Rebellion has shaken Turkey since May 31: Is it comparable to the Arab upheavals that overthrew four rulers since 2011, to Iran's Green Movement of 2009 that led to an apparent reformer being elected president last week, or perhaps to Occupy Wall Street, which had negligible consequences?

The government of Istanbul told mothers to "bring their children home" but instead they joined the protests in Taksim Square. |

China-like material growth has been the main achievement of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and the party he heads, the AKP. Personal income has more than doubled in the decade that he has been in power, changing the face of the country. As a visitor to Turkey since 1972, I have seen the impact of this growth in almost every area of life, from what people eat to their sense of Turkish identity.

That impressive growth explains the AKP's increased share of the national vote in its three elections, from 34 percent in 2002 to 46 percent in 2007 to a shade under 50 percent in 2011. It also explains how, after 90 years of the military serving as the ultimate political power, the party was able to bring the armed forces to heel.

At the same time, two vulnerabilities have become more evident, especially since the June 2011 elections, jeopardizing Erdoğan's continued domination of the government.

Dependence on foreign credit. To sustain consumer spending, Turkish banks have borrowed heavily abroad, and especially from supportive Sunni Muslim sources. The resulting current account deficit creates so great a need for credit that the private sector alone needs to borrow US$221 billion in 2013, or nearly 30 percent of the country's $775 billion GDP. Should the money stop flowing into Turkey, the party (pun intended) is over, possibly leading the stock market to collapse, the currency to plunge, and the economic miracle to come to a screeching halt.

Erdoğan instructs parents, "I am watching you. You will make at least three children." |

These two weaknesses point to the importance of the economy for the future of Erdoğan, the AKP, and the country. Should Turkey's finances weather the demonstrations, the Islamist program that lies at the heart of the AKP's platform will continue to advance, if more cautiously. Perhaps Erdoğan himself will remain leader, becoming the country's president with newly enhanced powers next year; or perhaps his party will tire of him and – as happened to Margaret Thatcher in 1990 – push him aside in favor of someone who can carry out the same program without provoking so much hostility.

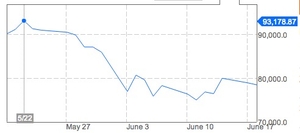

After two weeks of demonstrations, the Istanbul stock exchange lost nearly 10 percent of its value. |

Payroll employment is down by 5 percent. Real consumer spending in first quarter 2013 fell by 2 percent over 2012. Since the demonstrations started, the Istanbul stock market is down 10 percent and interest rates are up about 50 percent. To assess the future of Islamism in Turkey, watch these and other economic indicators.

Mr. Pipes (DanielPipes.org) is president of the Middle East Forum. © 2013 by Daniel Pipes. All rights reserved.

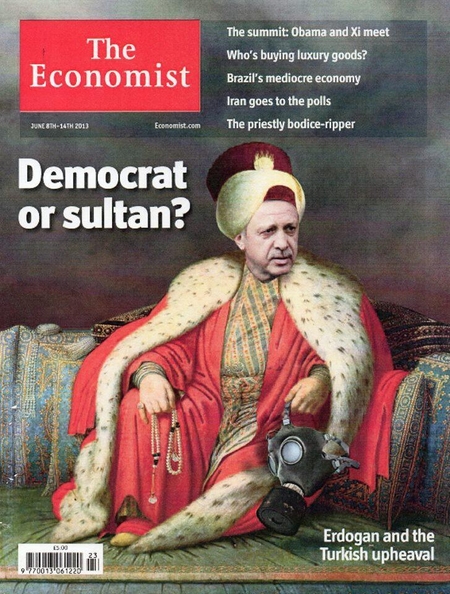

June 14, 2013 update: The Economist has some fun with an Erdoğan-as-Ottoman padishah on its cover.

Konstantin Kapidagli's 1803 portrait of Selim III - but with Erdoğan's face. |

June 19, 2013 update: Hugo Dixon provided details on the financial situation on June 17: In contrast to Erdoğan's bizarre claim that a "high-interest-rate lobby" of speculators wants to push interest rates up and suffocate the economy, speculators in fact have no incentive to jack up interest rates.

Foreign investors own $140 billion of domestic bonds and equities, according to Standard Bank. They will lose money if interest rates rise. The risk rather is that investors will pull out their money if they lose confidence. The U.S. Federal Reserve's indication that it may slow down its massive bond-purchasing programme has exacerbated that risk, as some of the money it has been pumping into U.S. bonds has seeped into emerging markets such as Turkey.

What's more, the Turkish miracle isn't quite as good as it seems. The economy grew only 2.6 percent last year, down from 8.5 percent the previous year – after the central bank had to hike interest rates because the economy was overheating and inflation reached 8.9 percent last year.

Turkey's biggest economic weakness is its current account deficit – a sign that consumption has been growing faster than is sustainable. The deficit did fall to 5.9 percent of GDP last year, after a 9.7 percent gap the previous year, as the economy slowed. But it is rising again this year. The April trade deficit was $10.3 billion, up from $6.6 billion last year.

Indeed, the selloff in Turkey's financial markets began a week or so before the police crackdown on protestors in Istanbul's Taksim Square on May 31. For example, two-year bond yields rose from 4.8 percent on May 17 to 6 percent at the end of the month; and the stock market fell 8 percent between May 22 and the end of the month. …

A particular weakness is that the current account deficit has been largely funded with hot money. The share accounted for by foreign direct investment – long-term money that can't easily run away – has been falling, according to Morgan Stanley. Meanwhile, the share made up by debt has been on the rise. …

the central bank has $130 billion of reserves, which it dipped into last week when it helped to stabilise the foreign exchange market. This war chest, though, is low compared to Turkey's external financing needs. What's more, the net reserves – after excluding foreign exchange deposited by the banking system – are only $46 billion, according to Standard Bank.

So the central bank couldn't hold the line if the "interest-rate lobby" really did run for the exits. In that case, Turkey would have to raise interest rates, which would damage growth. And then the economic miracle, which Erdoğan has presided over and which is one of the main sources of his popularity, might look like a conjuring trick.

July 1, 2013 update: "Will investors flood out of Turkey?" asks Elizabeth Stephens in the New Statesman. Her reply:

It really depends on who they are.

For the Gulf sheiks Turkey remains a safe investment haven and it is Arab money that has flooded into the country, fuelling a financial bubble and high inflation. These investors are unlikely to be concerned about the tactics Erdoğan employs to quash protests and will continue to view Turkey as a safe investment haven after the Arab Spring as they are wary of investing in Western countries because if unrest breaks out, their assets could be frozen.

Western investors have a different view - partly driven by concern over returns - and partly by the reputational risk that could arise from investments in Turkey if protests escalate and Erdoğan instigates another crackdown against them. The financial outlook is also worrying.