What is conservatism?

Before reading an article with this title by Ofir Haivry and Yoram Hazony in a recent issue of American Affairs, I would have replied individual liberty, small government, and a robust foreign policy. Their article taught me a completely different and much deeper understanding.

A title page of Fortescue's "In Praise of the Laws of England" (c. 1470). |

They advocated an outlook that respects tradition while intelligently adapting it to new circumstances; Haivry and Hazony call this historical empiricism. Conservatives esteem what preceding generations have worked out – especially, the English Constitution and the Hebrew Bible. They see England's unique development of freedom as the happy result of such singular breakthroughs as the Magna Carta (1215) and the Petition of Right (1628).

Caution is the conservatives' by-word: Look to the nation and religion for guidance; make sure to limit executive power and maintain individual freedoms. Judges – respect the original intent of documents. Politicians – if marriage has everywhere and always meant a union of man and woman, be very careful about fundamentally changing it. Governments – ensure that immigrants assimilate to the host culture.

Liberals, in contrast, are rationalists because they believe in each person's unlimited capacity to figure things out on his own. Tradition hardly counts: "Rather than arguing from the historical experience of nations, they set out by asserting general axioms that they believe to be true of all human beings, and that they suppose will be accepted by all human beings examining them with their native rational abilities."

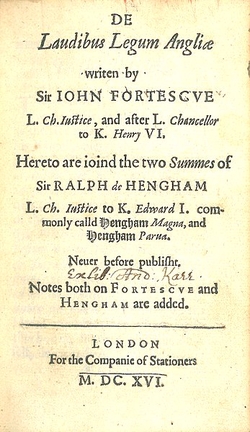

A title page of Locke's "Two Treatises of Government" (1689). |

The danger here, of course, is that individual humans have some strange and blinkered ideas. Liberalism enfranchises ideas far removed from the sobriety of the English Constitution, starting with the French Revolution and ending with the totalitarianisms of our time. Proclaimed universal laws can justify any sins once unmoored from accumulated wisdom and experience.

Conservatives and liberals have battled for three hundred years in the United Kingdom. Conservatives can point to the monarchy and the common law still standing as their accomplishments; liberals can point to uncontrolled immigration and at least 85 functioning Sharia courts.

A similar American debate exists. Conservatives included Alexander Hamilton, George Washington, and John Adams; liberals included Thomas Jefferson, Thomas Paine, and Andrew Jackson. Each side had its triumphs. The Declaration of Independence (1776) is a liberal document that holds various "truths to be self-evident," namely "that all men are created equal [and] that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights." The U.S. Constitution (1787) makes no mention of universal truths; rather, it translates key features of the English constitution for American use.

A liberal American yard sign: "Immigrants are a blessing, not a burden." |

The two sides are evenly matched in American politics, with power regularly shifting back and forth. But in education and culture, liberalism dominates. In schools, for example, liberals teach liberalism and conservatives are nearly absent. This liberal hegemony means conservatives are routinely castigated as "illiberal" and therefore morally inferior; thus did a recent Atlantic article ask, "Is American conservatism inherently bigoted?"

It also means, as Haivry writes me, that "while hundreds of prominent universities and institutes are devoted to examining the liberal tradition, none are dedicated to studying and developing the principles of Anglo-American conservatism. However, a few colleagues and I are trying to restore this great tradition and we seek support to set up an institution devoted to this goal." May their project prosper.

Mr. Pipes (DanielPipes.org, @DanielPipes) taught Western intellectual history at the University of Chicago. © 2018 by Daniel Pipes. All rights reserved.

July 31, 2018 addenda:

(1) This distinction goes far to explain why the less educated tend to be conservatives and the more educated tend to be liberals; the former are less likely to think themselves competent to think issues through on their own.

(2) I attended Robert Nozick's philosophy class when in college and, at his direction, read Friedrich Hayek's The Constitution of Liberty, which made a great impression on me. In particular, I was swayed by Hayek's essay, "Why I Am Not a Conservative." For close to 50 years, it caused me to assume I am a (classical) liberal. No more.

(3) The excellent college course I took in 1968-69 on "The History of Political Thought," taught by Judith Shklar and Michael Walzer, made no mention of this conservative history. See the reading list for what we did cover. Thus, I call it hidden.

(4) Before understanding that liberalism is defined by a belief in reason and the ability of each person capably to use reason, I had thought the essence of liberalism lay in other directions: there ought to be a law; fairness over freedom; co-option over confrontation; and expand entitlements.

(5) One of the most striking points Haivry and Hazony make concerns the weakness of the assumptions behind Locke's Second Treatise of Government. He

begins with a series of axioms that are without any evident connection to what can be known from the historical and empirical study of the state. Among other things, Locke asserts that, (1) prior to the establishment of government, men exist in a "state of nature," in which (2) "all men are naturally in a state of perfect freedom," as well as in (3) a "state of perfect equality, where naturally there is no superiority or jurisdiction of one over another." Moreover, (4) this state of nature "has a law of nature to govern it"; and (5) this law of nature is, as it happens, nothing other than human "reason" itself, which "teaches all mankind, who will but consult it." It is this universal reason, the same among all mankind, that leads them to (6) terminate the state of nature, "agreeing together mutually to enter into . . . one body politic" by an act of free consent. From these six axioms, Locke then proceeds to deduce the proper character of the political order for all nations on earth.

John Locke (1632-1704).

Three important things should be noticed about this set of axioms. The first is that the elements of Locke's political theory are not known from experience. ... The second thing to notice is that there is no reason to think that any of Locke's axioms are in fact true. ... Third, Locke's theory not only dispenses with the historical and empirical basis for the state, it also implies that such inquiries are, if not entirely unnecessary, then of secondary importance.

Comments: (a) How shocking to realize that the founding document of liberalism was based on pure fantasy. (b) In other words, this political philosophy had faulty premises from the very start. (c) Things did not get better over the next 329 years.

(6) Heather Mac Donald quotes Erin Palmer and Sabriya Rosemund of UC Berkeley in a January 2018 webinar for STEM teachers explaining that a primary goal of their introductory chemistry course is to disrupt the "racialized and gendered construct of scientific brilliance," which defines "good science" as getting all the right answers. The course maintains instead that "all students are scientifically brilliant." Comment: In addition to the absurdity of their goal, note the liberal assumption behind the statement, "all students are scientifically brilliant."

(7) Russell Kirk devised "Ten Conservative Principles," the third of which points to the inherent modesty of the conservative outlook – something no self-proclaimed genius would accept:

Conservatives sense that modern people are dwarfs on the shoulders of giants, able to see farther than their ancestors only because of the great stature of those who have preceded us in time. Therefore conservatives very often emphasize the importance of prescription—that is, of things established by immemorial usage, so that the mind of man runneth not to the contrary. There exist rights of which the chief sanction is their antiquity—including rights to property, often. Similarly, our morals are prescriptive in great part. Conservatives argue that we are unlikely, we moderns, to make any brave new discoveries in morals or politics or taste. It is perilous to weigh every passing issue on the basis of private judgment and private rationality. The individual is foolish, but the species is wise, Burke declared. In politics we do well to abide by precedent and precept and even prejudice, for the great mysterious incorporation of the human race has acquired a prescriptive wisdom far greater than any man's petty private rationality.

(8) Spirituality is an inherently liberal undertaking, for it assumes that experience (as embodied in religious institutions) has little value compared to each individual's personal quest.

Aug. 1, 2018 update: Rick Shenkman of the History News Network reminds me of the immortal summary of conservatism, pronounced by John Dickinson at the Constitutional Convention of 1787 in Philadelphia: "Experience must be our only guide. Reason may mislead us."

Aug. 1, 2018 update: Rick Shenkman of the History News Network reminds me of the immortal summary of conservatism, pronounced by John Dickinson at the Constitutional Convention of 1787 in Philadelphia: "Experience must be our only guide. Reason may mislead us."

Aug. 28, 2018 update: I build on this argument today in the Wall Street Journal at "Venezuela's Tyranny of Bad Ideas."

Sep. 1, 2018 update: In his new book, The Virtue of Nationalism, Hazony (on pp. 76-77) compares Locke's false but pretty tale of the state of nature to the stories parents tell their children about the stork bringing them into the world. But unlike the stork story, he maintains, which children quickly enough realize is false, the state of nature one continues to influence students into adulthood and into positions of authority.

Oct. 18, 2018 update: I draw some pessimistic conclusions for conservatism today at "Why Do You American Conservatives Keep Losing?"

Dec. 7, 2020 update: Mark Melcher and Stephen Soukup of The Political Forum summarize Western history since the Enlightenment

as a series of attempts to create a new moral code to impose on the universe in the wake of the intentional destruction of the pre-modern, pre-Enlightenment code that had provided moral guidance for some 2,000 years prior. These attempts inevitably fail, however, because the moral ideas they favor are based on capricious principles and the subjective notion of "reason," loosely defined, and because their initiators know precious little about morality in the first place.

Feb. 23, 2022 update: Stephen Soukup goes into detail about the philosophy of liberalism in education in his book, out today, The Dictatorship of Woke Capital: How Political Correctness Captured Big Business. One excerpt, about the American John Dewey:

Feb. 23, 2022 update: Stephen Soukup goes into detail about the philosophy of liberalism in education in his book, out today, The Dictatorship of Woke Capital: How Political Correctness Captured Big Business. One excerpt, about the American John Dewey:

Like Mill and Kant and Hume and the rest who came before him, Dewey disdained the idea of an existing body of acquired human social and moral knowledge that could and should be passed down from generation to generation in the form of custom and tradition. He believed that knowledge was not something that could be learned but something every individual student had to discover for himself. Dewey was dogmatic about this. He denigrated the traditional practice of focusing on teaching such subjects as reading, writing, mathematics, and history, and promoted the teaching of social and "thinking" skills instead. This, he thought, would be the salvation of mankind, learning to think without preconceptions.

Note especially: "knowledge was not something that could be learned but something every individual student had to discover for himself."

May 1, 2022 update: Hazony on his own has expanded the article discussed above into a 445-page book, Conservatism: A Rediscovery (Regnery Gateway).

May 1, 2022 update: Hazony on his own has expanded the article discussed above into a 445-page book, Conservatism: A Rediscovery (Regnery Gateway).