"One Godless Woman" frying bacon while wearing a bikini. |

Beyond such provocations, ex-Muslims work to change the image of Islam. Wafa Sultan went on Al Jazeera television to excoriate Islam in an exalted Arabic and over 30 million viewers watched the ensuing video. Ayaan Hirsi Ali wrote a powerful autobiography about growing up female in Somalia and went on to author high-profile books criticizing Islam. Ibn Warraq wrote or edited a small library of influential books on his former religion, including Why I am Not a Muslim (1995) and Leaving Islam: Apostates Speak Out (2003).

Behind these individuals stand Western-based organizations of ex-Muslims that encourage Muslims to renounce their faith, provide support to those who have already taken this step, and lobby against Islam with the knowledge of insiders and the passion of renegades.

Together, these phenomena point to an unprecedented shift: the historically illegal and unspeakable actions among Muslims of open disbelief in God and rejection of Muhammad's mission has spread to the point that it shakes the Islamic faith.

To non-Muslims, this shift tends to be nearly invisible and therefore is dismissed as marginal. When it comes to Arabs, Ahmed Benchemsi notes, Westerners see religiosity as "an unquestionable given, almost an ethnic mandate embedded in their DNA." The Islamist surge may have peaked nearly a decade ago but the eminent historian Phillip Jenkins confidently states that, "By no rational standard can Saudi Arabia, say, be said to be moving in secular directions."

To help rectify this misunderstanding, the following analysis documents the phenomenon of Muslims becoming atheists. By atheist, along with the organization Ex-Muslims of North America, I mean Muslims "who adopt no positive belief of a deity," including "agnostics, pantheists, freethinkers, and humanists." Atheist emphatically does not, however, include Muslims who convert to Christianity (the topic of a separate study by this author) or to any other religion.

To help rectify this misunderstanding, the following analysis documents the phenomenon of Muslims becoming atheists. By atheist, along with the organization Ex-Muslims of North America, I mean Muslims "who adopt no positive belief of a deity," including "agnostics, pantheists, freethinkers, and humanists." Atheist emphatically does not, however, include Muslims who convert to Christianity (the topic of a separate study by this author) or to any other religion.

Hidden Atheists

Two main factors make it difficult to estimate the number of ex-Muslim atheists.

Nasr Abu Zayd (1943-2010). |

The path of reform itself, however, is fraught with dangers. The eminent Egyptian authority on Islam, Nasr Abu Zayd, insisted he remained a Muslim but his opponents, perhaps motivated by financial considerations, deemed him an apostate and succeeded in both annulling his marriage and forcing him to flee from Egypt. Worse, the Sudanese government executed the great Islamic thinker Mahmoud Mohammed Taha as an apostate.

Second, overtly declaring oneself an atheist invites punishments that range from ostracizing to beating, to firing, to jailing, to murder. Families see atheists as blots on their honor. Employers see them as untrustworthy. Communities see them as traitors. Governments see them as national security threats. Lest this last seem absurd, the authorities realize that what starts with individual decisions grows into small groups, gathers force, and can culminate in the seizure of power. In the most extreme reaction, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia promulgated anti-terrorist regulations on March 7, 2014, that prohibit "Calling for atheist thought in any form, or calling into question the fundamentals of the Islamic religion on which this country is based." In other words, freethinking equates to terrorism.

Indeed, many Muslim-majority countries formally punish apostasy with execution, including Mauritania, Libya, Somalia, Yemen, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, Iran, Afghanistan, Malaysia, and Brunei. Formal executions tend to be rare but the threat hangs over apostates. Sometimes, death does follow: A Nigerian, Mubarak Bala, was arrested and disappeared for his blasphemous statements. In a case that attracted global attention, Ayatollah Khomeini called on freelancers to murder Salman Rushdie in 1989 for writing The Satanic Verses, a magical-realist novel containing disrespectful scenes about Muhammad. Vigilante violence also occurs; in Pakistan, preachers called on mobs to burn down the houses of apostates.

Indeed, many Muslim-majority countries formally punish apostasy with execution, including Mauritania, Libya, Somalia, Yemen, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, Iran, Afghanistan, Malaysia, and Brunei. Formal executions tend to be rare but the threat hangs over apostates. Sometimes, death does follow: A Nigerian, Mubarak Bala, was arrested and disappeared for his blasphemous statements. In a case that attracted global attention, Ayatollah Khomeini called on freelancers to murder Salman Rushdie in 1989 for writing The Satanic Verses, a magical-realist novel containing disrespectful scenes about Muhammad. Vigilante violence also occurs; in Pakistan, preachers called on mobs to burn down the houses of apostates.

This external pressure at least partially succeeds, notes Iman Willoughby, a Saudi refugee living in Canada: "the Middle East would be significantly more secular if it was not for heavy-handed religious government enforcement or the power mosques are given to monitor communities." Fearful of trouble, more than a few ex-Muslims hide their views and maintain the trappings of believers, making them effectively uncountable.

Numbers Estimated

Nonetheless, Willoughby observes, "Atheism is spreading like wildfire" in the Middle East. Hasan Suroor, author of Who Killed Liberal Islam?, notes that there's a tale "we don't usually hear about how Islam is facing a wave of desertion by young Muslims suffering from a crisis of faith, ... abandoned by moderate Muslims, mostly young men and women, ill at ease with growing extremism in their communities. ... Even deeply conservative countries with strict anti-apostasy regimes like Pakistan, Iran and Sudan have been hit by desertions." That tale, however, is now more public: "I know at least six atheists who confirmed that [they are atheists] to me," noted Fahad AlFahad, 31, a marketing consultant and human rights activist in Saudi Arabia, in 2014. "Six or seven years ago, I wouldn't even have heard one person say that. Not even a best friend would confess that to me," but the mood has changed and now they feel freer to divulge this dangerous secret.

Whitaker concludes that Arab non-believers "are not a new phenomenon but their numbers seem to be growing." Momen, an Egyptian adds, "My guess is, every Egyptian family contains an atheist, or at least someone with critical ideas about Islam." Professor Amna Nusayr of al-Azhar University states that 4 million Egyptians have left Islam. Todd Nettleton finds that, by some estimates, "70 percent of Iran's people have rejected Islam."

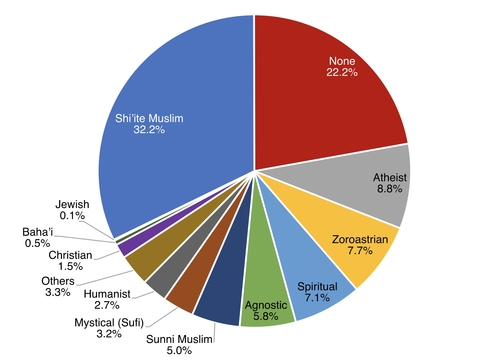

Turning to survey research, a WIN/Gallup survey in 2012 found that "convinced atheists" make up 2 percent of the population in Lebanon, Pakistan, Turkey, and Uzbekistan; 4 percent in the West Bank and Gaza; and 5 percent in Saudi Arabia. Revealingly, the same poll found "not religious" persons to be more numerous: 8 percent in Pakistan, 16 percent in Uzbekistan, 19 percent in Saudi Arabia, 29 percent in the West Bank and Gaza, 33 percent in Lebanon, and 73 percent in Turkey. Conversely, a GAMAAN poll found that just one-third, or 32.2 percent, of born Shi'ite Muslims in Iran actually identify as such, plus 5 percent as Sunnis and 3.2 percent as Sufis.

GAMAAN's 2020 survey on Iranian attitudes toward religion. |

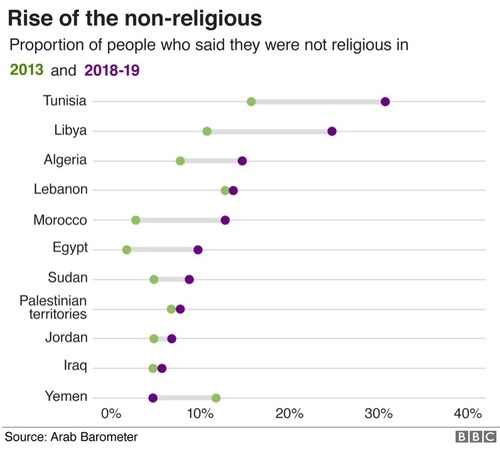

The trend is upwards: a Konda survey in Turkey found that atheists tripled from 1 to 3 percent between 2008 and 2018, while non-believers doubled from 1 to 2 percent. Arab Barometer polls show a substantial increase in the number of Arabic-speakers who say they are "not religious," from 8 percent in 2012-14 to 13 percent in 2018-19, a 61 percent increase in five years. This trend is yet greater among 15-29-year-olds, among whom the percentage went from 11 to 18 percent. Looking country by country, the largest increases occurred in Tunisia and Libya, with middle-sized ones in Morocco, Algeria, Egypt, and Sudan, and almost no change in Lebanon, the Palestinian territories, Jordan, and Iraq. Yemen stands out as the one country to count fewer non-religious persons. It is particularly striking to note that about as many Tunisian youth (47 percent) as American (46 percent) call themselves "not religious."

Many indications point to the number of atheists as large and growing.

Importance

Atheism among Muslim-born populations historically has been of minor importance and it appeared especially negligible during the surge of Islamism over the past half-century. When this writer coined the formula after 9/11, "Radical Islam is the problem, moderate Islam is the solution," atheism among Muslims was nearly undetectable. But no longer. The passage of twenty years finds undertow of atheism having turned into a significant force, one with the potential to affect not just the lives of individuals but also societies and even governments.

It enjoys such potency because contemporary Islam, with its repression of heterodox ideas and punishment of anyone who leaves the faith, is singularly vulnerable to challenge. Just as an authoritarian regime is more brittle than a democratic one, so Islam as practiced today lacks the suppleness to deal with internal critics and rebels. The result is an Islamic future more precarious than its past.

Mr. Pipes (DanielPipes.org, @DanielPipes) is president of the Middle East Forum. © 2021 by Daniel Pipes. All rights reserved.

Feb. 24, 2024 update: The Iranian Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance sponsored a large-scale poll that found

85 percent said Iranians have become less religious compared to 5 years ago. Only 7 percent said they have become more religious and around 8 percent said they can see no difference in this regard between now and 5 years ago. 5Looking ahead, over 81 percent anticipate a continued decline in religious observance over the next five years, reflecting shifting societal attitudes towards religious practices. Only 9 percent said they are likely to be more religious and around 10 percent said there will be no difference.