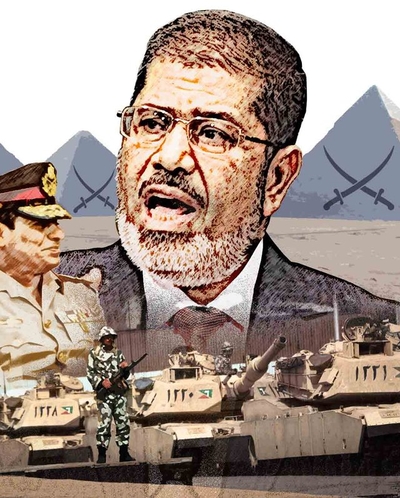

Earlier this year, most analysts in Egypt assessed Field Marshall Hussein Tantawi as the key figure in that country's politics and President Mohamed Morsi as a lightweight, so it came as a surprise when Morsi fired Tantawi on Aug. 12, 2012.

This matters because Tantawi would have kept the country out of Islamist hands while Morsi is speedily moving the country in the direction of applying Islamic law. If Morsi succeeds at this, the result will have major negative implications for America's standing in the region.

Abdel-Fattah al-Sisi, Egypt's new military boss. |

Tantawi, then the effective ruler of Egypt, had handpicked Morsi to become president, seeing him as the safest option, someone who could be manipulated or (if necessary) replaced. Toward this end, Tantawi instructed the Supreme Constitutional Court (SCC) to approve Morsi as a candidate, despite his arrest on Jan. 27, 2011, for "treason and espionage," his time in prison, and despite the SCC having excluded other Muslim Brotherhood candidates, especially the rich, charismatic, and visionary Khairat El-Shater, on the basis of their own imprisonment. Tantawi wanted the obscure, inelegant, and epileptic Morsi to run for president because Shater was too dangerous and another Brotherhood candidate, Abdel Moneim Aboul Fettouh, too popular.

Sometime after Morsi became president on June 30, Tantawi openly signaled his intent to overthrow him via a mass demonstration to take place on Aug. 24. His mouthpiece Tawfik Okasha openly encouraged a military coup against Morsi. But Morsi acted first and took several steps on Aug. 12: he annulled the constitutional declaration limiting his power, dismissed Tantawi, and replaced him with Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, the head of military intelligence.

Morsi, in brief, pre-empted the impending military coup d'état against him. Tarek al-Zomor, a leading jihadi and Morsi supporter, acknowledged that "choosing Sisi to replace Tantawi was to stop a coup," publicly acknowledging Morsi's urgent need to act before Aug. 24. Hamdi Kandil, one of Egypt's most prominent journalists, rightly characterized Morsi's act as "a civilian coup."

Tarek al-Zomor, a pro-Morsi violent Salafi, said publicly what others whispered. |

They missed one hidden factor: Brotherhood-oriented military officers turn out to have been far more numerous and powerful than previously realized: they both knew about the Aug. 24 plot plan and helped Morsi to beat it. If it was long apparent that some officers had an outlook sympathetic to the Brotherhood, the extent of their network has only just come out in the three months since the coup.

For example, we now know that Major General Abbas Mekheimar, the army officer assigned to oversee the purge of officers with Brotherhood or other Islamist affiliations, himself is aligned with the Brotherhood or perhaps a member of it. As for Sisi, while the Brotherhood denies his direct membership, one of its leaders says he belongs to its informal "family" – which makes sense, seeing that high-ranking public figures best advance its agenda when not formal members. His position as head of military intelligence gave him access to information about Tantawi's Aug. 24 planned coup and historian Ali Al-Ashmawi found that Sisi tracked military officials loyal to Tantawi and had them discharged.

Abbas Mekheimar, tasked with keeping the Muslim Brotherhood out of Egypt's military is aligned with the Muslim Brotherhood. |

Where does this leave matters? Tantawi and company are safely pensioned off, and (unlike Hosni Mubarak) are not going to jail. Sisi's military has retreated to roughly the same position that Tantawi's military occupied before Mubarak's overthrow in Feb. 2011, which is to say it is allied with the president and following his leadership without being fully subordinate to him. It retains control over its own budget, its promotions and dismissals, and its economic empire. But the military leadership lost the direct political power that it enjoyed for 1½ years in 2011-12.

Morsi's future is far from assured. Not only does he face competing factions of Islamists but Egypt faces a terrible economic crisis. Morsi's power today unquestionably brings major short-term benefits for himself and the Brotherhood; but in the long term it will likely discredit Brotherhood rule.

In short, following thirty years of stasis under Mubarak, Egypt's political drama has just begun.

Illustration by Greg Groesch for The Washington Times |

Mr. Pipes (www.DanielPipes.org) is president of and Ms Farahat an associate fellow at the Middle East Forum.. © 2012 by Daniel Pipes and Cynthia Farahat. All rights reserved.

Nov. 14, 2012 addendum: We ignored two other factors that did not fit above but contributed to Morsi's rise: (1) Tantawi sported a chest full of medals and multiple grandiose titles, but he was weak both nationally (where he represented the discredited old regime) and internationally (where he was seen as an obstacle to democracy). (2) However incompetent Morsi might be, smarter Brotherhood elements stood behind him (such as Khairat El-Shater, whose second name actually means "the clever one") and helped him plan his pre-emptive coup.

Nov. 20, 2012 update: That Shater is a power behind the scenes is confirmed in the Iraqi publication az-Zaman (made available by Al-Monitor), that Morsi is thinking to make him prime minister of Egypt:

Egypt's Muslim Brotherhood's official website said yesterday [Nov. 19] that the Egyptian presidency is considering replacing Prime Minister Hisham Kandil with Khairat al-Shater, the deputy leader of the group. … Ikhwanweb, the group's website, said that the Egyptian presidency is seriously considering entrusting the post of prime minister to Shater to replace Kandil, who was widely criticized following the Assiut bus accident that took place on Sunday morning [Nov. 18].

July 6, 2013 update: I learn today that Morsi and Sisi had ties before Morsi made Sisi the defense minister in August 2012. From a New York Times article, "Morsi Spurned Deals, Seeing Military as Tamed," explaining how Morsi got things so wrong in his relationship with Sisi:

Mr. Morsi never believed the generals would turn on him as long as he respected their autonomy and privileges, his advisers said. He had been the Muslim Brotherhood's designated envoy for talks with the ruling military council after the ouster of Mr. Mubarak. And his counterpart on the council was Gen. Abdul-Fattah el-Sisi.

The Brotherhood was naturally suspicious of the military, its historical opponent, but General Sisi cultivated Mr. Morsi and other leaders, one of them said, including going out of his way to show that he was a pious Muslim. "That is how the relationship between the two of them started," said a senior Brotherhood official close to Mr. Morsi. "He trusted him."

The two grew so close that Mr. Morsi caught his advisers by surprise when he promoted General Sisi to defense minister last summer as part of a deal that persuaded the military for the first time to let the president take full control of his government. The relationship with the military was Mr. Morsi's "personal file," one adviser said.

That bond began soon to fall apart, however:

But during the fall protests charging the Brotherhood with monopolizing power, General Sisi first signaled that his departure from politics might not be so permanent. Without consulting Mr. Morsi, General Sisi publicly invited all the country's political factions — from social democrats to ultraconservative sheiks — to a meeting to try to hammer out a compromise on a more inclusive government. Mr. Morsi quashed the idea, advisers said.

General Sisi said publicly last week he continued after that to try to broker some compromise with the opposition and to ease the paralysis of Egyptian politics. It was at that point, Mr. Morsi's advisers say, that they first suspected General Sisi of intrigue.

Mr. Morsi, they say, often pressed General Sisi to stop the threatening or disparaging statements toward the president from unnamed military officials in the news media. General Sisi merely said "newspapers and media exaggerate," and that he was "trying to control the tensions toward the president inside the military," one adviser said.

Yet Mr. Morsi insisted to his aides that he remained fully confident that General Sisi would not interfere, his advisers said. Mr. Morsi was the last one in the inner circle to acknowledge that General Sisi was ousting them.

That process of ousting began on June 21,

when General Sisi issued a public statement warning that the growing "split in society" between Mr. Morsi's supporters and opponents compelled the military "to intervene." Mr. Morsi was given no warning, his advisers said. But when Mr. Morsi called the general, General Sisi told the president that "it was to satisfy some of his men" and that "it was nothing more than an attempt to absorb their anger," one of Mr. Morsi's advisers said. "So even after that first statement, the president didn't think a coup was imminent."

The day before the protests, General Sisi called Mr. Morsi to press him for a package of concessions, including a new cabinet. But Mr. Morsi refused, saying he needed to consult first with his Islamist coalition.

At that point, Morsi entered his own zone of reality.