His honors are manifold – Ford Professor of Political Science Emeritus at the University of California, Berkeley, Adjunct Professor of Political Science at Columbia University, former President of the American Political Science Association and a recipient of its James Madison Award, fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences - and he has written many acclaimed books.

But Waltz has also published in the July/August issue of Foreign Affairs the single most preposterous analysis by an allegedly serious strategist of the Iranian quest for a nuclear weapon. His title and subtitle neatly sum up his argument: "Why Iran Should Get the Bomb: Nuclear Balancing Would Mean Stability." Here are three gem-like reasons he offers for wanting an Iranian bomb, as helpfully summarized in a letter to Council on Foreign Relations members:

It would produce a more stable balance of military power in the Middle East: "Israel's regional nuclear monopoly, which has proved remarkably durable for the past four decades, has long fueled instability in the Middle East... It is Israel's nuclear arsenal, not Iran's desire for one, that has contributed most to the current crisis...In fact, by reducing imbalances in military power, new nuclear states generally produce more regional and international stability, not less."

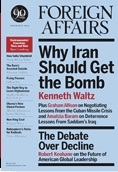

Foreign Affairs' clever graphic for the Kenneth Waltz article urging Iranian nuclear weapons.

It would reduce the risk of war between Israel and Iran: "If Iran goes nuclear, Israel and Iran will deter each other, as nuclear powers always have. There has never been a full-scale war between two nuclear-armed states. Once Iran crosses the nuclear threshold, deterrence will apply, even if the Iranian arsenal is relatively small."

It would produce a more cautious Iran: "History shows that when countries acquire the bomb, they feel increasingly vulnerable and become acutely aware that their nuclear weapons make them a potential target in the eyes of major powers...Maoist China, for example, became much less bellicose after acquiring nuclear weapons in 1964, and India and Pakistan have both become more cautious since going nuclear."

Comments:

(1) Israel's nuclear monopoly has fueled instability in the Middle East? Apocalyptic Iranian leaders will abide by deterrence theory or become more cautious? Clearly, Waltz knows nothing about the Arab-Israeli conflict or the Islamic Republic of Iran. He would have done himself a favor by keeping his mouth shut.

(2) What possessed Foreign Affairs to publish this rubbish Waltz has been peddling for years? Even more remarkably, what genius decided to make this the screaming headline on the cover?

(2) What possessed Foreign Affairs to publish this rubbish Waltz has been peddling for years? Even more remarkably, what genius decided to make this the screaming headline on the cover?

(3) This article prompts one of those moments – the journal's endorsement of John J. Mearsheimer and Stephen M. Walt's article, "The Israel Lobby and U.S. Foreign Policy" being another – when I am very sorely tempted to drop my membership in the Council on Foreign Relations.

(4) And yet again, one shakes one's head at the sickly results of a too-isolated ivory tower. (July 1, 2012)

Sep. 16, 2012 update: Israel's prime minister Binyamin Netanyahu used the same words as me, practically, in referring to the Waltz thesis: "Some have even said that Iran with nuclear weapons would stabilize the Middle East. I think the people who say this have set a new standard for human stupidity."

June 5, 2017 update: In a wonderfully perceptive article, "The Real Gap: Why Scholars and Policymakers Disagree," Hal Brands explains how "those who study international security and those who practice it see the same world through very different conceptual lenses," and what differences in outlook this leads to. Basically, it comes down to (a) academics needing to impress their peers and (b) living in a neat theoretical world where mistakes have no consequences. In this context, he mentions Waltz's notorious Foreign Affairs article as an example of the extreme disconnect between reality and political science.

Speaking of political science: Brands' indictment of international relations scholarship never once mentions the study of history (even though he himself is a historian), yet his entire argument points to knowledge of history, not political "science" as the best preparation for real-world decisionmaking.