"Victory" has nearly dropped out of the minds and vocabularies of modern Westerners, replaced by compromise, mediation, and slogans such as "There is no military solution" and "War never solved anything." President Jacques Chirac of France declared in 2003 that "War is always the admission of defeat and is always the worst of solutions."

"Victory" has nearly dropped out of the minds and vocabularies of modern Westerners, replaced by compromise, mediation, and slogans such as "There is no military solution" and "War never solved anything." President Jacques Chirac of France declared in 2003 that "War is always the admission of defeat and is always the worst of solutions."

I beg to disagree. A bracing t-shirt counter-slogan explains why: "Except for ending slavery, Fascism, Nazism, Communism and Baathism, war has never solved anything." Those atrocities ended because the military forces supporting them were defeated or gave up without a fight. And wars end only through defeat and victory; if you don't win a war you lose it. Therefore, in today's world, the United States must achieve victory over radical Islam and Israeli over the Palestinians.

This emphasis on victory fits into a long line of military analysis. For example:

Thucydides, about 400 BCE: "Let us attack and subdue ... that we may ourselves live safely for the future."

Sun Tzu, about 350 BCE: "Let your great object be victory."

Aristotle, about 340 BCE: "Victory is the end of generalship."

Quintus Ennius, about 200 BCE: "The victor is not victorious if the vanquished does not consider himself so" ("Qui vincit non est victor nisi victus fatetur.")

Niccolò Machiavelli (paraphrased), 1513: "Enemies who cannot be won over must be crushed."

Raimondo Montecuccoli, 1670: "The objective in war is victory."

Montesquieu, 1748: "The object of war is victory."

HMS Victory. |

HMS Victory was Lord Nelson's flagship in his victory at the Battle of Trafalgar over the French and Spanish fleets on October 21, 1805.

Karl von Clausewitz, 1832: "War ... is an act of violence intended to compel our opponent to fulfill our will." "The aim of war should be the defeat of the enemy."

Karl von Clausewitz, author of "On War." |

Harold L. George, U.S. Army lieutenant general, 1934: "the object of war is now and always has been, the overcoming of the hostile will to resist. The defeat of the enemy's armed forces is not the object of war; the occupation of his territory is not the object of war. Each of these is merely a means to an end; and the end is overcoming his will to resist. When that will is broken, when that will disintegrates, then capitulation follows."

Winston Churchill, 1940: "You ask, what is our aim? I can answer in one word: It is victory, victory at all costs, victory in spite of terror, victory, however long and hard the road may be; for without victory, there is no survival."

Dwight D. Eisenhower, 1944: "In war there is no substitute for victory." (Also stated - and made famous - by Douglas MacArthur in 1951.)

From "The Yale Book of Quotations," edited by Fred R. Shapiro, p. 231.

- Douglas MacArthur, 1952: "It is fatal to enter any war without the will to win it."

Saul Alinsky, 1972: "People don't get opportunity or freedom or equality or dignity as an act of charity; they have to fight for it, force it out of the establishment. This liberal cliché about reconciliation of opposing forces is a load of crap. Reconciliation means just one thing: When one side gets enough power, then the other side gets reconciled to it. ... If you're too delicate to exert the necessary pressures on the power structure, then you might as well get out of the ball park."

Ronald Reagan, 1979, on his strategy for the Cold War: "We win, they lose."

Ronald Reagan, 1979, on his strategy for the Cold War: "We win, they lose."Ideals Publications Inc, publisher of Victory: Honoring the 50th Anniversary of the Allied Triumph in World War II (Nashville).

Uzi Landau, Israeli minister of national infrastructure, 2004: "When you're in a war you want to win the war."

James Mathis, U.S. marine general, ca. 2005: "No war is over until the enemy says it's over. We may think it over, we may declare it over, but in fact, the enemy gets a vote."

The Western drive for victory fundamentally changed with the coming of nuclear weapons. As Richard Pipes explained in 1977, "a group of civilian strategic theorists enunciated the principles of the mutual-deterrence theory which subsequently became the official U.S. strategic doctrine" in a 1946 book, The Absolute Weapon.

Modern strategy, in the opinion of its contributors, involved preventing wars rather than winning them, securing sufficiency in decisive weapons rather than superiority, and even ensuring the potential enemy's ability to strike back. Needless to elaborate, these principles ran contrary to all the tenets of traditional military theory, which had always called for superiority in forces and viewed the objective of war to be victory.

Here are occasional contemporary quotes on the topic of victory, or its absence:

Barack Obama, president of the United States, asked by an interviewer to define a U.S. victory in Afghanistan:

I'm always worried about using the word "victory" because, you know, it invokes this notion of Emperor Hirohito coming down and signing a surrender to [Douglas] MacArthur. ... when you have a non-state actor, a shadowy operation like al-Qaeda, our goal is to make sure they can't attack the United States. ... What that means is that they cannot set up permanent bases and train people from which to launch attacks. And we are confident that if we are assisting the Afghan people and improving their security situation, stabilizing their government, providing help on economic development so they have alternatives to the heroin trade that is now flourishing.

Japanese foreign minister Shigemitsu Mamoru signed his country's surrender on Sep. 2, 1945. |

Katie Paul of Newsweek reviews "Why Wars No Longer End with Winners and Losers." Excerpts:

Before 1945, there was something like a formula for how wars were fought and ended. When groups disagreed, usually over a piece of land, and failed to reconcile their differences amicably, they duked it out until one surrendered and the other carried off the prize. When they ended, wars had clear winners and losers.

Things have since changed.

how are wars won now? Increasingly, they're not. Instead, says Page Fortna, a political scientist at Columbia University who researches war outcomes, nearly half of all wars since World War II have ended indecisively. That trend between states started with the Cold War, and for civil wars it began when the Cold War ended. (By contrast, only half a percent of all wars fought between 1816 and 1946 ended without a victor, according to the Correlates of War, an academic project that codes war outcomes.)

Why?

"Because of changing norms about what is acceptable to gain through warfare, issues that were once resolved militarily are now often left unresolved," she says. "There are still cases when one side is clearly stronger militarily, but that often doesn't translate into political victory." ...

unconditional surrender is so rare nowadays—what, then, does it mean to win a war? And what happens in its place?

Looking at the Arab-Israeli conflict:

Israel has shown superior strength of arms on the battlefield at least eight times. ... But because of the distinction between military outcomes and political outcomes, the geography of Israel still looks roughly the same as it did after 1948.

That's because the conflict is fought as much today over public relations as it is on the battlefield. Both sides, for example, claimed victory after the 2009 war between Israel and Hamas. And although Israel clearly destroyed more targets and lost fewer lives, if Hamas doesn't admit defeat, who's to say it actually lost? ...

Militaries today refrain from pursuing the ruthless tactics associated with absolute war, mindful of CNN and cell-phone cameras.

Successful negotiations have negative implications:

Since the end of the Cold War, negotiated settlements have become the enlightened way to end civil wars: while 80 percent once ended with military victories, the split is now 40-40 (draws make up the rest). But El Salvador's success story may be the exception, not the rule. Negotiated settlements tend to break down, as they did in Sudan, where a series of peace agreements disintegrated into renewed war in 1983 and 2005. ...

Battlefield victories are hard to enforce:

Victories that end with a bang seem obvious enough to spot. But often, what seems like outright victory only leaves a discontented population (even if it's the minority) unwilling to accept defeat but smart enough not to reignite outright combat.

In Chechnya's case, Russia launched wars in 1994 and 1999 to respond to secession attempts by Chechen rebels. It's not hard to see who had the greater strength of arms; Russian forces utterly decimated the capital, Grozny, and resumed direct control of its government, while the rebels have accomplished only terror attacks and targeted killings. ...

Rather than surrender or continue fighting, the rebels simply resorted to wilier methods. In 2002, they stormed a Moscow theatre and began a hostage crisis that left 129 civilians dead. Others targeted an elementary school in Beslan, North Ossetia, in 2004—killing 344, more than half of them children. And so there's something like a standoff. On one side remains a scattered insurgency. On the other are routine crackdowns by Moscow's client. Still, this past April, Russia announced an end to its counterterrorism operations, effectively declaring Chechnya's separatist battles over. ...

"Victories since World War II are both less common and less clear, but they do still happen." Paul mentions Vietnam, Kuwait, and Sri Lanka. She quotes Harvard political scientist Monica Duffy Toft arguing that military victories produce a more durable peace than negotiated settlements. (Jan. 11, 2010)

Iran: The old ideas still prevail in the non-Western world, as Harold Rhodes indicates in his discussion of "The Sources of Iranian Negotiating Behavior":

In politics, Iranians negotiate only after defeating their enemies. During these negotiations, the victor magnanimously dictates to the vanquished how things will be conducted thereafter. Signaling a desire to talk before being victorious is, in Iranian eyes, a sign of weakness or lack of will to win.

(September 13, 2010)

John David Lewis, Bowling Green State University: His book, Nothing Less than Victory: Decisive Wars and the Lessons of History (Princeton University Press) establishes by looking at six wars that only through victory can a lasting peace be established. He notes the "astonishing" changes in U.S. doctrine after World War II:

The change in American military doctrine behind these developments occurred with astonishing speed; in 1939 American military planners still chose their objectives on the basis of the following understanding: "Decisive defeat in battle breaks the enemy's will to war and forces him to sue for peace which is the national aim." But U.S. military doctrine since World War II has progressively devalued victory as the object of war. "Victory alone as an aim of war cannot be justified, since in itself victory does not always assure the realization of national objectives," is the claim in a Korean War–era manual. The practical result has followed pitilessly: despite some hundred thousand dead, the United States has not achieved an unambiguous military victory since 1945.

This shift deserves careful study. In another passage, Lewis offers a useful corollary to Clausewitz' notion of the need to attack the enemy's center of gravity:

The "center" of a nation's strength, I maintain, is not a "center of gravity" as a point of balance, but rather the essential source of ideological and moral strength, which, if broken, makes it impossible to continue the war. A commander's most urgent task is to identify this central point for his enemy's overall war effort and to direct his forces against that center — be it economic, social, or military — with a view to collapsing the opponent's commitment to continue the war. To break the "will to fight" is to reverse not only the political decision to continue the war by inducing a decision to surrender, but also the commitment of the population to continue (or to restart) the war.

Lewis argues that, in each of the six examples he analyzes in his book, "the tide of war turned when one side tasted defeat and its will to continue, rather than stiffening, collapsed." (July 7, 2011)

J.M. Coetzee, 2013: "There is such a thing as defeat, and the Palestinians have been defeated. Bitter though such a fate may be, they must taste it, call it by its true name, swallow it. They must accept defeat, and accept it constructively. The alternative, unconstructive way is to go on nourishing revanchist dreams of a tomorrow when all wrongs, by some miracle, will be righted. For a constructive way of accepting defeat they might look to Germany post-1945."

Uzi Landau, Israeli politician: When Israeli military officials speak, "you don't want to hear things like 'quiet equals quiet.' You want them to speak in terms of victory." (July 7, 2014)

Roger Berkowitz of Bard College notes in "When The Hell That Is War Loses Its Power" that the Arab-Israeli conflict goes on because no one ever loses:

The tragedy that is the Middle East would, traditionally, have been solved by a war. One side would win, the other would lose. It is not predictable which side would prevail. The Israeli advantage in weapons of war would be met by the Palestinian advantage in unconventional warfare. But war would decide the issue once and for all and after its hellish baptism by blood, new lives would grow.

But war today is increasingly impossible, at least wars with clear victors and losers. War is being replaced by police-actions, patrols, terrors, and assassinations that go on without end. It is nearly inconceivable that Israel and Palestine would fight a war to the end in which one side was defeated—imagine the unthinkable horrors that defeating either side would require. Victory is impossible, just as it was inconceivable during the cold war that the United States and the Soviet Union would fight World War III. From such a war, there would be little hope of any life remaining.

And thus we are left with the condition of eternal war without end and mini-wars that corrupt political and peaceful institutions. In a world in which war has lost its power to settle disputes, we have ongoing wars that mobilize societies. The war on terror is a permanent part of our always-mobilized societies. We are left ... with the hell of war as a relatively permanent part of everyday life. Nowhere is that possibility more visible than in the Middle East.

A car window sticker available on eBay.

Comments: (1) I agree with the gist of this. (2) But wonder that Berkowitz finds it "not predictable" who might win and that he considers victory "nearly inconceivable" and "impossible" because of the "unthinkable horrors" it would entail. No, it would not be that hard for Israel to achieve. (July 19, 2014)

Brian Mast, candidate for (and then member of) Congress (with reference to ISIS): "The only way to guarantee peace is to make the enemy surrender." (March 2, 2016)

Binyamin Netanyahu carrying a copy of John David Lewis, "Nothing Less than Victory." |

Angelo M. Codevilla, probably America's greatest living strategist, points with precision to the moment when victory disappeared from the U.S. vocabulary of war. His opening paragraph in the Claremont Review of Books summarizes his thesis:

Progressivism's perversion of our ruling class's ideas about war and peace began at the turn of the 20th century. It prevailed in the winter of 1950-51 when this class, having committed the armed forces to war in Korea, decided to order them not to defeat an enemy that had already killed some 15,000 of their number, but rather to kill and die to "avoid a wider war," and to foster an international environment pleasing to itself and allied governments.

Since then, the U.S. government has won no wars. More important, it has not sought to win wars. Instead, our foreign policy establishment has spent some 100,000 American lives and trillions of dollars in Korea, Vietnam, Iraq, Afghanistan, and elsewhere in pursuit of world order, multilateralism, or collective security. It has cited as a badge of superior wisdom its trashing of Aristotle's notion that victory is war's natural objective.

Codevilla portrays Truman as a rube who "deferred to the men who had surrounded the great Roosevelt." Not surprisingly, he presents the firing of Douglas MacArthur (a general "who could imagine neither fighting a war for any purpose other than victory, nor refusing to employ whatever weapons would bring victory most directly"), as the key event in the fundamental shift from victory to advancing international peace and order.

The two books Codevilla reviews in "The Tipping Point" deal with MacArthur's life and his clash with Truman. One passage, while not directly relevant to the issue of victory, must be quoted for the memorable sense of the general:

MacArthur's immediate preoccupation as the U.S. Army's chief of staff from 1930 to 1935 was to save the officer corps from near extinction by a political system consumed by the Great Depression's stringencies.

In 1934, after Roosevelt had refused to rescind his cuts in the Army's budget, MacArthur confronted him: when "an American boy, lying in the mud with an enemy bayonet through his belly and an enemy foot on his dying throat, spat out his last curse, I wanted the name not to be MacArthur, but Roosevelt."

FDR shot back, "You must not talk that way to the President!" Having done just that, MacArthur said, "You have my resignation" and headed for the door. Sensing the political if not the moral threat, FDR stopped him. "Don't be foolish Douglas; you and the budget must get together on this."

(April 25, 2017)

Ron Chernow writes in his new book, Grant, about the ferocity of Gen. William Sherman's campaigns against the Confederacy in the U.S. Civil War:

Ron Chernow writes in his new book, Grant, about the ferocity of Gen. William Sherman's campaigns against the Confederacy in the U.S. Civil War:

Given the outsize casualties under [Gen. Ulysses] Grant, Republicans needed a major southern city to fall before the election to demonstrate genuine progress. By now Sherman preached a doctrine of total warfare that grew over more militant. By late 1863, his letters to Grant throbbed with a burning sense of vengeance as he planned to widen the war to engulf civilian society, obliterating the South's productive capacity. When Grant gave Sherman his marching orders in April 1864, he provided him with extraordinary autonomy in his impending campaign against Joseph Johnston's army and Atlanta. The brief orders allowed Sherman to fill in the blanks as he attacked Johnston in the mountainous terrain of northwest Georgia. From afar Grant followed Sherman with admiration, later contenting that his campaign toward Atlanta had been "managed with the consummate skill, the enemy being flanked out of one position after another all the way there."

As his men trooped south, Sherman took note of enemy resilience. "No amount of poverty or adversity seems to shake their faith; niggers gone, wealth and luxury gone, money worthless ... yet I see no sign of let up." Only violence on a massive scale, he believed, could subdue such a hardy and refractory breed. "I begin to regard the death and mangling of a couple thousand men as a small affair, a kind of morning dash," he wrote. "The worst of the war is not yet begun." Sherman wanted to implant in his men a fighting spirit that would alter the whole balance of the war. He also wished to inflict psychological damage on the southern people because the North was "not only fighting hostile armies but a hostile people, and must make old and young, rich and poor, feel the hard hand of war, as well as the organized armies." Better to bring the war to a speedy conclusion by hard fighting, he thought, than prolong the suffering of the conflict. ...

Aware of being the South's bête noire, Sherman hoped to take advantage of this terrifying image and foresaw the psychological effect a march would have in demoralizing the enemy. He wanted southerners to "feel the hard hand of war" and realize that, contrary to southern propaganda, the North was winning. To Grant, Sherman talked of visiting havoc on the Carolinas, boasting, "I can go on and smash South Carolina all to pieces." With his former love of southern culture, Sherman both feared and favored a policy of revenge. "The truth is, [my] whole army is burning with an insatiable desire to wreak vengeance upon South Carolina," he informed [Gen. Henry] Halleck. "I almost tremble at her fate but feel that she deserves all that seems in store for her."

(October 10, 2017)

A poster entitled "Peace Through Victory" by Thomas Nast from Harper's Weekly, Sep. 24, 1864. |

Victor Davis Hansen concurs:

From the Punic Wars (264–146 b.c.) and the Hundred Years War (1337–1453) to the Arab–Israeli wars (1947–) and the so-called War on Terror (2001–), some wars never seem to end. ... So, what prevents strategic resolution? Among many reasons, two throughout history stand out.

One, such bella interrupta involve belligerents who are roughly equally matched. Neither side had enough of a material or spiritual edge (or sometimes the desire) to defeat, humiliate, and dictate terms to the beaten enemy. ... In contrast, there was not another American Civil War, because after the invasions of Grant, Sherman, and Sheridan between 1864 and 1865, the Confederacy lost the ability to resist, and Union armies forced an unconditional surrender and a mandated reentry into the Union. ...

In the post-war nuclear age, America's enemies having roughly equal military power was never the reason that America failed to achieve victory in conventional wars. Rather, for a variety of reasons — political, cultural, social, economic — the U.S., at times, both wisely and foolishly, chose not to apply its full strength to pursue the unconditional surrender of its enemies. In other cases of never-ending wars, the two sides were clearly asymmetrical. One side easily could and should have won decisively and ended the conflict with a lasting resolution. Yet the apparently stronger side chose not to win, or for a variety of circumstances was prevented from victory.

At this point, he turns to the Arab-Israeli conflict:

Tiny Israel has had the power to vanquish its enemies in an existential war, but chose not to use its full military potential — given both internal and external pressures. Israel apparently concluded that the permanent occupations of the Sinai, Gaza, and borderlands of Lebanon, which would have provided permanent demilitarized ground corridors, would be too costly either in terms of policing and stabilizing hostile populations or too politically expensive in alienating key Western allies.

Nor did Israel think it could force a consensual government on the West Bank or change hearts and minds, as happened with the Israeli Arabs who do not regularly organize and fight Tel Aviv. Nor, in an age of missiles and rockets, did Israel yet have the technological ability to create absolutely safe skies or the global support to retaliate by air in Roman fashion.

The result was that Israel is forced into a chronic cycle of defeating regional enemies without the ability to end the perpetual willingness of the defeated to suffer tactical defeat, and then rearm and reequip during periods between wars, and then renew the conflict on supposedly better terms.

Returning to the United States:

Americans feel that the level of force and violence necessary to obliterate the Taliban and impose a lasting settlement is either too costly, or not worth any envisioned victory, or impossible in such absurd tribal landscapes, or would be deemed immoral and contrary to Western values. Therefore, as in most serial wars, the U.S. chooses to fight to prevent defeat rather than to achieve lasting victory. ... Western nations rarely deem an enemy so purely evil that it deserves the full force of Western might or that defeating it will be worth the potentially high cost. ...

The result is the present age of serial Punic conflict, perhaps intolerable to the psyche, but in amoral terms tolerable as long as casualties are kept to a minimum and defeat is redefined as acceptable strategic wisdom. In the past, such periods of enervating war have gone on for a century and more. Ultimately, they too end — and with consequences.

(November 21, 2017)

Feb. 26, 2019 update: "Army Warriors live and breathe victory" reads a Facebook recruitment advertisement for the U.S. Army.

May 20, 2019 update: Walter Russell Mead writes in "Palestinians Need to Get Real About Israel":

Palestinians today don't need a Nelson Mandela who can lead the struggle for equal political rights in one state. They need a Konrad Adenauer: a leader who can accept military defeat and painful territorial losses while building a prosperous future through reconciliation with the victors. As Adenauer's postwar West Germany showed, it is possible to recover from crushing defeats, but defeat must be accepted before it can be overcome. A new generation, instead of following its elders down the rabbit hole of eternally futile resistance, could instead work toward competent governance, and ultimately reconciliation and renewal.

Oct. 23, 2019 update: Trump's speech today about Syria was surreal because he claimed yesterday's Russian-Turkish agreement to shut out the United States as a triumph. I sometimes wonder if he and I inhabit the same universe.

At least there was robust talk about victory, though I wonder if the haplessness of the speech will cause this part to be discredited:

I am committed to pursuing a ... course ... that leads to victory for America. ... When we commit American troops to battle, we must do so only when a vital national interest is at stake, and when we have a clear objective, a plan for victory, and a path out of conflict. That's what we have to have. We need a plan of victory. We will only win. Our whole basis has to be the right plan, and then we will only win. Nobody can beat us. Nobody can beat us.

Aug. 24, 2021 update: Mike Duncan writes, referring to the 1781 Battle of Yorktown in Hero of Two Worlds The Marquis de Lafayette in the Age of Revolution:

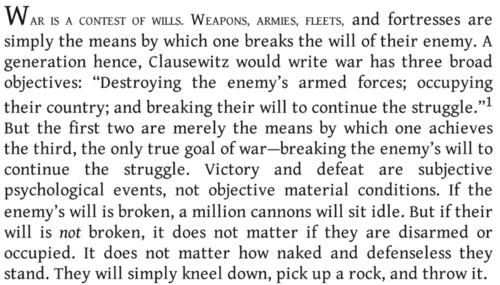

War is a contest of wills. Weapons, armies, fleets, and fortresses are simply the means by which one breaks the will of their enemy. A generation hence, Clausewitz would write, "War has three broad objectives: destroying your enemy's armed forces, occupying their country, and breaking their will to continue the struggle." But the first two are merely the means by which one achieves the third, the only true goal of war – breaking the enemy's will continue the struggle. Victory and defeat are subjective psychological events, not objective material conditions. If the enemy's will is broken, a million cannons will sit idle. But if their will is not broken, it does not matter if they are disarmed or occupied, it does not matter how naked and defenseless they stand. They will simply kneel down, pick up a rock and throw it.

May 1, 2022 update: Has Putin's invasion of Ukraine resurrected the idea of victory for Westerners? Nancy Pelosi, speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives, stated that "America stands with Ukraine until victory is won."

May 23, 2022 update: Anne Applebaum offers a bracing goal of victory and defeat in Ukraine:

our goal, our endgame, should be defeat. In fact, the only solution that offers some hope of long-term stability in Europe is rapid defeat, or even, to borrow Macron's phrase, humiliation. In truth, the Russian president not only has to stop fighting the war; he has to conclude that the war was a terrible mistake, one that can never be repeated. More to the point, the people around him—leaders of the army, the security services, the business community—have to conclude exactly the same thing. The Russian public must eventually come to agree too. ...

Military loss could create a real opening for national self-examination or for a major change, as it so often has done in Russia's past. Only failure can persuade the Russians themselves to question the sense and purpose of a colonial ideology that has repeatedly impoverished and ruined their own economy and society, as well as those of their neighbors, for decades. Yet another frozen conflict, yet another temporary holding pattern, yet another face-saving compromise will not end the pattern of Russian aggression or bring permanent peace.

May 26, 2022 update: A New York Times article by all of David E. Sanger, Eric Schmitt, Steven Erlanger, Julian Barnes, and Helene Cooper titled "The How Does It End? Fissures Emerge Over What Constitutes Victory in Ukraine" explores the topic of victory.

In recent days, presidents and prime ministers as well as the Democratic and Republican Party leaders in the United States have called for victory in Ukraine. But just beneath the surface are real divisions about what that would look like — and whether "victory" has the same definition in the United States, in Europe and, perhaps most importantly, in Ukraine. ...

At their heart lies a fundamental debate about whether the three-decade-long project to integrate Russia should end. At a moment when the U.S. refers to Russia as a pariah state that needs to be cut off from the world economy, others, largely in Europe, are warning of the dangers of isolating and humiliating Mr. Putin.

That argument is playing out as American ambitions expand. What began as an effort to make sure Russia did not have an easy victory over Ukraine shifted as soon as the Russian military began to make error after error, failing to take Kyiv. The administration now sees a chance to punish Russian aggression, weaken Mr. Putin, shore up NATO and the trans-Atlantic alliance and send a message to China, too. Along the way, it wants to prove that aggression is not rewarded with territorial gains. ...

Differing objectives, of course, make it all the more difficult to define what victory — or even a muddled peace — would look like.

June 3, 2022 update: Ukraine's president, Volodymyr Zelensky, declared "Victory will be ours!"

June 17, 2022 update: Ukraine's foreign minister, Dmytro Kuleba, calls for "a complete and total Ukrainian victory" over Russia.

Sep. 11, 2022 update: Mariia Mezentseva, a Ukrainian MP representing the city center of Kharkiv: "We don't need peace ... we need a victory" (at 7:44 in "Russia's 'rigid' forces collapse to 'audacious lightning' Ukraine counteroffensive" on UK Channel 4).

Oct. 26, 2022 update: U.S. Rep. Pramila Jayapal (a left-wing Democrat): "Every war ends with diplomacy, and this one will too after Ukrainian victory."

Oct. 7, 2023 update: The Hamas massacre of Israeli resident civilians has prompted an immediate and vehement adoption of victory as Israel's goal. I trace this in three weblog entries started today and to be updated: calls for the destruction of Hamas, general calls for victory, and calls by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu for victory.

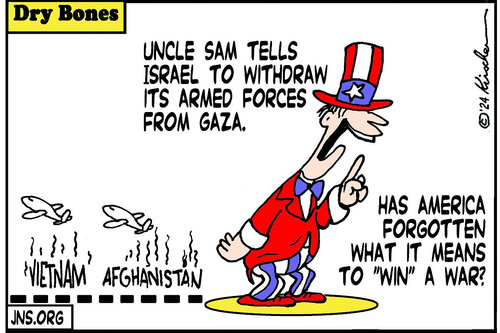

Jan. 17, 2024 update: The U.S. government does not want an Israel Victory. Dry Bones notes that this fits a pattern.

Jan. 18, 2024 update: Not only has Netanyahu publicly mentioned victory (by my surely incomplete count) in 27 statements in slightly over 100 days of war with Hamas, but he today referred 15 times to victory in the course of a 700-word address.

Apr. 10, 2024 update: Matt Pottinger and Mike Gallagher have adopted the victory theme in their Foreign Affairs article, "No Substitute for Victory: America's Competition With China Must Be Won, Not Managed."

May 3, 2024 update: In a rare instance of defeat and victory, Armenia has given up in its fight with Azerbaijan.

Dec. 5, 2024 update: Elliot Ackerman explains why Americans need to "Bring Back the War Department" in the Atlantic:

The Revolutionary War, the Civil War, and the First and Second World Wars were all fought and won by the War Department. Before 1947, when we had a War Department, Americans were able to boast that they had never lost a war. When the United States fought fewer major wars, its uninterrupted string of victories was a point of national pride. Since the creation of the Defense Department, the U.S. has never won a major war. Muddled outcomes such as those in Korea and Iraq are the closest thing it might claim to success.

A philosophy of defense has proved ineffective (if not disastrous) when compared with the more focused philosophy of war. Perhaps the War Department was less likely to fight wars, because its name made the department's purpose more difficult to sugarcoat and obfuscate. A war department speaks in terms of victory and defeat. George Washington, Abraham Lincoln, and Franklin D. Roosevelt never spoke of exit strategies, nor did generals such as Ulysses S. Grant, John Pershing, and Dwight D. Eisenhower wring their hands about "boots on the ground." If you want a clear strategy for winning wars, don't play a semantic game with the name of the department that's charged with the strategy's execution. Call things what they are. The mandate of a war department is right there in its name.

June 22, 2025 update: Pope Leo XIV has declared that "War does not solve problems; on the contrary, it amplifies them and inflicts deep wounds on the history of peoples, which take generations to heal. No armed victory can compensate for the pain of mothers, the fear of children, or stolen futures."