The stabbing of Salman Rushdie sends a renewed message to the world: take Islamism – the transformation of the Islamic faith into a radical utopian ideology inspired by medieval goals – seriously. Unlike Rushdie himself.

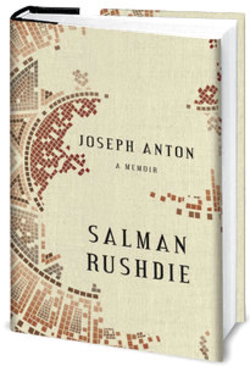

Joseph Anton: A Memoir recounts Salman Rushdie's years hiding from Islamists. |

Already during those years, however, Rushdie made several feints to convince himself that the edict was relaxing. In 1990, he disavowed elements in his book that question the Quran or challenge Islam; his opponents rightly dismissed this as deceit, but Rushdie insisted, "I feel a lot safer tonight than I felt yesterday."

In 1998, after some mumbled concessions by Iranian officials, Rushdie triumphantly declared his troubles entirely over: "There is no longer any threat from the Iranian regime. The fatwa will be left to wither on the vine. ... When you're so used to getting ... bad news, then news like this is almost unbelievable. It's like being told the cancer is gone. Well, the cancer's gone."

So convinced was Rushdie that the threat had vaporized, he upbraided the organizers of the 11th Prague Writers' Festival in 2001 for the security they arranged for him: "to be here and find a relatively large security operation around me has actually felt a little embarrassing, because I thought it was really unnecessary and kind of excessive and was certainly not arranged on my request. I spent a great deal of time before I came here saying that I really didn't want that. So I was very surprised to arrive here and discover a really quite substantial operation, because it felt like being in a time warp, that I had gone back in time several years."

In 2003, Rushdie had his friend, the writer Christopher Hitchens, admonish me for my multiple published warnings to Rushdie (six in all), pleading that he realise Khomeini's edict could never be lifted, reminding him that any fanatic might at any time assault him. Hitchens criticized my "sour, sophomoric" analysis, my insisting "that nothing whatsoever had changed" to Rushdie's predicament. He refuted my pessimism by chirpily reporting how "today, Salman Rushdie lives in New York without body guards and travels freely."

Christopher Hitchens (L) and Salman Rushdie. |

In 2017, Rushdie both criticized the Quran ("not a very enjoyable book") and mocked the death edict on a comedy show, boasting of its compensations, notably what he called "fatwa sex" with women attracted to danger.

In 2021, he surprisingly acknowledged his own addiction to illusion: "It's true, I am stupidly optimistic, and I think it did get me through those bad years, because I believed there would be a happy ending, when very few people did believe it."

Finally, in 2022, only days before his stabbing, Rushdie proclaimed the edict was "all a long time ago. Nowadays my life is very normal again." Asked what he fears, Rushdie replied "In the past I would have said religious fanaticism. I no longer say that. The biggest danger facing us right now is losing our democracy," then referring to the U.S. Supreme Court deciding abortion is not a constitutional right.

As Rushdie and his friends thought the edict a thing of the past, his Islamist enemies unendingly reiterated that the death sentence remained in place, that they eventually would get him. And indeed they did; it took one-third of a century but the attack finally came as Rushdie presented himself, unprotected, to the public.

The scene moments after Hadi Matar stabbed Salman Rushdie. |

Will the rest of us learn from this sad tale of mixed fanaticism and illusion? Russia and China are certainly great power foes, but Islamism is an ideological threat. Its practitioners range from the rabid (ISIS) to the totalitarian (the Islamic Republic of Iran) to the mock-friendly (the Turkey of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan). They threaten via propaganda, subversion, and violence. They mobilise not just in the caves of Afghanistan but in idyllic resort towns like Chautauqua, New York.

May Salman Rushdie return to complete health and his suffering serve as a warning against wishful thinking.

Mr. Pipes is author of The Rushdie Affair (1990) and president of the Middle East Forum.

Feb. 21, 2025 update: A jury found Hadi Matar guilty of attempted murder.

May 16, 2025 update: After Hadi Matar called Rushdie a hypocrite and a bully, Judge David W. Foley sentenced him to 25 years in prison for attempted murder. Matar intends to appeal; he next faces federal charges of terrorism.