025 update: Finally, someone has picked up on the EO, being Josef Burton at The Nation. He is not a fan, calling this a "quieter, sneakier" version of the 2017 one.

A bland executive order buried in the January 20 flurry of White House proclamations doesn't name any country or even dictate specific policy. There is no lurid prose. ... The obtuse bureaucratic structures that were only created to legally justify the first ban now form the core structure of a new one that promises to be amorphous and adaptable to shifting policy needs. The intent, however, remains the same as it's always been: to deeply extend the power of the executive branch over the immigration system and to fulfill the wildest dreams of Trump's white-nationalist lackeys. ...

Burton decides that the issue really comes down to "Palestine":

This is a policy to deport or bar forever from the United States anyone who has publicly spoken in support of Palestine. Every group that participated in armed resistance against the Israeli genocide in Gaza was a US-designated terrorist organization. But even if your personal statements don't touch on the subject of armed resistance, US policy is to treat the Gaza municipality and local government as extensions of Hamas. Even a statement of praise for, say, firefighters or rescue workers from Gaza could, in theory, be a deportable offense for a foreigner legally in the US. A green card holder, married to an American citizen, could be deported and permanently banned from reuniting with their spouse for posting "from the river to the sea" on Instagram.

He also worries about academic programs:

What will become of the Fulbright program if subjects of study by foreign students are ruled in contravention of MAGA values? What about a postdoctoral program in women's studies? Or Black history? The new ban could also de facto close certain topics of academic research to foreign students. Foreign employees might find themselves banned as national security threats even if the conditions of their employment are completely legal and above board.

Feb. 27, 2025 update: The National Iranian American Council, informally known as Tehran's lobby in Washington, has protested the EO.

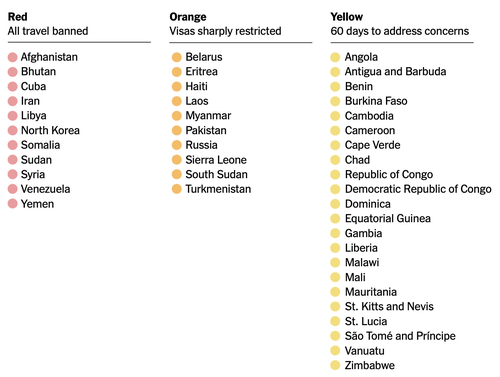

Mar. 14, 2025 update: An internal Trump administration proposal lists countries whose citizens could face restrictions on entering the United States.