Daniel Pipes, one of our leading experts on Islam, established the Middle East Forum and became its head in 1994. He was born in 1949 and grew up in Cambridge, Massachusetts. His father, Richard Pipes, was a professor of Russian history, now emeritus, at Harvard.

Tom Bethell.

Daniel studied Arabic and Islamic history and lived in Cairo for three years. His PhD dissertation became his first book, Slave Soldiers and Islam (1981). Then his interest in purely academic subjects expanded to include modern Islam. He left the university because, as he told an interviewer from Harvard Magazine, he has "the simple politics of a truck driver, not the complex ones of an academic."

His story of being harassed through the legal system by a Muslim who later committed suicide was recently told in The American Spectator ("A Palestinian in Texas," TAS, November 2012). He has been personally threatened but prefers not to talk about specifics except to note that law enforcement has been involved.

I interviewed Pipes shortly before Christmas, when the Egyptians were voting on their new constitution. I started out by saying that the number of Muslims in the U.S. has doubled since the 9/11 attacks.

DP: My career divides in two: before and after 9/11. In the first part I was trying to show that Islam is relevant to political concerns. If you want to understand Muslims, I argued, you need to understand the role of Islam in their lives. Now that seems obvious. If anything, there's a tendency to over-emphasize Islam; to assume that Muslims are dominated by the Koran and are its automatons—which goes too far. You can't just read the Koran to understand Muslim life. You have to look at history, at personalities, at economics, and so on.

DP: My career divides in two: before and after 9/11. In the first part I was trying to show that Islam is relevant to political concerns. If you want to understand Muslims, I argued, you need to understand the role of Islam in their lives. Now that seems obvious. If anything, there's a tendency to over-emphasize Islam; to assume that Muslims are dominated by the Koran and are its automatons—which goes too far. You can't just read the Koran to understand Muslim life. You have to look at history, at personalities, at economics, and so on.

TB: Do you see the revival of Islam as a reality?

DP: Yes. Half a century ago Islam was waning, the application of its laws became ever more remote, and the sense existed that Islam, like other religions, was in decline. Since then there has been a sharp and I think indisputable reversal. We're all talking about Islam and its laws now.

TB: At the same time you have raised an odd question: "Can Islam survive Islamism?" Can you explain that?

DP: I draw a distinction between traditional Islam and Islamism. Islamism emerged in its modern form in the 1920s and is driven by a belief that Muslims can be strong and rich again if they follow the Islamic law severely and in its entirety. This is a response to the trauma of modern Islam. And yet this form of Islam is doing deep damage to faith, to the point that I wonder if Islam will ever recover.

TB: Give us the historical context.

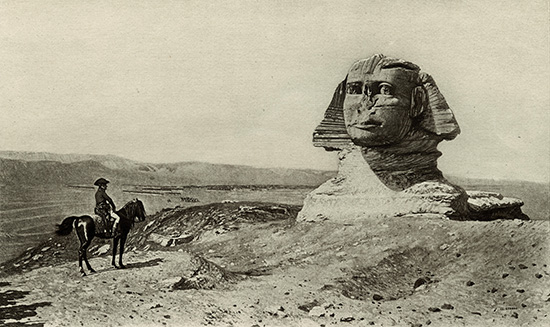

DP: The modern era for Muslims began with Napoleon's invasion of Egypt in 1798. Muslims experienced a great shock at seeing how advanced the blue-eyed peoples from the north had become. It would be roughly analogous to the Eskimos coming down south and decimating Westerners, who would uncomprehendingly ask in response, "Who are these people and how are they defeating us?"

Jean-León Gérôme's imaginary vision of Napoleon facing the Sphinx. |

TB: So how did they respond?

DP: Muslims over the past 200 years have made many efforts to figure out what went wrong. They have experimented with several answers. One was to emulate liberal Europe—Britain and France—until about 1920. Another was to emulate illiberal Europe—Germany and Russia—until about 1970. The third was to go back to what are imagined to be the sources of Islamic strength a millennium ago, namely the application of Islamic law. That's Islamism. It's a modern phenomenon, and it's making Muslims the center of world unrest.

TB: But it is also creating discomfort?

DP: It has terribly deleterious effects on Muslims. Many of them are put off by Islam. In Iran, for example, one finds a lot of alienation from Islam as a result of the Islamist rule of the last 30-odd years.

TB: Has it happened anywhere else?

DP: One hears reports, especially from Algeria and Iraq, of Muslims converting to Christianity. And in an unprecedented move, ex-Muslims living in the West have organized with the goal of becoming a political force. I believe the first such effort was the Centraal Comité voor Ex-moslims in the Netherlands, but now it's all over the place.

TB: Nonetheless, Islam has lasted for 1,500 years.

DP: Yes, but modern Islamism has been around only since the 1920s, and I predict it will not last as a world-threatening force for more than a few decades. Will Muslims leave the faith or simply stop practicing it? These are the sort of questions I expect to be current before long.

TB: What about Islam in the United States?

DP: In the long term, the United States could greatly benefit Islam by uniquely freeing the religion from government constraints and permitting it to evolve in a positive, modern direction. But that's the long term. Right now, American Muslims labor under Saudi and other influences, their institutions are extreme, and things are heading in a destructive direction. It's also distressing to see how non-Muslim individuals and institutions, particularly those on the left, indulge Islamist misbehavior.

TB: How do they do that?

DP: Well, turn on the television, go to a class, follow the work of the ACLU or the Southern Poverty Law Center, and you will see corporations, nonprofits, and government institutions working with the Islamists, helping promote the Islamist agenda. The American left and the Islamists agree on what they dislike—conservatives—and, despite their profound differences, they cooperate.

TB: Presumably some Muslims here deconvert, right?

DP: There are some conversions out of Islam, yes. And the Muslim establishment in this country is quite concerned about that. But numerically it is not a significant number.

TB: The ones who convert don't talk about it very much?

DP: In some cases they do; they take advantage of Western freedoms to speak their minds. They are the exceptions, though.

TB: I suspect that the decline of Christianity has encouraged Islam.

DP: Very much so, as the contrast between Europe and the United States reveals. The hard kernel of American Christian faith, not present in Europe, means that Islamists are far better behaved in the United States. They see the importance of a Christian counterforce.

TB: Earlier, you mentioned Algeria. It is a big Muslim state that we don't hear about today.

DP: Twenty years ago Algeria was a major focus of attention. That long ago ended, although in France coverage is still significant. Algeria is ripe for the same kind of upheaval that we have seen in other North African states, such as Tunisia, Libya, and Egypt. I think it is likely to happen before too long.

Said one month before the In Amenas attack: "Algeria is ripe for the same kind of upheaval that we have seen in other North African states. ... I think it is likely to happen before too long." |

TB: What about Syria?

DP: Assad's power is steadily diminishing and I cannot see how his regime will remain long in power.

TB: Should the United States get involved there?

DP: No, Americans have no dog in this fight and nothing in the U.S. Constitution requires us to get involved in every foreign conflict. Two wretched forces are killing each other; just look at the ghastly videos of the two sides torturing and executing the other. Listen also to what they are saying. It's a civil war involving the bad and the worse. I don't want the U.S. government involved. That would mean bearing some moral responsibility for what emerges, which I expect to be very unsavory.

TB: So you are supporting the Obama position?

DP: Yes, though he reaches it with far more angst. Also, there appears to be some serious, clandestine U.S. support for the rebel forces. The September 11 meeting in Benghazi between the Turkish and the American ambassadors was very curious. They are both based in Tripoli, hundreds of miles away. What were they doing in Benghazi? Arranging for American arms going via Turkey to Syria, it appears.

TB: How important has Israel been to the revival of Islam?

DP: It is a major factor in the neighboring states. But elsewhere, in Morocco, Iran, Malaysia, it has minor importance.

TB: Since the "Arab Spring," Israel seems increasingly beleaguered.

DP: Not really, not yet, though I agree that it will be more beleaguered with time. Its neighbors are so consumed with their own affairs that they hardly pay Israel attention. But once the neighbors get their houses in order, Israel will most likely face new difficulties.

TB: You have questioned U.S. support for Islamic democracy, which does seem naïve.

DP: The U.S. has been the patron for democracy for a century, since Wilson's 14 Points, and a wonderful heritage it has been. When an American travels the world, he finds himself in country after country where his country played a monumentally positive role, especially in democratizing the system. We naturally want to extend this to Muslim-majority countries. Sadly, these for some time have offered an unpleasant choice between brutal and greedy dictators or ideological, extreme, and antagonistic elected Islamists. It's not a choice we should accept.

TB: So what should we do?

DP: I offer three simple guidelines. One, always oppose the Islamists. Like fascists and Communists, they are the totalitarian enemy, whether they wear long beards in Pakistan or suits in Washington.

Two, always support the liberal, modern, secular people who share our worldview. They look to us for moral and other sustenance; we should be true to them. They are not that strong, and cannot take power soon anywhere, but they represent hope, offering the Muslim world's only prospect of escape from the dreary dichotomy of dictatorship or extremism.

Three, and more difficult, cooperate with dictators but condition it on pushing them toward reform and opening up. We need the Mubaraks of the world and they need us. Fine, but relentlessly keep the pressure on them to improve their rule. Had we begun this process with Abdullah Saleh of Yemen in 1978 or with Mubarak in 1981, things could have been very different by 2011. But we didn't.

TB: Egypt might be the test case.

DP: Well, it's a bit late. Mohammed Morsi is not a greedy dictator but he emerged from the Muslim Brotherhood, and his efforts since reaching power have been purely Islamist.

TB: What about the recent elections?

DP: I do not believe that a single one of the elections and referenda in Egypt was fairly conducted. It surprises me that Western governments and media are so gullible on this score.

TB: You could say we were supporting the democracy element in Cairo's Tahrir Square. Were we not?

DP: Yes and rightly so. The initial demonstrations of early 2011 were spearheaded by the liberals and seculars who deserve U.S. support. But they got quickly pushed aside and Washington barely paid them further attention.

TB: We gave foreign aid to Mubarak. Was that a bad idea?

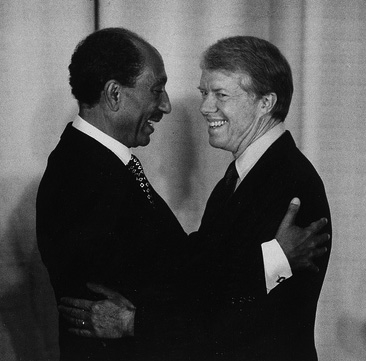

DP: That aid dates back to the utterly different circumstances of the Egypt-Israel peace treaty of 1979 and became progressively more wrong-headed. It should long ago have been discontinued. More broadly, I believe in aid for emergencies (soup and blankets) and as a bribe, but not for economic development. That the Obama administration is contemplating aid, including military hardware, to the Morsi government outrages me.

U.S. aid to Egypt dates from a different era -- Anwar el-Sadat and Jimmy Carter in 1979. |

Tom Bethell is a senior editor of The American Spectator and author of The Politically Incorrect Guide to Science, The Noblest Triumph: Property and Prosperity Through the Ages, and most recently Questioning Einstein: Is Relativity Necessary? (2009).