Critics of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA), the organization tasked with oversight of Palestine refugees, have tended to focus on its sins. Its camps are havens for terrorists. Its bureaucracy is bloated and its payroll includes radicals. Its schools teach incitement. Its registration rolls reek with fraud. Its policies encourage a mentality of victimhood.

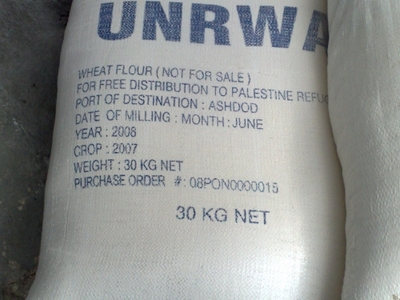

Food distribution now constitutes a small part of UNRWA's spending; most of it concerns education and health. |

Further, UNRWA violates the Refugee Convention by insisting that nearly two million people who have been given citizenship in Jordan, Syria, and Lebanon (and who constitute 40 percent of UNRWA's beneficiaries) are still refugees.

As a result of such practices, instead of going down through resettlement and natural attrition, the number of UNRWA refugees has steadily grown since 1949, from 750,000 to almost 5 million. At this rate, UNRWA refugees will exceed 8 million by 2030 and 20 million by 2060, its camps and schools endlessly promoting the futile dream that these millions of descendants someday will "return" to their ancestors' homes in Israel. When even Palestinian Authority chairman Mahmoud Abbas acknowledges that sending five million Palestinians would mean "the end of Israel," it's clear that UNRWA obstructs conflict resolution.

Israeli government officials are well aware that UNRWA perpetuates the refugee problem and full well know its sins. That said, the State of Israel has a working relationship with UNRWA and looks to it to fulfill certain services.

Israel's cooperative policy began in 1967 with the Comay-Michelmore Exchange of Letters in which Jerusalem promised "the full co-operation of the Israel authorities ... [to] facilitate the task of UNRWA." This policy remains in very much place; in November 2009, an Israeli representative confirmed a "continued commitment to the understandings" of the 1967 letters and support for "UNRWA's important humanitarian mission." He even promised to maintain "close coordination" with UNRWA.

Mural of Ayat al-Akhras, a Palestinian suicide bomber, on the wall of an UNWRA school in the Deheishe Refugee Camp near Bethlehem; despite incitement like this, the Israeli government does not want UNRWA's work shut down. (Photo by Rhonda Spivak) |

As a well-informed Israeli official sums it up, UNRWA plays a "key role in supplying humanitarian assistance to the civilian Palestinian population" that must be sustained.

This explains why, when foreign friends of Israel try to defund UNRWA, Jerusalem urges caution or even obstructs these efforts. For example, in January 2010, Canada's Harper government announced that it would redirect aid from UNRWA to the Palestinian Authority to "ensure accountability and foster democracy in the PA." Although B'nai B'rith Canada proudly reported that "the government listened" to its advice, Canadian diplomats said that Jerusalem quietly requested the Canadians to resume funding UNRWA.

Another example: in December 2011, the Dutch foreign minister said that his government would "thoroughly review" its policy toward UNRWA, only later to tell confidants that Jerusalem had asked him to leave UNRWA's funding alone.

Which brings us to the question: Can the elements of UNRWA useful to Israel be retained without perpetuating the refugee status?

Yes, but this requires distinguishing UNRWA's role as a social service agency from its role producing ever-more "refugees." Contrary to its practice of registering grandchildren as refugees, Section III.A.2 and Section III.B of UNRWA's Consolidated Eligibility & Registration Instructions allow it to provide social services to Palestinians without defining them as refugees. This provision is already in effect: in the West Bank, for example, 17 percent of the Palestinians registered with UNRWA in January 2012 and eligible to receive its services were not listed as refugees.

Given that UNRWA reports to the U.N. General Assembly, with its automatic anti-Israel majority, mandating a change in UNRWA practices is nearly impossible. But major UNRWA donors, starting with the US government, should stop being accomplices to UNRWA's perpetuation of the refugee status.

Washington should treat UNRWA as a vehicle to deliver social services, nothing more. It should insist that UNRWA beneficiaries who either were never displaced or who have already have citizenship in other countries, although perhaps eligible for UNRWA services, are not refugees. Establishing this distinction reduces a key irritant in Arab-Israeli relations.

Steven J. Rosen heads the Washington Project of the Middle East Forum and Daniel Pipes is president of the Forum. © 2012 by Steven J. Rosen and Daniel Pipes.