How should American voters concerned with Israel's welfare and security vote in the U.S. Congressional elections on Nov. 2?

This much is clear after almost two years of Democratic control over the executive and legislative branches of government: Democrats consistently support Israel and its government far less than do Republicans. Leaving Barack Obama aside for now (he's not on the ballot), let's focus on Congress and on voters.

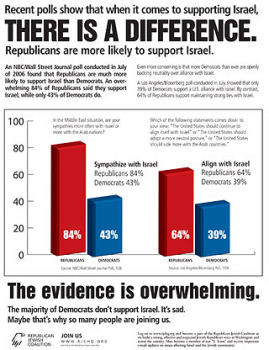

An ad by the Republican Jewish Coalition points out weaker Democratic support for Israel. |

In the same spirit, 54 House Democrats and not a single Republican signed a letter to Barack Obama a year later, in January 2010, asking him to "advocate for immediate improvements for Gaza in the following areas" and then listed ten ways to help Hamas, the Palestinian terrorist organization.

In dramatic contrast, 78 House Republicans wrote a "Dear Prime Minister Netanyahu" letter a few months later to express their "steadfast support" for him and Israel. The signatories were not just Republicans but members of the House Republican Study Committee, a conservative caucus.

So, count 54 Democrats for Hamas and 78 Republicans for Israel.

In the aftermath of the March 2010 crisis when Joe Biden went to Jerusalem, 333 members of the House of Representatives signed a letter to the secretary of state reaffirming the U.S.-Israel alliance. The 102 members who did not sign included 94 Democrats (including Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi) and 8 Republicans, a 12-to-1 ratio. Seventy-six senators signed a similar letter; the 24 who did not sign included 20 Democrats and 4 Republicans, a 5-to-1 ratio.

Voters: Public opinion explains these differences on Capitol Hill.

An April 2009 poll by Zogby International asked about U.S. policy: Ten percent of Obama voters and 60 percent of voters for Republican John McCain wanted the president to support Israel. Get tough with Israel? Eighty percent of Obama voters said yes and 73 percent of McCain voters said no. Conversely, 67 percent of Obama voters said yes and 79 percent of McCain voters said no to Washington engaging with Hamas. And 61 percent of Obama voters endorsed a Palestinian "right of return," while only 21 percent of McCain voters concurred.

Almost a year later, the same pollster asked American adults how best to deal with the Arab-Israeli conflict and found "a strong divide" on this question. Seventy-three percent of Democrats wanted the president to end the historic bond with Israel but treat Arabs and Israelis alike; only 24 percent of Republicans endorsed this shift.

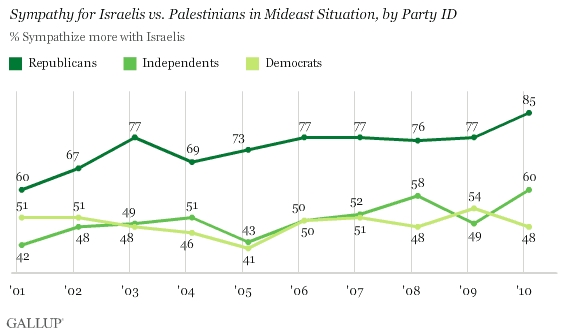

Gallup on "Sympathy for Israelis vs. Palestinians in Mideast Situation, by Party ID." |

A survey this month asked if a likely voter is "more likely or less likely to vote for a candidate whom you perceive as pro-Israel." Thirty-nine percent of Democrats and 69 percent of Republicans prefer the pro-Israel candidate. Turned around, 33 percent of Democrats and 14 percent of Republicans would be less likely to support a candidate because he is pro-Israel. Democrats are somewhat evenly split on Israel but Republicans favor it by a 5-to-1 ratio.

A consensus exists that the two parties are growing further apart over time. Pro-Israel, conservative Jeff Jacoby of the Boston Globe finds that "the old political consensus that brought Republicans and Democrats together in support of the Middle East's only flourishing democracy is breaking down." Anti-Israel, left-wing James Zogby of the Arab American Institute agrees, writing that "traditional U.S. policy toward the Israeli-Palestinian conflict does not have bipartisan backing." Thanks to changes in the Democratic party, Israel has become a partisan issue in American politics, an unwelcome development for it.

In late March 2010, during a nadir of U.S.-Israel relations, Janine Zacharia wrote in the Washington Post that some Israelis expect their prime minister to "search for ways to buy time until the midterm U.S. elections [of November 2010] in hopes that Obama would lose support and that more pro-Israel Republicans would be elected." That an Israeli leader is thought to stall for fewer Congressional Democrats confirms the changes outlined here. It also provides guidance for voters.

Mr. Pipes is director of the Middle East Forum and Taube distinguished visiting fellow at the Hoover Institution of Stanford University.

Oct. 19, 2010 update: For a more extensive compilation of figures on this topic, see my weblog entry, "Republicans and Democrats Look at the Arab-Israeli Conflict."

Nov. 9, 2010 update: In March 2010, the U.S. government expressed outrage when the Netanyahu government announced new housing starts in eastern Jerusalem; and now in November, it is doing likewise and for the same reason. But the Israeli response is quite different, explain Mark Landler and Ethan Bronner in the New York Times:

Analysts said Mr. Netanyahu's unyielding tone — a palpable contrast to his chagrined reaction after a similar housing dispute during a visit to Israel by Vice President Joseph R. Biden Jr. — testified to the altered political environment in the United States. The stinging Democratic defeat in the midterm elections, the analysts said, had emboldened Mr. Netanyahu to push back harder against the administration.

"He is dealing with a president who is politically weakened," said Daniel C. Kurtzer, a former American ambassador to Israel. "A lot of his friends in Washington are Republicans. He feels more comfortable with them, so he just feels that he's got a freer hand here."

Nov. 10, 2010 update: Alon Pinkas, a leftist former Israeli consul general in New York, notes the same pattern I do in an article titled "Undermining bipartisanship on Israel" but blames it on Netanyahu, calling his actions "a distinct break from the past 40 years, when Israel's strengthening ties with Washington were all a product of bipartisan support — regardless of who was in the White House or who controlled Congress." True, it is a break, but put the blame where it belongs, on the Democrats, not Netanyahu.