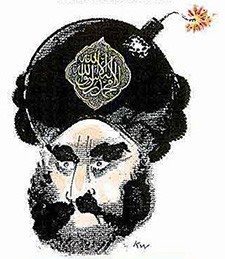

This cartoon of Muhammad by Kurt Westergaard, published on September 30, 2005, along with eleven others, garnered the most attention and anger. |

This incident points to the Islamists' mixed success in curbing Western freedom of speech about Muhammad – think of Salman Rushdie's Satanic Verses or the Deutsche Oper's production of Mozart's Idomeneo. If threats of violence sometimes do work, they as often provoke, anger, and inspire resistance. A polite demarche can achieve more. Illustrating this, note two parallel efforts, dating from 1955 and 1997, to remove nearly-identical American courthouse sculptures of Muhammad.

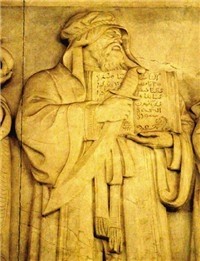

In 1997, the Council on American-Islamic Relations demanded that part of a 1930s frieze in the main chamber of the U.S. Supreme Court building in Washington, D.C. be sandblasted into oblivion, on the grounds that Islam prohibits representations of its prophet. The seven-foot high marble relief by Adolph Weinman depicts Muhammad as one of 18 historic lawgivers. His left hand holds the Koran in book form (a jarring historical inaccuracy from the Muslim point of view) and his right holds a sword.

The Supreme Court frieze depiction of Muhammad. Official court information points out that "The figure above is a well-intentioned attempt by the sculptor, Adolph Weinman, to honor Muhammad and it bears no resemblance to Muhammad. Muslims generally have a strong aversion to sculptured or pictured representations of their Prophet." |

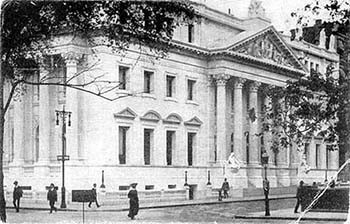

In contrast, back in 1955, a campaign to censor a representation of Muhammad in another American court building did succeed. That would be the New York City-based courthouse of the Appellate Division, First Department of the New York State Supreme Court. Built in 1902, it featured on its roof balustrade an eight-foot marble statue of "Mohammed" by Charles Albert Lopez as one of ten historic lawgivers. This Muhammad statue also held a Koran in his left hand and a scimitar in the right.

Though visible from the street, the identities of the lawgivers high atop the building were difficult to discern. Only with a general overhaul of the building in February 1953, including its statues, did the public become aware of their identities. The Egyptian, Indonesian, and Pakistani ambassadors to the United Nations responded by asking the U.S. Department of State to use its influence to have the Muhammad statue not renovated but removed.

Characteristically, the State Department dispatched two employees to convince New York City's public works commissioner, Frederick H. Zurmuhlen, to accommodate the ambassadors. The court, Chief Clerk George T. Campbell, reported, "also got a number of letters from Mohammedans about that time, all asking the court to get rid of the statue." All seven appellate justices recommended to Zurmuhlen that he take down the statue.

Even though, as Time magazine put it, "the danger that any large number of New Yorkers would take to worshiping the statue was, admittedly, minimal," the ambassadors got their way. Zurmuhlen had the offending statue carted off to a storehouse in Newark, New Jersey. As Zurmuhlen figured out what to do with it, the Times reported in 1955, the statue "has lain on its back in a crate for several months." Its ultimate disposition is unknown.

|

|

Top left: The courthouse of the Appellate Division, First Department of the New York State Supreme Court, at Madison Avenue and 25th Street, New York City, photographed before 1955 from the southwest. Note the presence of a statue at the far right (east) of the building. Bottom left: The same courthouse, post-1955. Note the missing statue at the far right. The Muhammad statue had been at the westerly end of the 25th Street side but the other statues on that side were moved one spot to the west in 1955, so that the empty plinth is now at the easterly end. Right: The New York Muhammad statue, described by the New York Times showing the prophet "of average height, but broad-shouldered, with thick, powerful hands. Under his turban, his brows are prominent and frowning. A long, heavy beard flows over his robe. In his left hand, he holds a book, symbolizing the new religion he founded, and in his right, a scimitar, connoting the Moslem conquest." |

|

Then, rather than replace the empty pedestal on the court building roof, Zurmuhlen had the nine remaining statues shifted around to disguise the empty space, with Zoroaster replacing Muhammad at the westerly corner spot. Over a half-century later, that is where matters remain at the courthouse.

The empty pedestal, where Muhammad stands no more. |

This conclusion confirms my more general point – and the premise of the Islamist Watch project – that Islamists working quietly within the system achieve more than ferocity and bellicosity. Ultimately, soft Islamism presents dangers as great as does violent Islamism.

Mr. Pipes, director of the Middle East Forum, is suspending his column for several weeks.

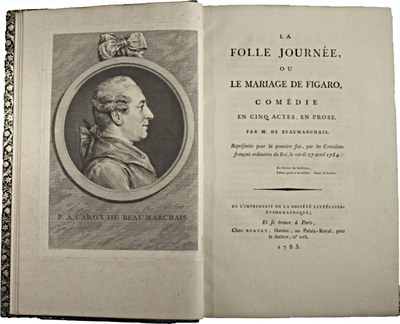

Feb. 28, 2008 addenda: (1) Even in the heyday of European power, there remained an awareness of Muslim sensitivity about Muhammad. French playwrite Beaumarchais caught this a speeh delieverd by the title character in his 1785 play, Le Mariage de Figaro (scene 5, act 3):

Auteur espagnol, je crois pouvoir y fronder Mahomet sans scrupule : à l'instant un envoyé... de je ne sais où se plaint que j'offense dans mes vers la Sublime-Porte, la Perse, une partie de la presqu'île de l'Inde, toute l'Egypte, les royaumes de Barca, de Tripoli, de Tunis, d'Alger et de Maroc : et voilà ma comédie flambée, pour plaire aux princes mahométans, dont pas un, je crois, ne sait lire, et qui nous meurtrissent l'omoplate, en nous disant : chiens de chrétiens.

Being a Spanish author, I thought I had the ability to mock Muhammad without concern. [But when I did,] an envoy ... from who knows where, immediately complained that my verses offended the Ottoman imperial court, Persia, part of India, all of Egypt, and the kingdoms of Benghazi, Tripoli, Tunis, Algiers, and Morocco. And so my comedy was torched to please the Muslim princes who call us "Christian dogs," ...although none of them – to my knowledge – knows how to read.

(2) A reader has informed me about a February 12, 2006, New York Times article, "Images of Muhammad, Gone for Good," in which author John Kifner tells about an instance of the newspaper showing a picture of the Muslim prophet in 1974, the 1977 movie Mohammad, Messenger of God, and finally the statue atop the appellate court building. About the disposition of the statue, Kifner reports it "was lowered by block and tackle, wrapped in excelsior and trucked off to a stone company in Newark. In the last reported sighting — in 1983 — the statue was lying on its side in a stand of tall grass somewhere in New Jersey."

(3) And why are there no Islamist calls for the removal of the Muhammad statue in Riverside Church in New York City, the tallest and one of the largest churches in the United States? The Muslim prophet is celebrated there along with Confucius, Moses, Hegel, Dante, and even Darwin.

The front panel of Sound Vision's brochure.

Nov. 2, 2011 update: Curiously, in light of CAIR's opposition to the Supreme Court's frieze of Muhammad, the Chicago-based Sound Vision Foundation celebrates the frieze in a brochure titled Prophet Muhammad Honored by U.S. Supreme Court as One of the Greatest Lawgivers of the World in 1935.

As the United States Supreme Court judges sit in their chamber, to their right, front, and the left sides are friezes depicting the 18 greatest lawgivers of the world. The second frieze to the right features a person holding a copy of the Quran, the Islamic holy book. It is intended to recognize Prophet Muhammad as one of the greatest lawgivers in the world, along with Moses, Solomon, Confucius, and Hammurabi, and others.

This switch in tactics results from the successful effort, led by the Center for Security Policy's American Law for American Courts initiative, to ban the Shari'a from U.S. courtrooms. The brochure continues:

While the learned people in our country knew of the contribution of Prophet Muhammad, our neighbors today given regular doses of misinformation about the Prophet and Sharia, the path of the Prophet, more commonly described as Islamic law.

Sound Vision then soars into flights of fancy about the biography of Muhammad, applying twenty-first-century mores to a seventh-century figure; note especially the bizarre and inaccurate references to "a mass peace movement" and "not more than six days."

Prophet Muhammad envisioned a just and peaceful society. With a mass peace movement, he achieved this goal during his life. He hated war and always preferred a peace treaty with his opponents, even if it was not favorable to his and his followers' interests. He established his first peace sanctuary in the city of Madinah without any war whatsoever. While he did fight to defend that peace sanctuary, it is critical to note that the total time of actual fighting defending his people was not more than six days in his life of 63 years. He struggled to secure a peace that ensured justice and liberation for all people, especially for those most marginalized and oppressed.

Comment: Islamists will say absolutely anything to advance their cause.

Jan. 10, 2015 update: In a curious article, "A Statue of Muhammad, Taken Down Years Ago," David W. Dunlap returns to the topic of the Muhammad statue in the New York Times, expressing his great relief that it was taken down from the Appellate Division Courthouse sixty years earlier. Two points from the dhimmi article:

1. Noting that the statue was last seen in 1983, "lying on its side in a stand of tall grass somewhere in New Jersey," Dunlap adds: "If the statue is still out there, however, now would not seem to be the moment to uncover it."

2. Noting that for Muslims, "depictions of the prophet are an affront," his article includes this statement in parentheses: "For [this] reason, The New York Times has chosen not to publish photographs of the statue with this article."